Matters of Debate

Class examines bioethics issues

Ann Borden

What if scientists could create a real, live Neanderthal person, using knowledge of a genome sequenced from prehistoric DNA?

That might seem like something from a Michael Crichton novel, but there is evidence that it's closer than you might think. That's why it was the first test problem put to students in a new, experimental course on bioethics—specifically, what Roberta Berry, an associate professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology, calls "ethically fractious problems."

Funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), the course brings together students from four Atlanta institutions—Emory, Georgia Tech, Georgia State University College of Law, and Morehouse School of Medicine—to study bioethical questions from cross-disciplinary perspectives. Berry, director of Georgia Tech's Law, Science, and Technology Program and the principal investigator for the project, conceived of the course to address emerging problems that meet five criteria: they are novel, complex, ethically fraught, divisive, and unavoidably of public concern.

"The point of the grant proposal is that these problems will keep coming up, and we need to find ways to deal with them," Berry says. "What caught the interest of the NSF was the idea of future scientists and engineers developing a particular set of skills necessary to deal with these issues at a policy level. The NSF also found the diverse mix of students very promising."

The students are placed on teams of five to six members that deliberately mix the different institutions and disciplines, with representatives from the biosciences, public policy, law, engineering, and even the humanities. There are no textbooks or assigned readings; rather, the teams are given a series of three problems and set loose (guided by a faculty facilitator) to develop policy recommendations, which they ultimately present to invited stakeholders and policymakers including scientists and engineers, patent attorneys, law professors, judges, legislators, and legislative staffers.

"This is an extraordinarily novel way to do interdisciplinary work," says Kathy Kinlaw, associate director of Emory's Center for Ethics and the Emory principal investigator and a facilitator for the course. "The students have to work at representing their own disciplinary expertise in a way that can be heard. It has been interesting to watch them communicate to each other, then formulate how they will communicate their findings to an educated public in order to impact the public policy process. It's a fascinating way to learn from a pedagogical perspective and much truer to the way they will work in the realms they are moving into."

Tara Wabbersen 12PhD is a fourth-year student in Emory's Graduate Division of Biomedical and Biological Sciences, where she works in cell and developmental biology. Her program requires an initial two-day bioethics course and additional classes once a month, but she says she was drawn to the depth offered by the NSF course.

"I've always been interested in bioethics, and I wanted a taste of what it's like to work with the bigger issues," she says. "I was also interested because, as a scientist, it's good to get perspective from nonscientists. It's easy to lose sight of that broader view."

Faced with the first question of the course, Wabbersen says it was fairly easy for her team to come up with the answer: no, scientists should not create a Neanderthal man. The challenge, though, was explaining why. "There were too many big questions," she says. "Would it be defined as a person? Would there be social and class issues? The law student wanted to know what its rights would be."

The NSF course was taught for the first time last year, and Sarah Cork 11PhD, a graduate student in neuroscience at Emory, jumped at the chance to take it. "I'm planning to go to law school, so I was very interested in the intersection of science and law and the ethical issues that arise," she says.

For her team's final problem, they were asked to determine whether a universal DNA database should be created that extends to all citizens, not just those with a criminal record. Initially, the team was divided on the issue, with the minority members objecting to the formation of the database—which made for some interesting and at times tense discussion, Cork says. Ultimately, they did recommend in favor of the database, although with a range of qualifications and restrictions.

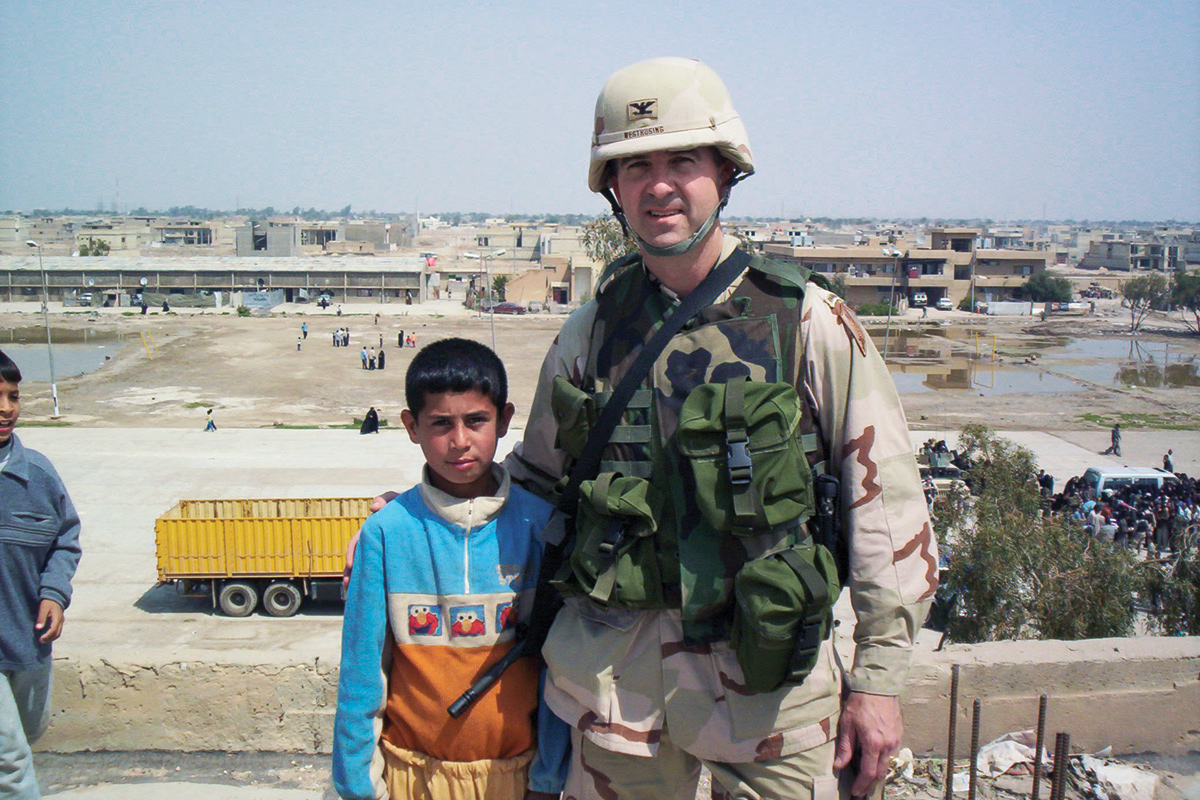

Surinder Chadha Jimenez's team supports development of a new cellular system to treat type I diabetes.

Ann Borden

This year's teams were assigned final problems with a focus on synthetic biology, so their work resonated with many of the key issues discussed by the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues, which met at Emory in November. Just days later, the two teams met in the Center for Ethics to deliver practice presentations to advisory council members.

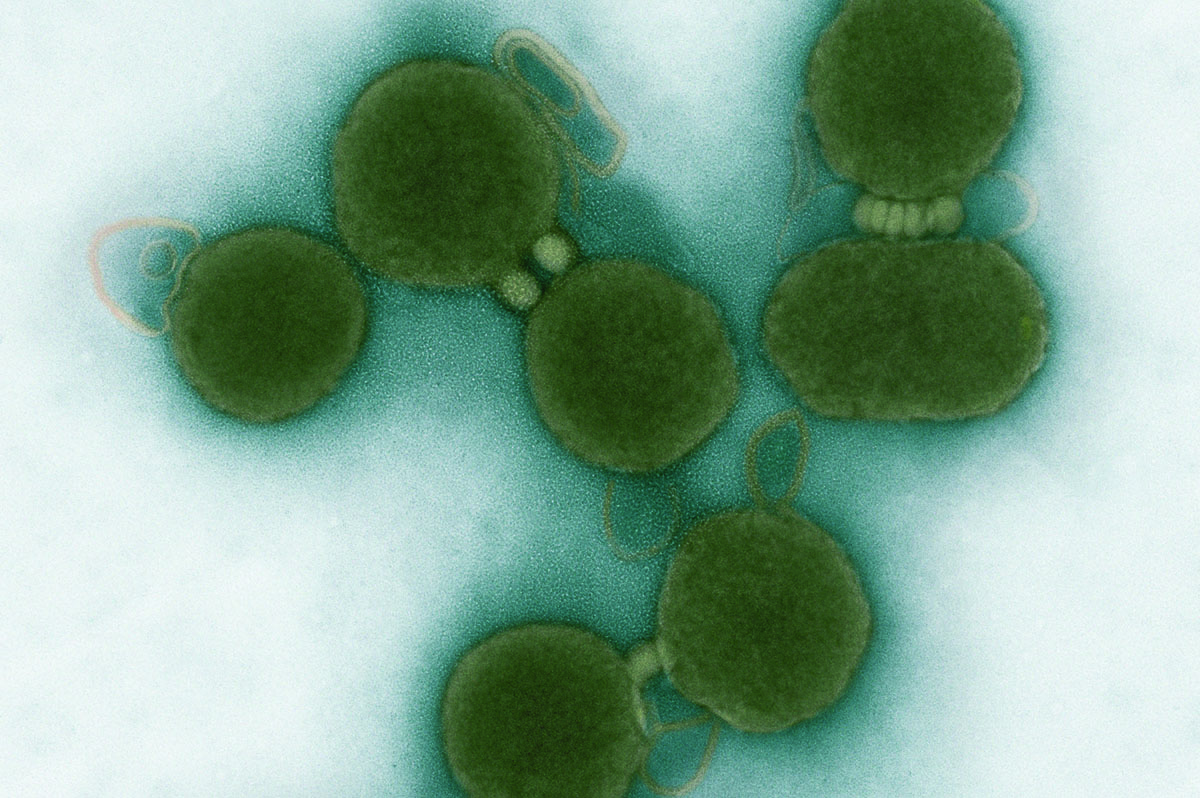

One team analyzed the potential impact of cultivating emergent behaviors of differentiating cells, basically the production of biological "machines" through steering the differentiation of interacting stem cells. The second team worked on a real-life project that is actually in development, led by a Harvard researcher—the creation of a cellular system designed to detect glucose levels in the blood and then instruct other systems to produce and secrete insulin, to be used in treating type I diabetes patients.

Both teams drew on the highly controversial use of human embryonic stem cells to illustrate their points, noting the ongoing debate over the definition of life and when it begins. They covered religious and ethical implications, the need for balance between private innovation and public interest, the possibility for dual use if the advances fall into the wrong hands, and the importance of public perception in the success of new biological technologies. Ultimately, the teams found that researchers in these areas should be encouraged to proceed—but with caution, and overseen by regulatory agencies and clear, restrictive policies. Still, the potential for health benefits far outweighs the risks, the teams said.

Melissa Creary 14PhD, who is studying public health, ethics, and history in the Institute for Liberal Arts, has worked in the Division of Blood Disorders at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the past six years. "In my work, ethics comes up all the time," she says. "If I were to rely on what I knew before this class, it was basically gut reaction and instinct. I was not really looking at the problem in a systematic way, which is what this class teaches."—P.P.P.