Celebrating Difference

110. Status Symbols

Their origins are varied, but their aims are the same: the three President’s Commissions advise the president on the needs, concerns, and progress of Emory groups. The President’s Commission on the Status of Women was created in 1976, as the number of women was growing in the ranks of both faculty and students, to guide university leadership on women’s issues. The President’s Commission on the Status of Minorities (now Race and Ethnicity) was started in 1979 after more than a decade of post-desegregation racial tensions on campus. And the President’s Commission on Sexuality, Gender Diversity, and Queer Equality (yes, that’s PCSGDQE) was officially established in 1995 as an outgrowth of an advisory committee appointed after the 1992 gay student protest. Each commission is made up of faculty, staff, and students, and plays a vital role in maintaining a diverse, safe campus community.

Visitors to the Center for Women reflect on their history at an archival exhibit.

114. Making Room for Women

In February 1990, the front page of the Emory Wheel reported two rapes on campus, both on Fraternity Row. These troubling incidents and the community’s response were the catalyst for what is now the Center for Women at Emory, which opened two years later under the leadership of its first director, Ali Crown 85C.

For 12 years, the center operated in a trailer behind the DUC, transcending its humble home to serve as a hub of activity and events for women across the university. In 2004, the center moved to new space in Cox Hall; it has been led by director Dona Yarbrough since Crown retired in 2008 and celebrates its 20th anniversary this academic year.

117. Dooley’s Rib

When Emory’s Board of Trustees voted to officially admit women in 1953, they were an uncertain 13 to 6 split, but not everyone was so ambivalent about the decision. Certainly not the jubilant male freshman who told the Emory Alumnus, “I think it’s absolutely wonderful. I’ll go hog wild. It’s the greatest thing in the world—WOMEN!” By that time, some 1,500 degrees had been awarded to women due to various special circumstances—although not to Emory’s first coed, “Mamie” Haygood Ardis (the daughter of former University president Atticus Haygood), who had to transfer to the all-women Wesleyan in 1887 to receive her diploma. The first class of women received a handbook, cleverly titled “Dooley’s Rib,” which concluded, “The Rib has a last word . . . Emory’s ideals and standards will not change. But you who are among the very first women on Emory’s campus will have the exciting chance to help set the pattern for the Emory of the future. Dooley and his Rib expect you to change things for the better—to add the feminine touch—to help us achieve more rapidly the ideals we have cherished so long.”

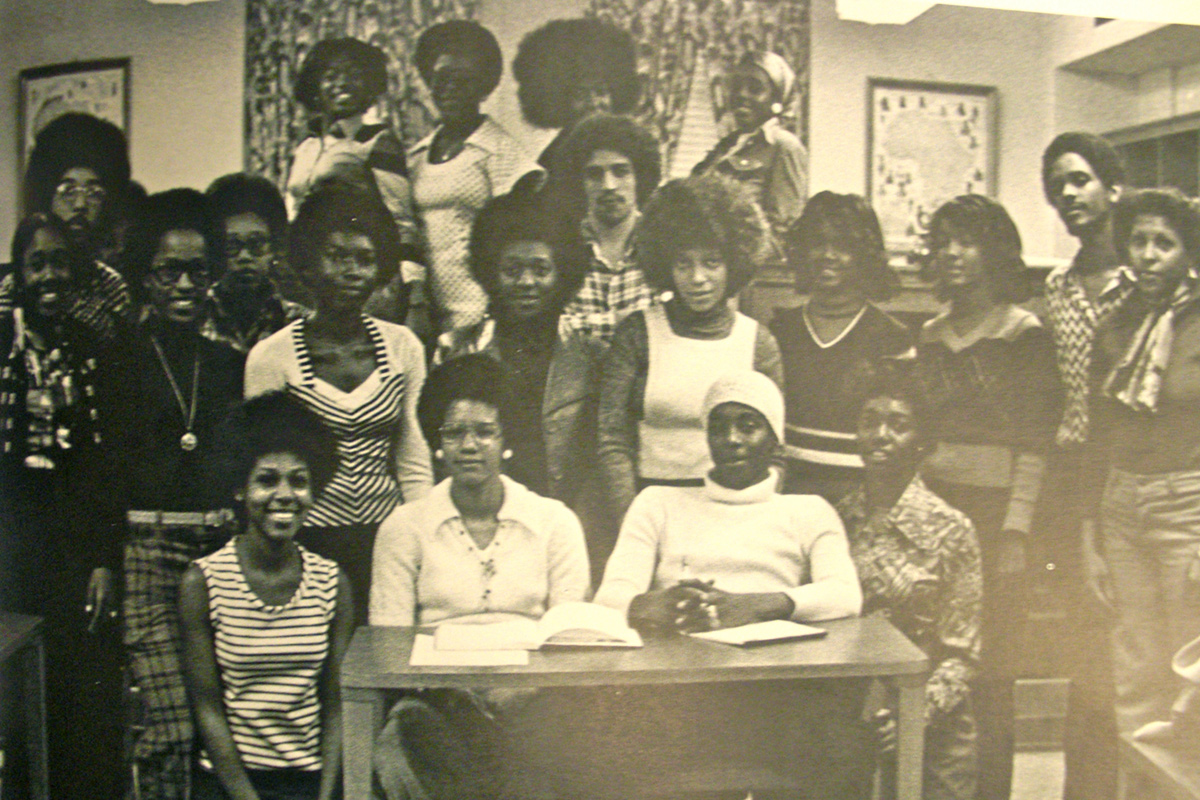

The Black Student Alliance in 1972, a decade after Emory's landmark legal challenge.

118. Critical Case

When the Georgia legislature reluctantly voted to desegregate public schools in January 1961, Emory had a problem: private schools must remain segregated or suffer a significant tax penalty. The following spring, an African American student applied to the School of Dentistry, and university leaders saw their chance. Henry L. Bowden 32C 34L 59H, the general counsel at the time, and Ben F. Johnson Jr. 36C 40L 2005H, dean of the School of Law, took the case to the Georgia Supreme Court and won—allowing Emory to admit all qualified students without penalty. Nursing students Verdelle Bellamy 62N and Allie Saxon 62N became Emory’s first black graduates in 1962.

119. Facing Differences

In 2003, an Emory professor spoke a word rarely uttered in academic circles—a racial epithet starting with “N”—when she used an outdated colloquial phrase during a panel discussion about the history of the Department of Anthropology. The outcry that echoed across campus evolved into the Transforming Community Project (TCP), a five-year, wide-ranging exploration of race and other forms of human diversity at Emory from its founding to the present. More than 1,500 students, faculty, and staff have participated in the series of candid TCP Community Dialogues (above) that were a mainstay of the project and are continuing as part of Emory’s Equal Opportunity Programs.

121. Regret and Responsibility

During Emory’s 2011 Founders Week in February, the Board of Trustees made a public statement of regret for the university’s ties to slavery, and the TCP sponsored a national, three-day conference on slavery and its historic relationship to higher education in the United States and beyond.

A 1992 march by gay students and supporters led to greater openness for the community.

127. Out of the Closet, Into the Quad

On the sunny afternoon of March 2, 1992, some 100 Emory students gathered on the Quad in an organized protest on behalf of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (LGBT) community members. The protest was sparked weeks earlier by a kiss between two male students in a dorm common area where they thought no one was around to see. About 40 residents surrounded and harassed them, and when the pair filed a complaint, they were not impressed with the administration’s disciplinary response. A groundswell of support culminated in the protest, which ended in a silent sit-in outside President Laney’s office, where the students were served Cokes while they waited. Laney eventually met with the student leaders and listened to their concerns, a conversation that led to several significant developments for Emory’s LGBT students and staff. The protest and its positive outcomes are commemorated at the annual Emory Pride Banquet in March.

128. No End of the Rainbow

Emory’s Office of LGBT Life marks its 20th anniversary this year. Founded by graduate students in 1991, the office really came into its own the following year when a full-time director, Saralyn Chesnut 94PhD, was hired at the recommendation of a presidential advisory committee. Chesnut rapidly led successful efforts to have sexual orientation added to the university’s Equal Opportunity Policy and to gain benefits for domestic partners, milestones that made Emory a trailblazer among Southern universities. Chesnut retired in 2008, when Michael Shutt took the helm as director; the President’s Commission now gives the annual Chesnut Award to a community activist in her honor.

Click here to continue reading.

Our next category of note: What Makes Us Emory.