The Unlikely Power of Pens

Illustration by Jason Raish

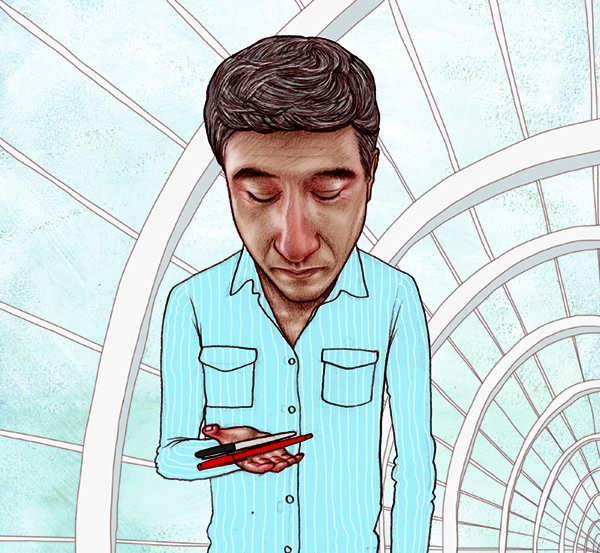

On a small plane over Southern Kenya, I reached into my bag and felt two pens, one blue and one black. They are a type of pen that I carry with me nearly every time I go into the field. I also carry a small spiral notebook, where I record all the things I see and jot down notes for my journal at night. I have a small digital camera that has been with me for the past several years; its lens has seen some of the world’s most historic moments. All of these things are part of me now, as an international health reporter for CNN. For some reason, however, feeling these pens now made my heart race and my face flush, and gave me a sudden feeling of nausea.

As a neurosurgeon at Atlanta’s Grady Memorial Hospital, where eight out of ten patients are uninsured, I have seen the face of misfortune many times. Illness and pain—and the heightened fear that accompanies disorders of the brain—are devastating for anyone, and compounded by the stress of inadequate insurance and limited access to the best care. And yet, because of our resources and infrastructure, the conditions surrounding the tragedies that affect most Americans can hardly be compared to those I have witnessed in other parts of the world.

I had been in the Dabaab refugee camp, covering the awful famine in Somalia. The stories there were among the worst I have ever seen. For the past decade, I have covered wars, natural disasters, and other calamities. I remember a child who lost both of her legs after stepping on a land mine in Iraq. There was a family standing in a decimated home in Sri Lanka, having lost all they owned. In Port Au Prince, I saw young children searching for their parents in garbage dumpsters, hoping to catch one final glimpse of them. Pakistan was full of stories of families swept away by the floods that soaked one-fifth of the nation. I have stood with a young mother at the hastily created burial site of her one-month-old baby. Her daughter had starved to death, and this poor woman had dug the grave all by herself.

When I had children of my own, I knew things were going to get especially tough. My emotions had become raw nerve endings, too close to the surface and easily provoked. I remember saying proudly to my wife on the day we were married that I hadn’t cried since I was six years old. Now, I get teary-eyed every time I think about these children, and many nights I wake up in a cold sweat. I am consumed by the fact that no matter what I do, it will likely not be enough, and that tonight kids’ bodies will shut down—for good—having been robbed of basic, basic nutrients for too long. Their hollow eyes are staring at me, and my own children are watching the whole thing unfold, so disappointed that their daddy couldn’t do more to help kids like them.

There is no dignified way to describe death by starvation. But I somehow want to pay these children homage and respect them in a world where they have been abandoned and their dignity has been lost. They are on my mind all of my waking hours and in my dreams at night. Truth is, I am not sure I want them to ever leave.

Last night, I dreamt about pens. Hundreds and hundreds of pens. I had bags and bags of them, and I was handing them out to every kid I could find, their big smiles filling a deep, gaping hole that I didn’t even realize I had. Blue pens, black ones, red, green—even purple. The children would take the pens and immediately start writing. Sometimes with remarkably good penmanship, sometimes amazing drawings, sometimes just lines and shapes with personal meaning. They would show me their work, happy to have some sense of permanence for the first time in their lives, even in the form of an ink stain on their small, dirt-covered hands.

Helplessness for me means the sudden realization that senseless, stupid deaths will occur in a world that can at times be so beautiful. Helplessness for me means not being entirely sure how we can continue living in a world that would allow hundreds of thousands of kids to starve to death. Helplessness for me means watching a young child beg for a pen, so they can make a mark somehow, as if screaming: I am here, but I will soon be gone. Please, don’t forget me.

Helplessness for me means reaching into my bag and feeling two pens. I wish I had given them away, to offer just a little ray of happiness in a harsh world. I wish I could have done more for all of our children.

What I can do instead is use those pens—and my notebook, and camera, and microphones and videos and live satellite feeds and all the considerable tools in my power—to tell their stories. To let the world know that those children were here, that they spoke and laughed and breathed. And that many of them still have a chance.

Sanjay Gupta is chief medical correspondent for CNN, assistant professor of neurosurgery at Emory's School of Medicine, and associate chief of neurosurgery service at Grady Memorial Hospital.

Email the Editor