Patterns in Black and White

Emory is serious about facing its Southern past—and having a voice in the national conversation on race

Emory acknowledges its entwinement with the institution of slavery throughout the College's early history. Emory regrets both this undeniable wrong and the University's decades of delay in acknowledging slavery's harmful legacy. As Emory University looks forward, it seeks the wisdom always to discern what is right and the courage to abide by its mission of using knowledge to serve humanity.

On February 6, Emory's Oxford College hosted a family reunion—of sorts.

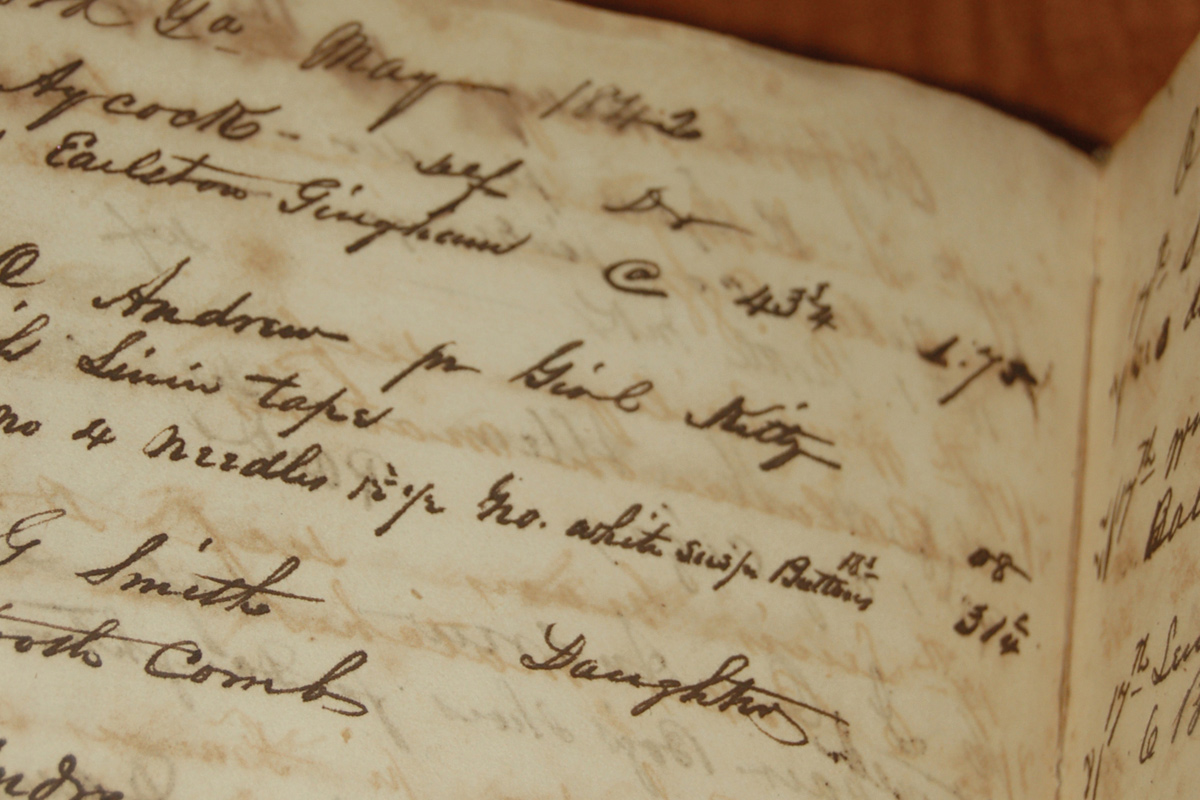

In attendance were siblings Darcel and Cynthia Caldwell, who had traveled from Pennsylvania to pay homage to their great-great-great-grandmother, Catherine "Miss Kitty" Andrew Boyd.

Also present was Virgil Eady, a direct descendant of Emory professor and slave owner George Stone; and Callie "Pat" Smith, one of the first students of color at Oxford, whose ancestors laundered the clothes of white Emory students in the institution's early days.

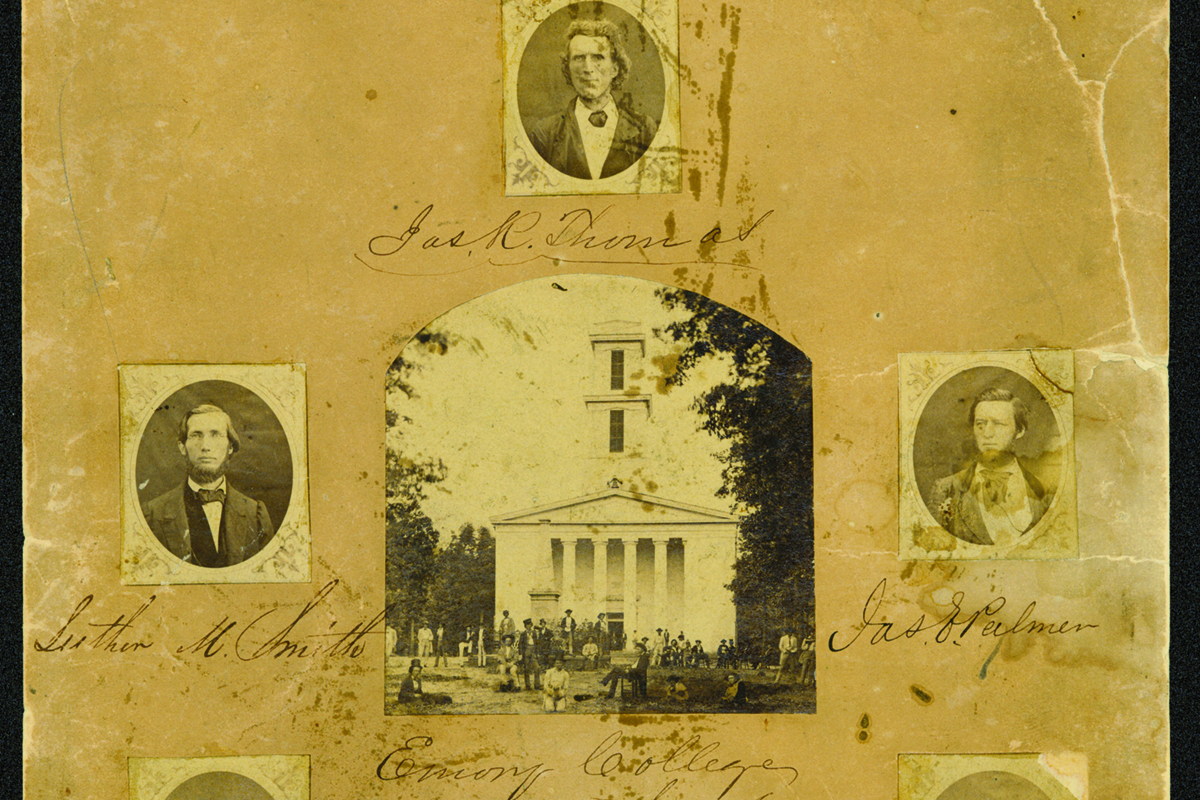

Miss Kitty was the memory who brought them together for what historian Hank Klibanoff, James M. Cox Jr. Professor of Journalism, called "an expression of institutional genealogy." Though their DNA is not shared, they are all connected by Emory's past as a university that used slave labor to build its campus. This gathering in Oxford had its origins in what is arguably the ugliest reality in history; the hands that built the Oxford campus in 1836 implicated many of Emory's founders, who not only kept slaves but vociferously defended the practice.

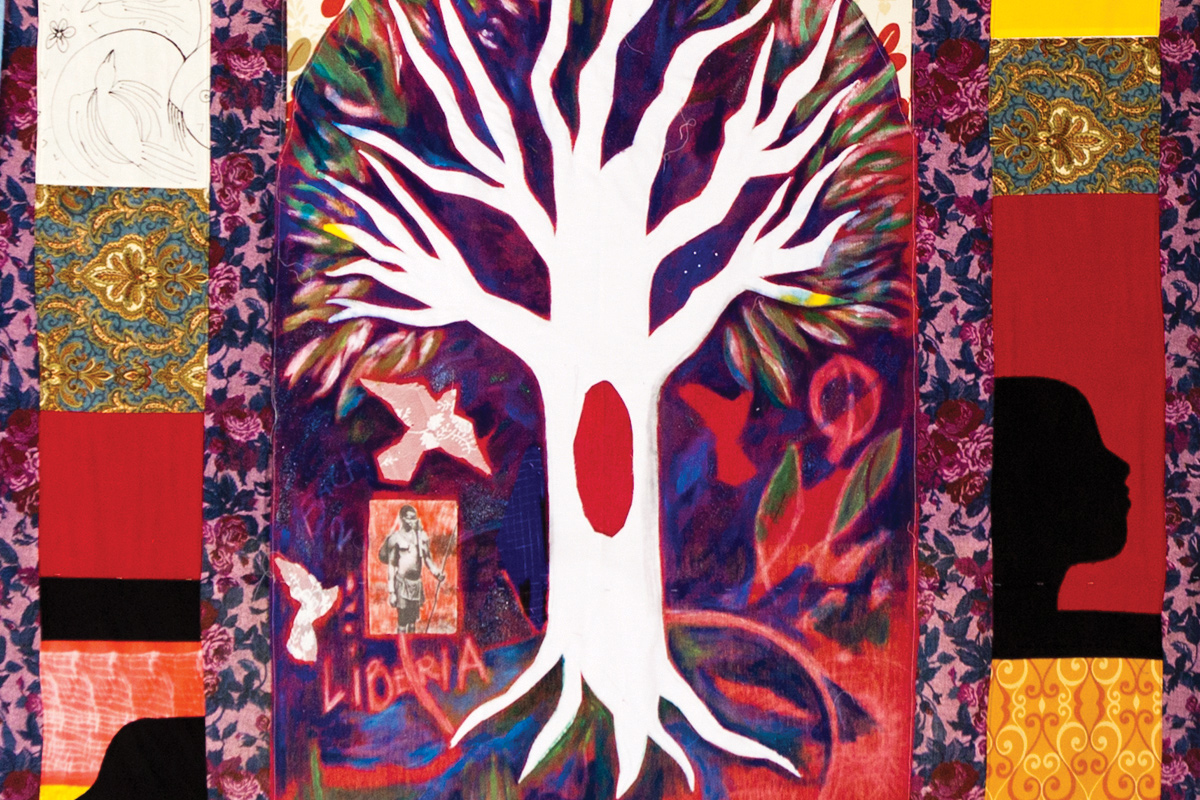

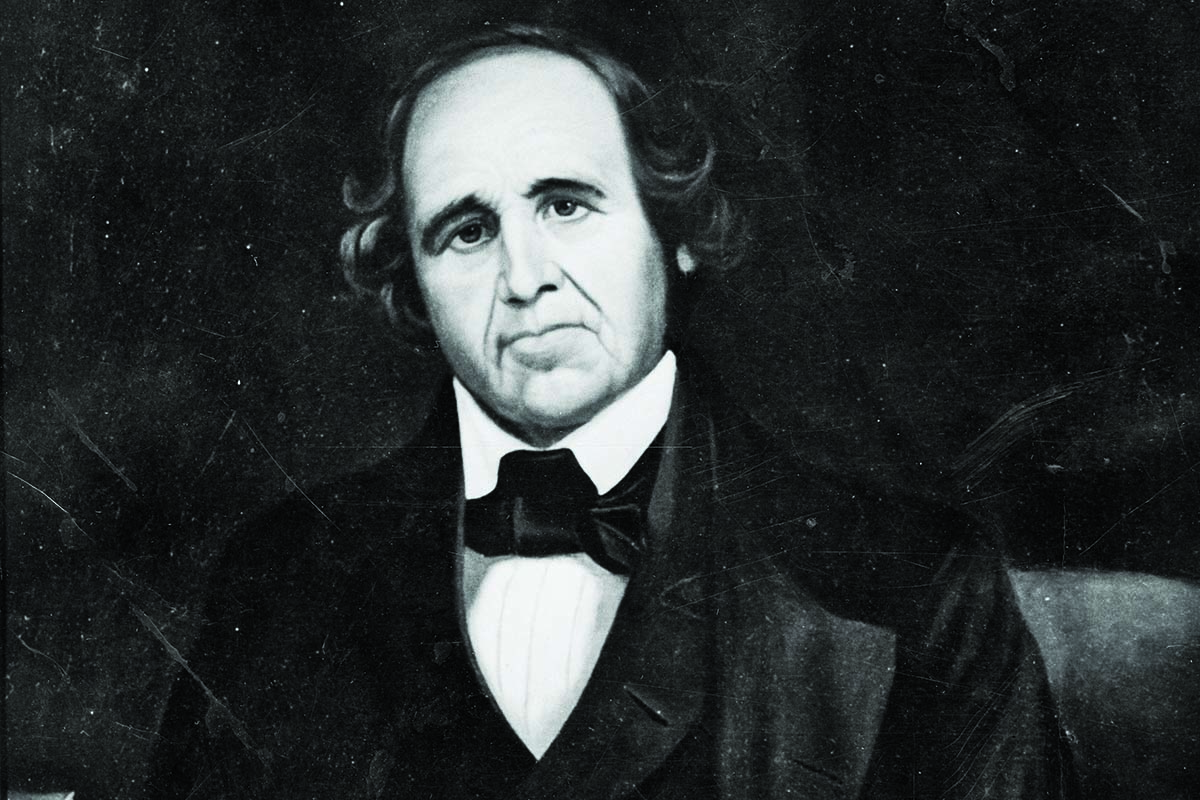

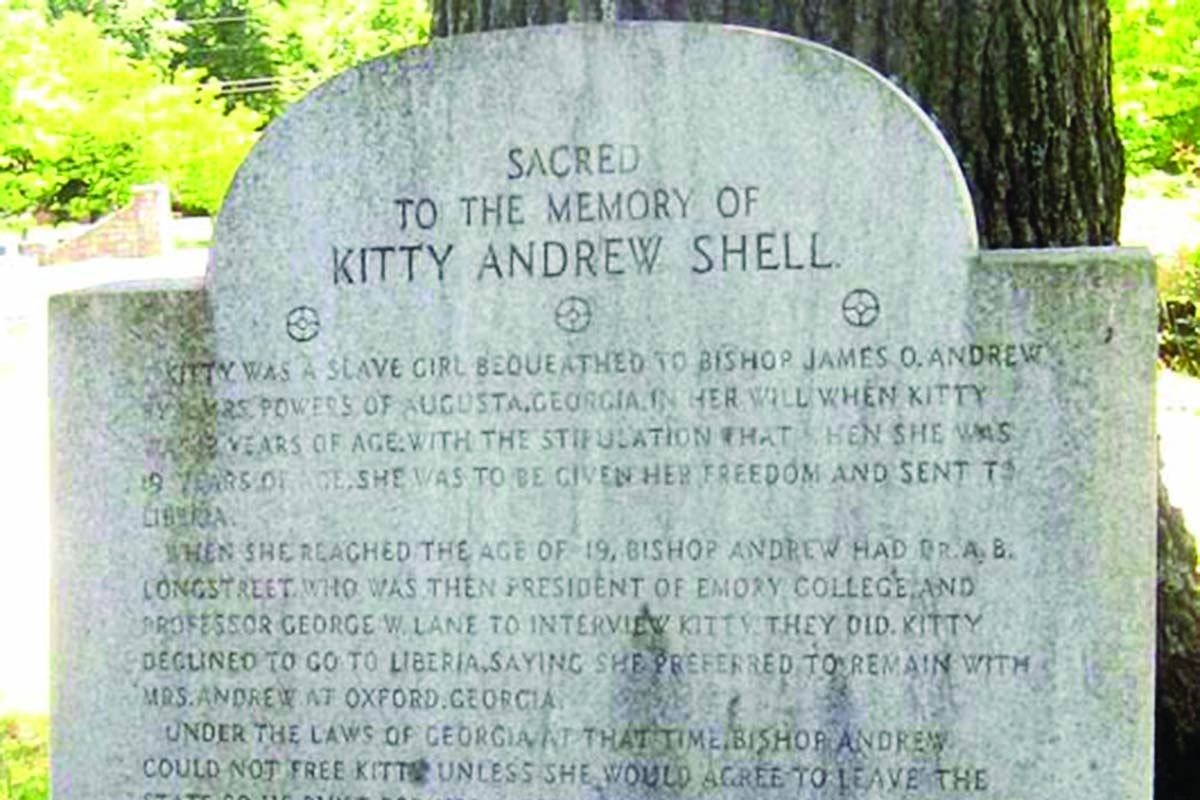

Kitty was one of twenty slaves owned by the first president of Emory's Board of Trustees, Bishop James Osgood Andrew. And she has become a potent symbol for the Southern schisms that still linger. Her symbolic value is examined in former Oxford anthropology professor Mark Auslander's forthcoming book, The Accidental Slaveowner: Revisiting a Myth of Race and Finding an American Family. It was Auslander's pioneering research into Kitty's past that set the stage for the revelations that day at Oxford.

To whites, Auslander observes, Kitty once seemed to illustrate the myth of the devoted and loyal servant and the implication that slavery was, somehow, a benevolent—or at least benign—way of life.

To blacks, she symbolized the ravages of slavery, the denial of freedom, and speculation that she was forced into a sexual relationship with Andrew. Kitty had national significance, too: slave owning among Southern Methodists like Andrew triggered the split in the Methodist Episcopal Church that presaged the American Civil War.

As so often happens in families, Miss Kitty is evidence of how wildly versions of the past can diverge according to one's perspective.

The gathering in Oxford was the culmination of a landmark four-day conference hosted by Emory, "Slavery and the University: Histories and Legacies." During the course of the summit, 250 participants, including faculty from Harvard, Brown, and Spelman, gathered for an open discussion of American public and private universities' ties to slavery.

"The importance of enslaved labor to all kinds of institutions is America's, and indeed the world's, biggest open secret," said Leslie Harris, associate professor of history and an organizer of the conference, at the opening event.

Brown University President Ruth Simmons delivered the keynote address, outlining Brown's three-year effort to document its eighteenth-century links to slavery. A committee convened in 2003 to unearth the complex relationship between the New England slave trade and the founding of the university. Its work culminated in a 2006 report recommending that Brown create a center devoted to the study of slavery and injustice, raise a $10 million endowment to help educate children in Providence public schools, and rewrite its history in time for Brown's 250th anniversary in 2014.

"I think of this as a persistent effort to understand why we are who we are," Simmons said. "This rigorous review is absolutely essential."

"Slavery and the University" came on the heels of the January statement of regret from Emory's Board of Trustees for the school's connections to slavery. "Emory bears an inescapable legacy involved in the institution of slavery and its long and painful aftermath," President James Wagner said in his opening remarks. "These are facts of history. They should not be disputed or avoided."

What the conference represented, Harris says, was the intention of Emory scholars to engage with historical projects that illuminate slavery's history for the good of the present.

"You can't really make sense of race in America without slavery," says Auslander, who also helped organize the conference. "And for a long time there's been a great unwillingness to face up to the complexities of the stories of slavery in American life. And that's where I think Emory is pushing the envelope in a lot of exciting ways."

"It made me realize," Klibanoff adds, "how closely connected we are in time and space to the past. Going to the gravesite of Miss Kitty and seeing her relatives, that was very powerful. I was just in awe of the process of discovery."

Hard Questions

That process of discovery—whether through historical research, or as it played out in the conversational circle on that day in Oxford, Georgia—is central to Emory's effort to distinguish itself in the field of African American studies by engaging with stories that are admittedly hard to tell.

African American studies chair Mark Sanders acknowledges that there is a great deal of fear and guilt involved, resulting in "the issue of Southern whites perhaps feeling indicted or put on the spot." But, he cautions, "even with the reality of that existence in some quarters, we should recognize that there continue to be lots of people really hungry and yearning for open interracial discussions about race."

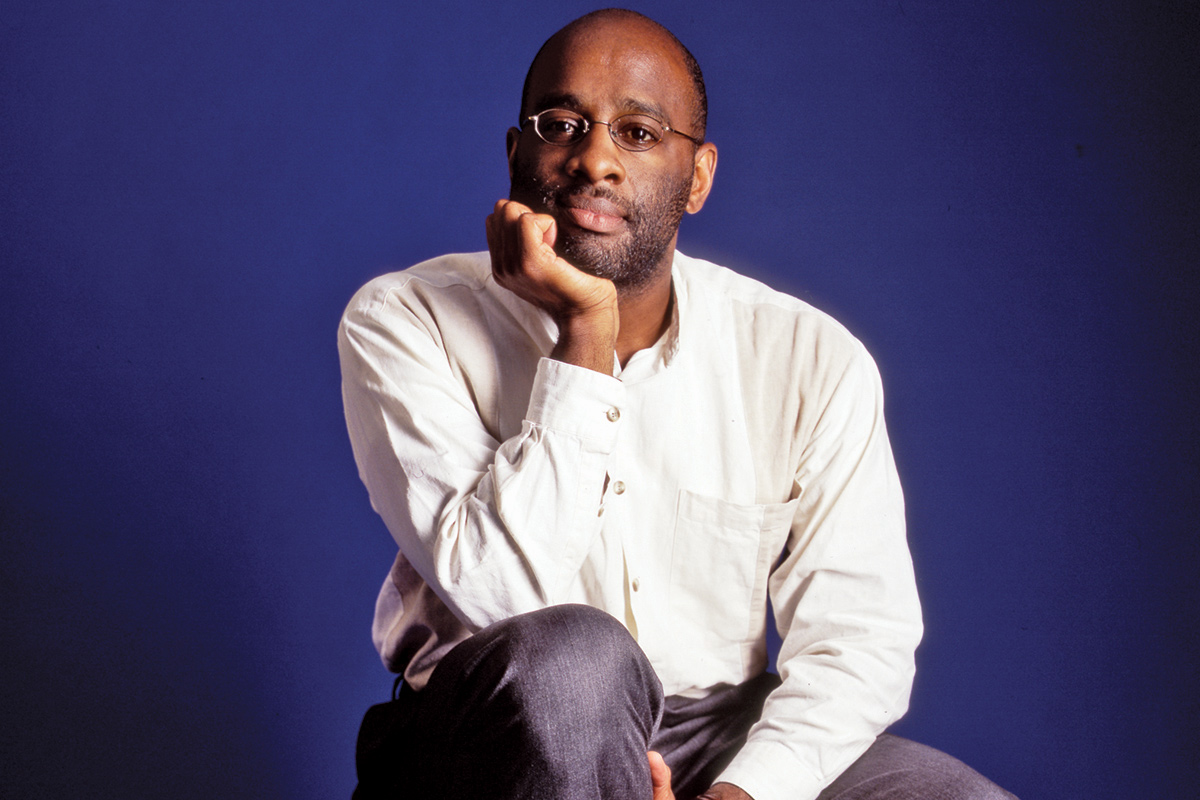

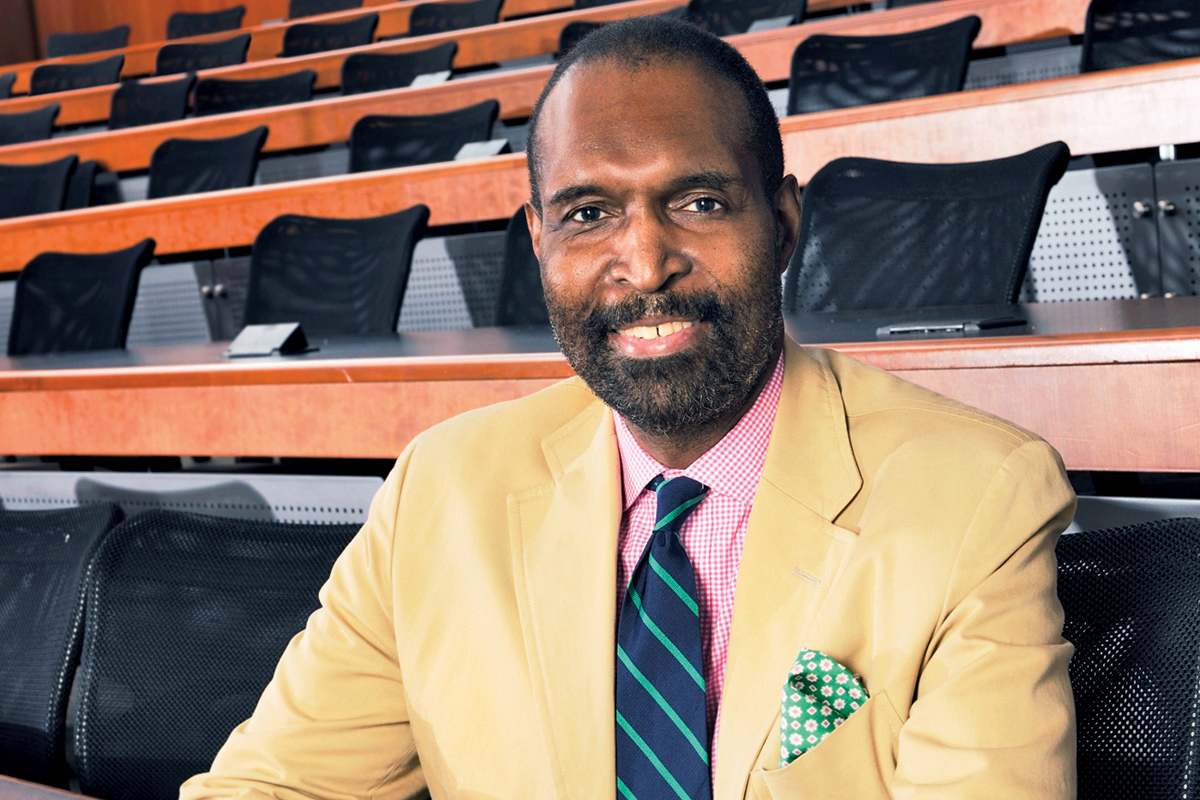

One of those discussions is taking place around the recent and widely noted collaboration of Goodrich C. White Professor of American Studies professor and director of the James Weldon Johnson Institute, Rudolph P. Byrd, and Director of Harvard's W.E.B. Du Bois Institute Henry Louis Gates Jr., who cowrote a controversial analysis of the Harlem Renaissance figure Jean Toomer. Author of the revered African American book Cane, considered a pivotal work of literary modernism when it was published in 1923, Toomer strove to shed new light on the black experience—and, according to Byrd, he still does today.

"His life and positions around race reflect some of the conversations that we are now having about race as a social construction," says Byrd. "Toomer as a pioneering thinker and writer on race was one of the first to contest the so-called one-drop rule and argue for more expansive definitions of race. But unfortunately Toomer didn't stop there. He also sought to deny his own racial background."

Born to a former Georgia slave and educated at African American schools, Toomer argued against essentialist definitions of race. But Gates's and Byrd's research—presented in their extensive introduction to the 2011 Norton edition of Cane—led them to conclude that in later years, Toomer took his own notions of race as self-defined to an extreme in his decision to pass for white. That choice of a half-century ago taps into current tensions surrounding whether race is increasingly malleable; is it the sum total of experience, a component of that experience, or of so little consequence that we now live in what some have termed a "post-black" age?

Toomer, the authors write, was "a pioneering theorist of hybridity, perhaps the first in the African American tradition. Nevertheless, he remained indifferent to the consequences of this position, and quite determined to maintain and justify it, returning to the subject seemingly endlessly in his autobiographical writings."

"I think that his life and example raise very interesting questions for us at a time when we are still struggling with race," says Byrd. "On the new census there are more than fourteen different categories for self-identifying. This is completely new. Americans are exercising the right to identify themselves in very specific ways. I do hope Americans don't fall into Toomer's pattern of denial, but that they engage in an honest way with questions related to race. And that they understand that race tells us something, and then nothing at all about an individual."

For Gates, the study of Toomer's conflicted racial identity remains highly relevant. "It's timely that our edition of Cane was published when there is the first black president in an era of so-called 'post-blackness,' " Gates says. "In my opinion, an era of post-blackness will only exist when we are post-racism. And I don't know about down in Atlanta, but up here such an era is nowhere in sight."

Past Made Present

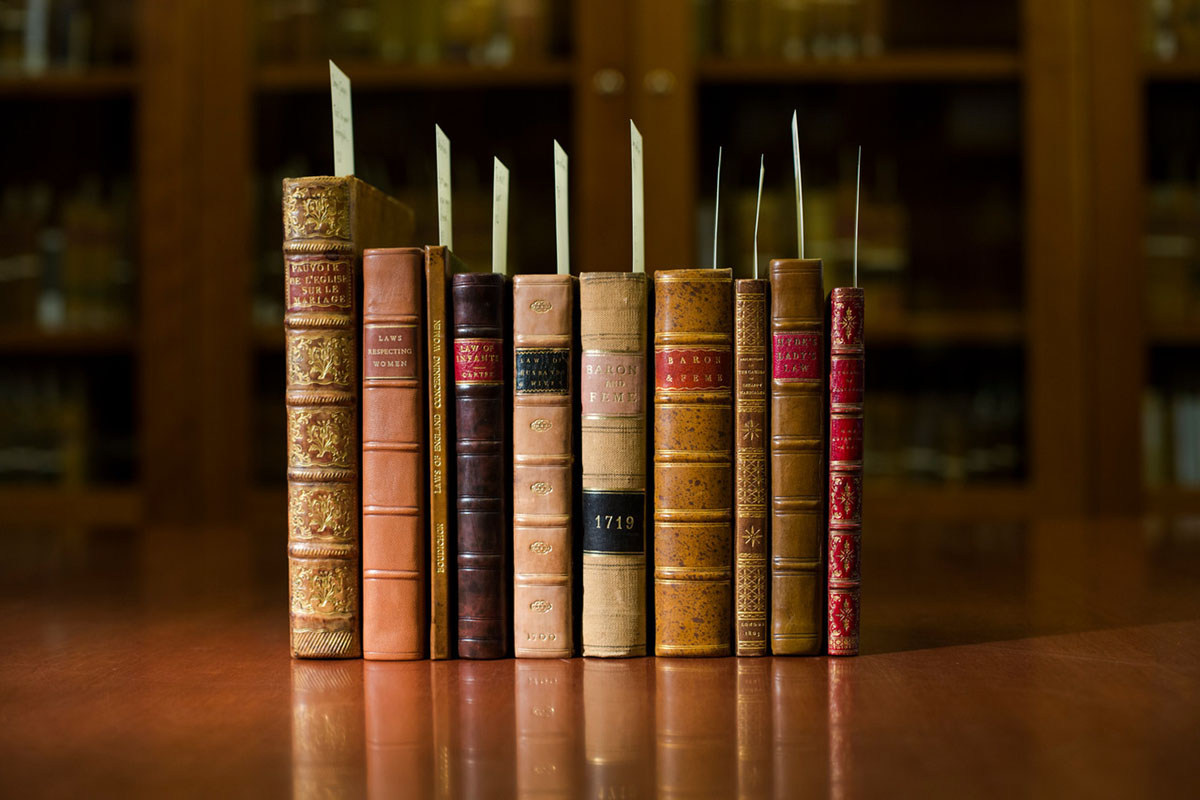

In addition to those who work and teach here, scholars from around the country are drawn to the African American Collections of Emory's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library. Researchers can grasp history in African American church fans and political pamphlets, in the documents of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, in the Alice Walker papers, in a book of poetry signed by ex-slave writer Phillis Wheatley.

The collection of documents, culled by curator Randall Burkett since 1997, is available not just to scholars, but to anyone in the community interested in furthering their understanding of African American history. "It's not just locked up in its traditional ivory tower," says Ginger Cain, director of public programs for the Emory Libraries. And its caretakers are not, cautions Cain, "the don't-touch-my-stuff archivists."

"Emory's commitment to the field of African American studies is indicated in the most subtle and important way by the hiring of Randall Burkett," says Gates. "That is how Yale became dominant in African American studies in the seventies, because it had the best archival collection."

Historical excavation in service of the present is also central to the work of David Eltis, Robert W. Woodruff Professor of History. Working alongside scholars and information architects both at Emory and outside the South, Eltis led the research project and exhibition "Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database," which highlights the economic and social impact of more than 35,000 slave voyages from Africa to the Americas from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, all documented in the database.

"All these initiatives draw attention to the extreme, centuries-long exploitation of peoples of African descent," Eltis says. "But for me, they also underscore the huge shift in social norms or values that can occur in a relatively short time, and how poorly we understand why this happens. A little over two centuries ago, slavery was an accepted institution in almost every society in the world and had been for millennia. Today, it is so widely regarded as the apotheosis of evil, nowhere supported by the law, that it is almost impossible to comprehend premodern history."

Southern Cross

The University's ties to the history of the South still cast a shadow, but they also serve as inspiration for current research, creative writing, and cultural dialogue and trends.

Natasha Trethewey, Phillis Wheatley Distinguished Chair in Poetry and a Pulitzer Prize–winning poet, highlights the lingering barriers of skin color and class in her most recent book, Beyond Katrina: A Meditation on the Mississippi Gulf Coast; and Kevin Young, Atticus Haygood Professor of English, reenvisions history in another way in his epic poem on one of slavery's most famous rebellions, Ardency: A Chronicle of the Amistad Rebels.

Auslander points to the Emory Libraries' online journal Southern Spaces, edited by Associate Professor of American Studies Allen Tullos, as a site where the ethos of the South is continually reimagined. "A lot of the most important writing about race and place and power is coming out of that journal," he says. "All institutions should be doing this kind of work, but it's very important for Southern institutions to be taking the lead."

Atlanta set the stage for the University's involvement with the "Without Sanctuary" exhibition of lynching photographs at the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site in 2002, and the establishment, led by Byrd, of the Johnson Institute in 2007—tasked with studying the origins and legacy of the civil rights movement.

"Being in Atlanta is enormously important in my opinion," says Sanders. "The major twentieth century response to slavery and its residual effects is the civil rights movement, and Atlanta is the cradle of the civil rights movement."

The Transforming Community Project (TCP), founded at Emory in 2005 to foster communication about race, has been an agent of storytelling too, as various members from Emory's community come together to offer their version of reality to measure others against.

"One of the things we've done is make people more comfortable with the idea of talking about race openly," says TCP's cofounder and director Harris, while "recognizing that we're not going to come to some grand agreement."

Funded in part by the Ford Foundation's Difficult Dialogues initiative, TCP's focus on "history-making" has led to disclosures about Emory's past, including its connections to slavery. And as with Brown University's self-investigation of slavery's practice in its ranks and in the North, Harris's writing has countered common wisdom about slavery's scope, particularly in the North.

Revisiting the stories of Southern history can help shape the present in a number of ways, but perhaps few are as immediate as the work being done by Klibanoff in examining past cases of racially motivated crimes. His Civil Rights Cold Case Project aims to unearth and even untangle the unsolved murders of civil rights workers, and serves as the foundation for a class Klibanoff will teach alongside assistant professor of African American studies Brett Gadsden this fall.

Klibanoff hopes their exploration of these cases nearly a half-century old will illuminate a pattern of evasion in American history that persists today—not to mention ease the hearts of descendants of the crime victims.

"I think there are large segments of the population who are in denial," says Klibanoff, who grew up in Alabama and coauthored the 2007 Pulitzer Prize–winner The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation. "There are segments that are blissfully ignorant and there are probably some who purposefully don't want to know. But I also think there is another large segment that's deeply hungry for the total story. I think that history still has huge gaps for a lot of people. . . . I grew up in the South, where history was written for white people."

Slavery may be a distant, dark memory in American life, but its scars run deep, and they don't end at the Mason-Dixon Line. Events like Hurricane Katrina, President Obama's election and the often vicious critiques of his presidency, and cities that remain effectively segregated remind us that a "post-black" world is not yet upon us.

"When we look at the length of time in which African Africans were held enslaved, to expect that five-hundred-plus years of outright oppression would then be rectified in forty to fifty years is ludicrous," Harris says.

In her book Beyond Katrina, poet Natasha Trethewey notes how some people she meets on a visit to her hometown on the Gulf Coast after the hurricane remember the storm's aftermath in a way that allows them to gloss over many of the more brutal elements.

"I know that a preferred narrative is one of the common bonds between people in a time of crisis. This is often the way collective, cultural memory works, full of omissions, partial remembering, and purposeful forgetting," she writes. "People on both sides of a story look better in a version that leaves out certain things."

But, she cautions, there is no power like the truth: "It is another way that rebuilding is also about remembering."