Carrion, and Lighter Fare

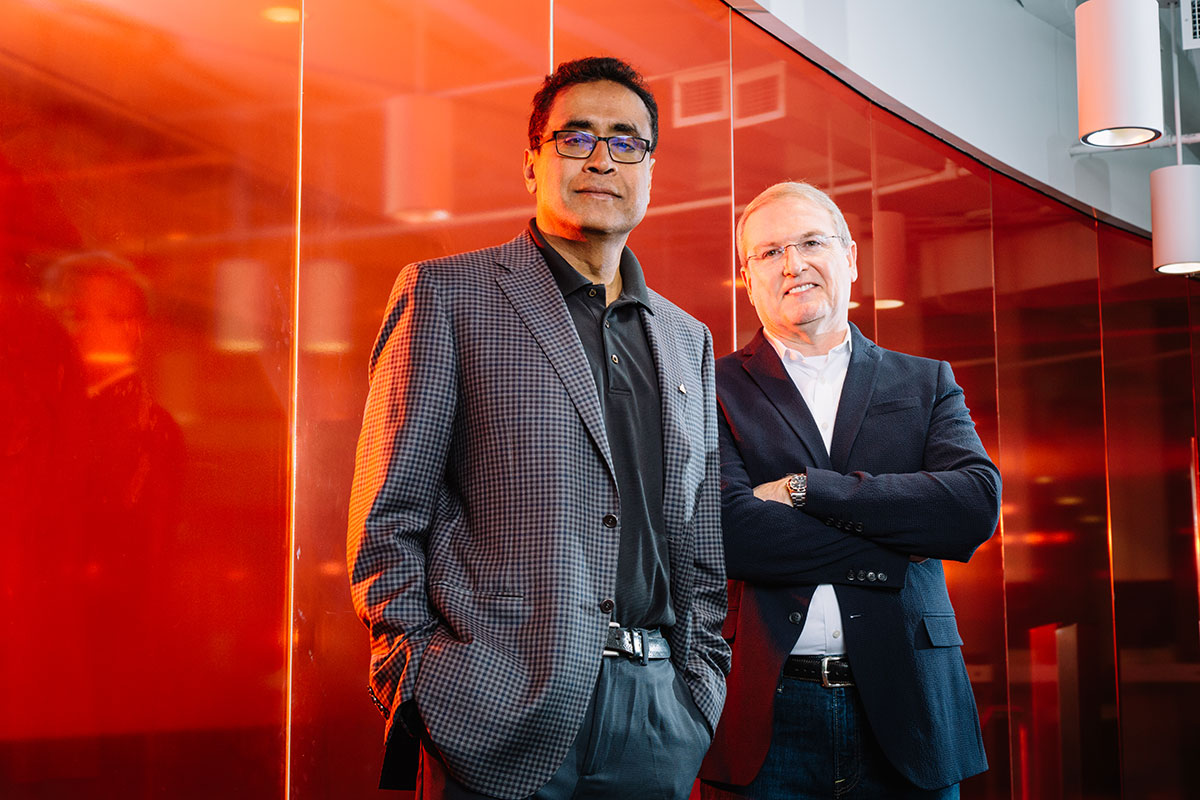

The 2018 Feast of Words celebrates 109 faculty authors with wide-ranging tastes

To salute those who triumph over the blank page or screen, Emory has an annual, and convivial, answer: the Feast of Words—a celebration of our published authors and editors. This year’s output includes 115 books authored by 109 faculty members. There were sixty-nine single-author books, twenty- two multiauthor books, and sixteen edited volumes.

“Everyone in this room who has written a book knows what an incredible endeavor it is,” said President Claire E. Sterk at the February event. She drew laughs by quoting from the British writer Somerset Maugham: “There are three rules for writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are.”

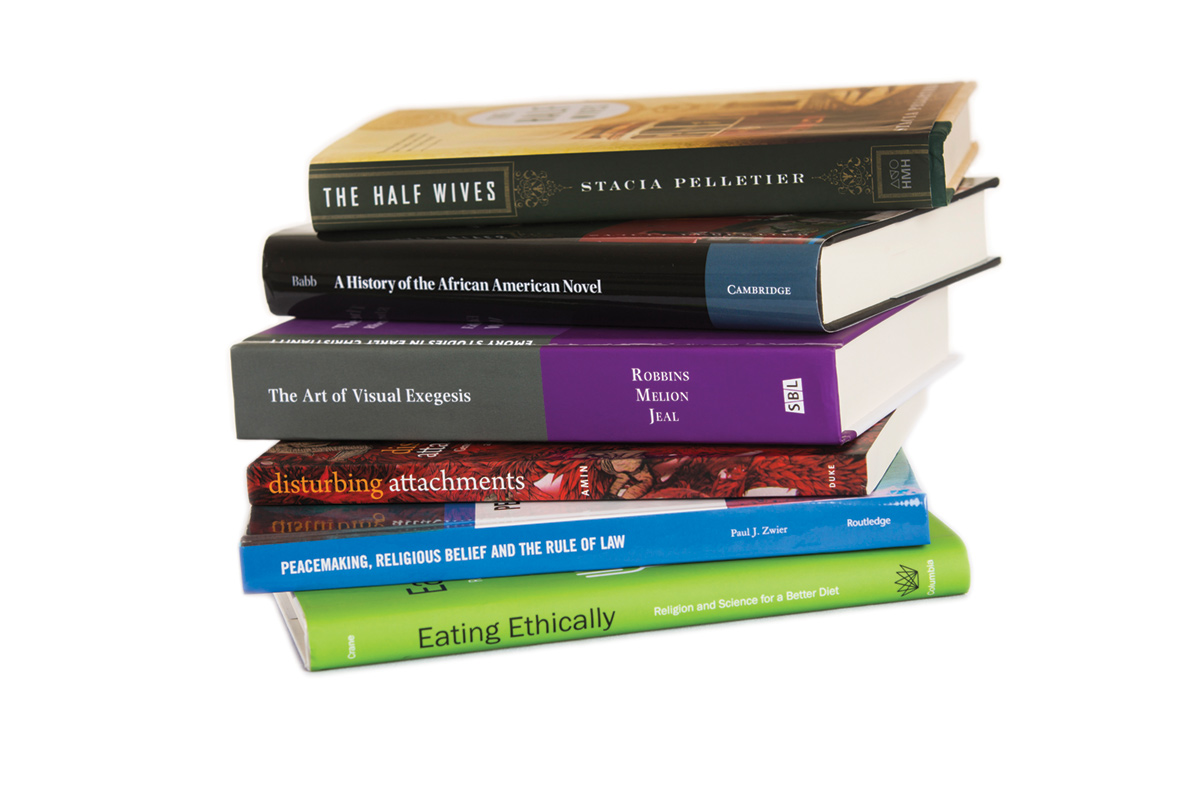

We’ve gathered a few noteworthy titles that offer a taste of the larger feast.

A History of the African American Novel

By Valerie Babb

Valerie Babb begins with refreshing directness in an introduction subtitled “The Problem with the Title of This Volume.” Revealing that the publisher chose the term African American, Babb, Andrew Mellon Professor of Humanities with a joint appointment in African American studies and English, notes that each novelist she includes had a different sense of the term. As she says, “The many events, considerations, and reconsiderations that went into creating an identity variously called black, colored, negro, Negro, African American, Afro-American,African American, and black again, over the course of the seventeenth to the twenty-first centuries, reveal much about how different nations and ethnicities were coalesced into race.”

She identifies the 1970s through 1990s as the “watershed moment when black novels received national and international accolades.” As figures such as William Bennett and Lynne Cheney protested the turn away from classic literature toward the literature of identity politics, African American scholars challenged the way literary histories were formed.

In the last of nearly five hundred pages, Babb returns to the theme of“novels of necessity”—the nineteenth- century novels “charged with proving black humanity and intellect.” “Perhaps they [African American novels] should once again become a literature of necessity because their arguments for the humanity of black Americans are needed to advocate for the respect of all human life; their arguments for equal measure under the law are needed as reminders of the social justice work that still must be done.”

Disturbing Attachments: Genet, Modern Pederasty, and Queer History

By Kadji Amin

Kadji Amin—assistant professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies—reveals that after investigating the French writer and political activist Jean Genet in his dissertation, he was ready to quit him. He credits a colleague with convincing him that, “rather than moving on in search of a better object, I might write a good book by thinking through Genet’s disappointment of my scholarly ideals.”

And so he has written a good book, using Genet to interrogate his discipline. Calling it “cogent, timely, and pathbreaking,” scholar Sharon Patricia Hollandwrites, “Queer studies desperately needs this book.”

Eating Ethically: Religion and Science for a Better Diet

By Jonathan Crane

The Vulture eats between his meals

And that’s the reason why

He very, very, rarely feels

As well as you and I.

His eye is dull, his head is bald,

His neck is growing thinner.

Oh! What a lesson for us all

To only eat at dinner.

—Hilaire Belloc, More Beasts for Worse Children (1897)

That’s how Jonathan Crane, the Raymond F. Schinazi Scholar in Bioethics and Jewish Thought at Emory’s Center for Ethics, chose to begin.

While poking around in the field of bioethics for discussions about eating-related ailments, Crane found that religious and philosophical traditions, and even contemporary physiology and the scientific study of eating, diverged significantly from contemporary eating strategies.

Crane’s advice? Focus “on what it means for each individual to be sated.” As he says, “How and why we eat are two of the most urgent and pressing ethical questions of our very existence, and their answers lie daily in our own hands and mouths.” By heeding those words, no one need suffer the fate of Belloc’s vulture.

Peacemaking, Religious Belief, and the Rule of Law: The Struggle between Dictatorship and Democracy in Syria and Beyond

By Paul Zwier

Paul Zwier’s latest book uses Syria to explore ideas of leadership and nationhood. He examines the role of religion in the actions of Bashar al-Assad, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and conservative US Christians. And the professor of law hones in on “the role of the mediator in teaching parties the interrelationship between sustainable peace, forgiveness, and international justice.”

Ultimately, he circles back to the US and hopes his book will be “a warning” that democracy is eroded not in a single election or other action but by attrition, courts, legislatures, and people looking the other way. “Democracy is fragile, as is peace,” Zwier concludes.

The Art of Visual Exegesis: Rhetoric, Text, Images

Edited by Vernon Robbins, Walter Melion, and Roy Jeal

This volume arose out of the Sawyer Seminars held at Emory during 2013–2014. Robbins is professor of New Testament and comparative sacred texts in the Department and Graduate Division of Religion at Emory; Melion is Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Art History at Emory; and Jeal is a professor of religion at Booth University College.

A critical study of the intersection of art and biblical interpretation, the book consists of twelve essays from biblical scholars and art historians that merge rhetorical interpretation and cognitive studies with art historical visual exegesis to interpret rhetography in biblical materials.

The Half Wives

By Stacia Pelletier

Stacia Pelletier 07PhD, chief writer in the Office of the President, is an accomplished fiction author: Her first novel, Accidents of Providence, was short-listed for the Townsend Prize in Fiction.

With this work, she presents Lucy and Marilyn, both of whom have a relationship with Henry, though they have never met and Marilyn doesn’t know of Lucy’s existence. Set in 1897, the characters— along with Henry and Lucy’s daughter, Blue—eventually converge at the city cemetery on the outskirts of San Francisco, where Marilyn and Henry’s son was buried sixteen years ago. Pelletier manages the novel’s events in a single twenty-four-hour period.

According to Kirkus Reviews, “Well-crafted characters struggling alone with a shared grief furnishes a coursing river on which this intriguing story effortlessly flows.”