What Makes Us Emory

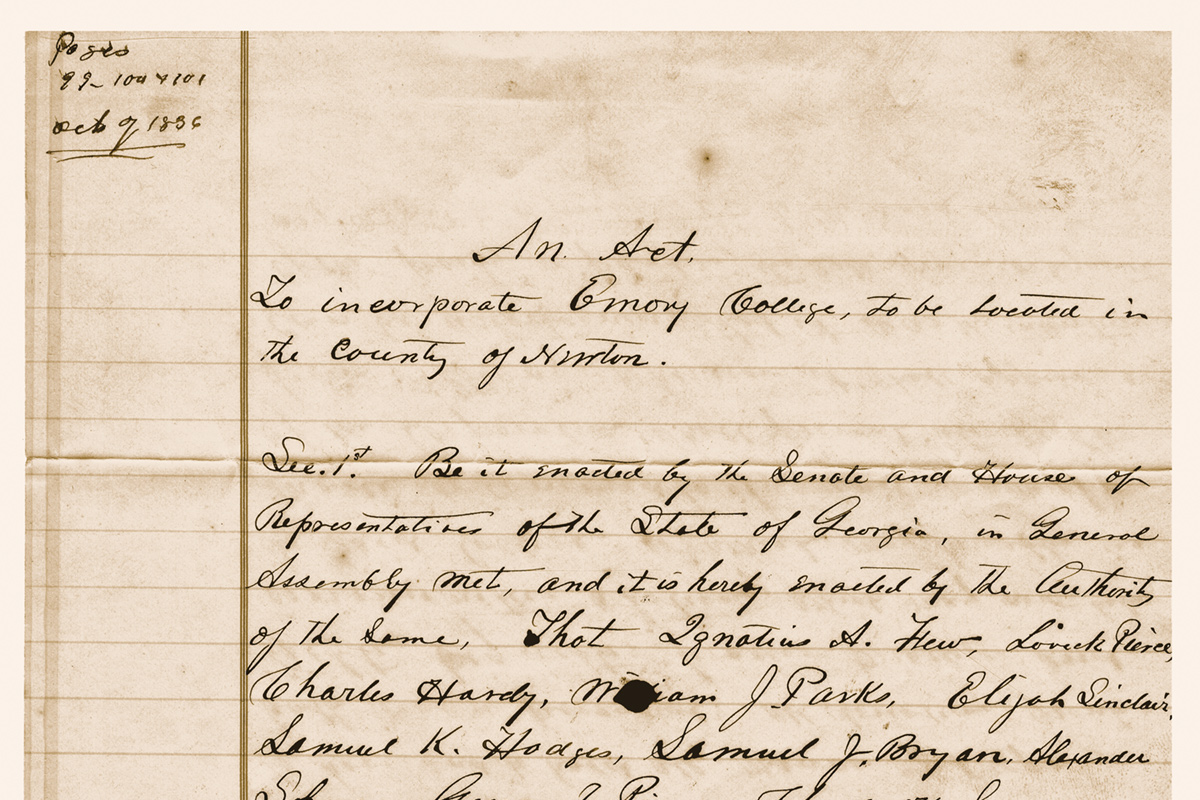

135–136. First Date

So what are we celebrating, exactly? On December 10, 1836, the Georgia legislature granted a handful of Methodist leaders a charter to start a college. Emory has its earlier roots in a school for manual labor started in 1834 by the well-intentioned Georgia Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Although that experiment failed, one of its leaders, Ignatius Alphonso Few, was determined to see it evolve. He rallied the Methodists to petition the legislature for the charter, and was subsequently elected president; the college was named for the influential Methodist bishop John Emory; and the trustees bought 1,400 acres and founded a town they named Oxford, in keeping with their grand ambitions for the school. The university marks the first meeting of the Emory College Board of Trustees on February 6, 1837, with its Founders Week celebration each year.

134. Seal of Approval

Adopted by the Board of Trustees in 1950, the Emory seal was adapted from a version developed in 1915 that marked the chartering of the university and the school’s move from Oxford to Atlanta. The current seal, designed by the late professor Thomas H. English, includes a crossed torch and trumpet representing the light and the dissemination of knowledge. They are encircled by the university’s motto, “Cor prudentis possidebit scientiam” (“The prudent heart will possess knowledge”).

137. Ultimate Icebreaker

Songfest, the spirited annual competition among first-year residence halls for best original song and performance, is new-student bonding on warp speed. Freshman orientation also features Best in Show, a provocative talent showcase sponsored by the Office of Multicultural Programs and Services that highlights cultural diversity.

138. Bare Bones

As mascots go, ours is on the eccentric side. Dooley made his first appearance in 1899 in the Phoenix, Emory’s literary journal at the time, with an essay titled “Reflections of the Skeleton.” Writing as a specimen from the Science Room, Dooley was a mournful character, complaining about the high spirits of the “college boys” who disturbed his rest. He showed up again a decade later and remained a kind of campus commentator, but his physical presence was not observed until 1941, when the Board of Trustees first allowed dancing on campus. That seems to have cheered him up. Dooley became known as a Lord of Misrule, the instigator of the festive Dooley’s Frolics, which continue today as Dooley’s Week—traditionally ushered in by the skeleton himself, who has arrived by helicopter, motorcycle, and vintage car, accompanied by his entourage of student bodyguards.

154. Who Says Print Is Dead?

The Emory Wheel (a play on “emery wheel,” a sharpening device) is the university’s undergraduate student newspaper and has been continually published since 1919; the Wheel now prints more than 5,500 copies of the paper and is available online.

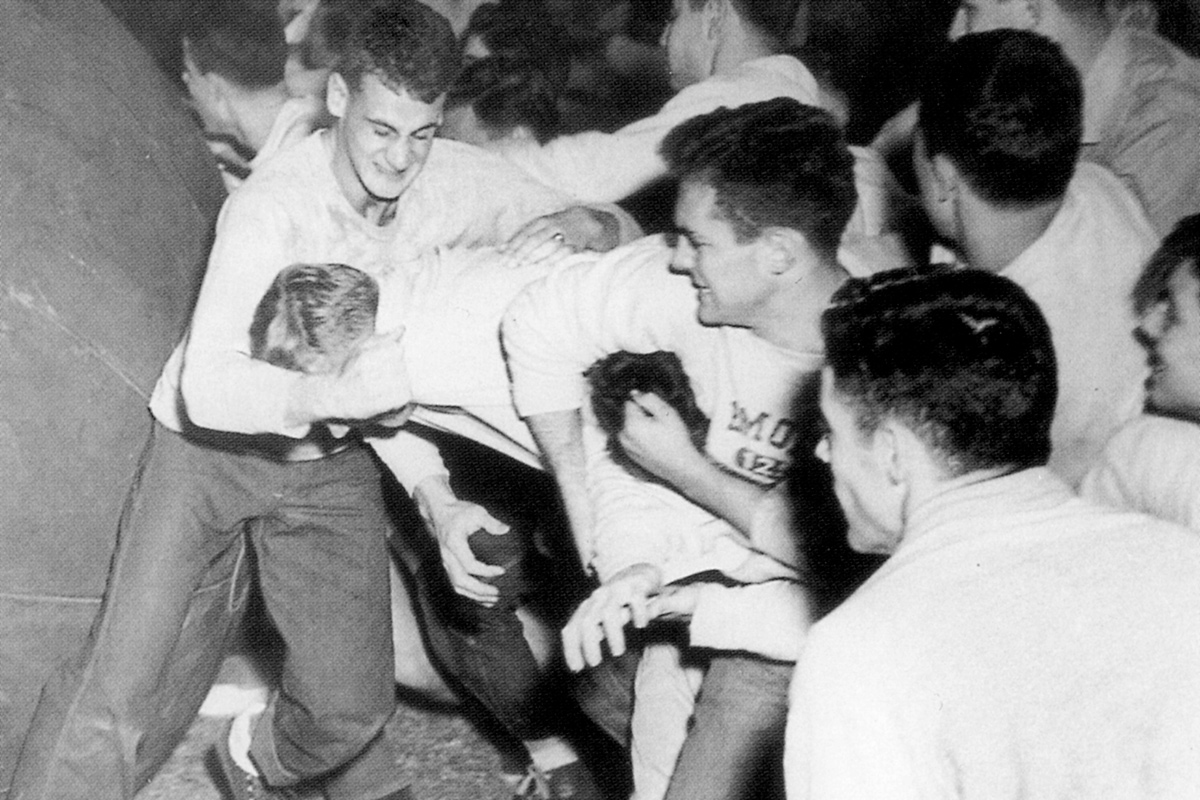

157. Pushed Too Far

The object of pushball was simple—to move the massive, 180-pound ball across the goal line of the other team—and as for the rules, there weren’t many. That may be why the annual contest between freshmen and sophomores was called off forever in 1955 after what one university official described as “mob violence.” Started in 1923, the game grew rougher with every year, and concern mounted along with concussions, broken bones, cuts, and bruises. Administrators pressed into service as referees were stripped of their pants; student refs got thrown into the cold creek nearby. And in almost three decades, the freshmen claimed only one victory. Maybe it’s just as well that the whereabouts of the giant ball has been a mystery ever since.

158. Athletics for All

It might have been President Warren Candler’s contention in 1919 that intercollegiate sports are “evil, only evil, and that continually” that gave Emory its slow start in the athletics arena. For a time in the 1920s and 1930s, the Emory Wheel carried the catchphrase, “For a greater Emory—and intercollegiate sports.” Competition with other schools was forbidden until 1945, but that didn’t stop students from playing. Emory’s intramural program, summed up by the motto “Athletics for All,” flourished from its beginnings at the turn of the century and remains lively today. Jeff D. McCord 1916C served as the first full-time athletics director and organized club teams in nearly every major (and many fringe) sports, growing student participation to 70 percent. Today it’s about 50 percent, thriving alongside the 18 varsity sports programs.

159. A League of Our Own

The University Athletic Association, which Emory helped to form in the mid-1980s, is a conference of eight institutions with a similar academic profile and a like-minded approach to sports. Since 1987, Emory has captured a total of 143 UAA championships. Emory is also a member of NCAA Division III, which does not allow athletics scholarships.

160. Crossing Cultures

Unity Month in November is a campus-wide celebration of diversity of all kinds: religious, ethnic, racial, and international.

163. We Are the Champions

The Eagles have won twelve NCAA Division III national championships: five in women’s tennis, four in women’s swimming and diving, two in men’s tennis, and one in women’s volleyball.

164. Well Rounded

Last year, 40 Emory student-athletes earned All-American status, making the total 669 since 1984. The university has been awarded 70 NCAA postgraduate scholarships, with the 53 awarded since 2000 marking the second-highest total by any NCAA member.

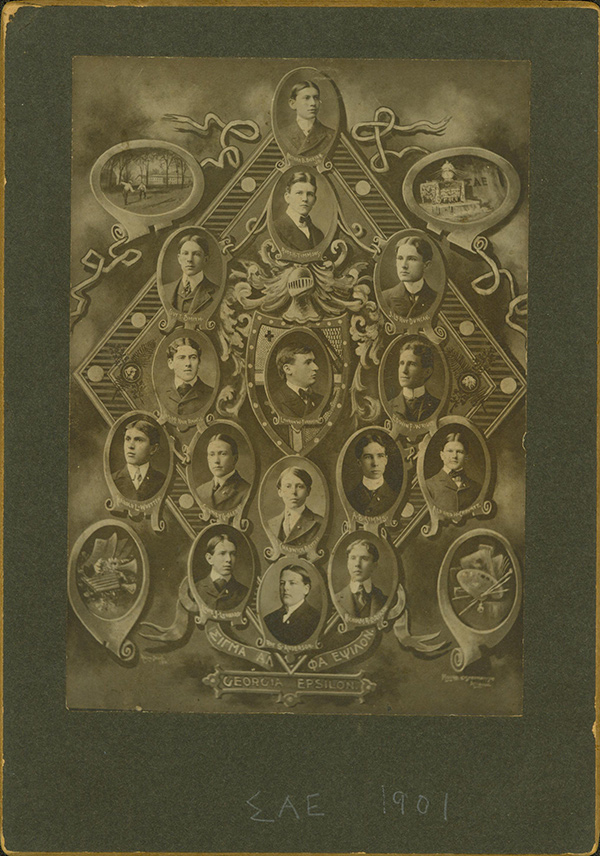

171. Great to be Greek—or Not

Nearly 40 percent of Emory students choose to join one of 12 national sororities or 14 national fraternities, but leaders say Greeks don’t dominate social life on campus. Most students belong to multiple organizations.

172. Ellmann Lectures

Seamus Heaney, Umberto Eco, Henry Louis Gates Jr., and A. S. Byatt are but a few of the fine writers and critics lured to Emory by the honor of taking the podium for the Richard Ellmann Lectures in Modern Literature. They follow the illustrious example of Emory’s first Woodruff Professor, Richard Ellmann, biographer of James Joyce and Oscar Wilde and a passionate public speaker. “Literature is really a compass that points to the true north of what it means to be a human being,” says Professor Joseph Skibell, series director. Skibell took the helm in 2008 when Ellmann founder and visionary Ron Schuchard, Goodrich C. White Professor of English, retired from the position in the lectures’ 20th year.

173. Fore!

Each year, a handful of Emory students receive the Robert T. Jones Jr. Scholarship Award for a tuition-free year of study at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, home of the legendary Old Course.

Click here to continue reading.

Our next category of note: The Circumstances of Pomp.