From the Mouths of Babes

Baby teeth may reveal the impact of maternal stress on a developing fetus

Kay Hinton

Ever wonder what happens to all the teeth the tooth fairy collects? If they come from the children of participants in Professor of Psychology Patricia Brennan’s research, they may wind up in her Emory research lab.

Brennan has been awarded $100,000—one of three Emory recipients of grants from the Brain and Behavior Research Institute (see sidebar)—to pursue a study titled “Out of the Mouths of Babes.”

The idea, according to Brennan, is to determine how mothers’ depression and stress during pregnancy may influence the brain and cognitive development of their fetuses, and the likelihood of these children developing related problems themselves.

What sets her investigation apart from previous studies on the subject is that Brennan is gathering insight by examining baby teeth.

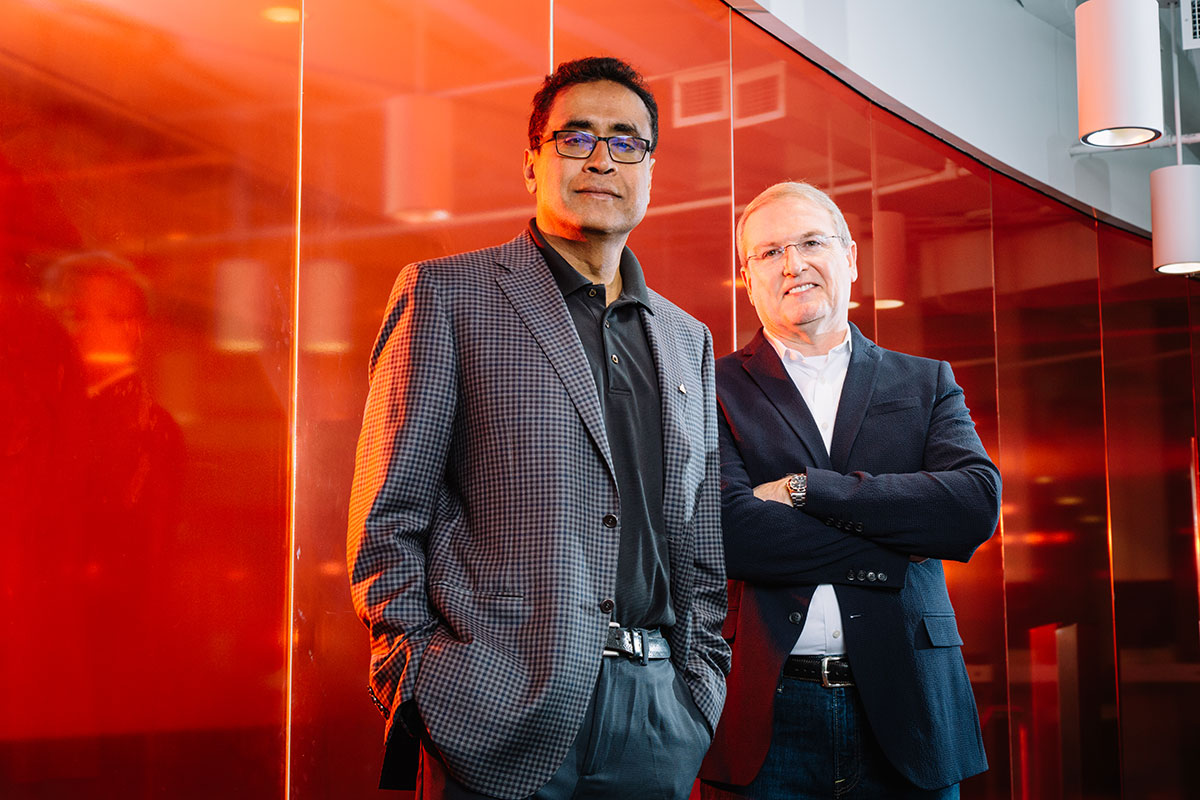

The key technology is a tooth microassay developed by Manish Arora, a professor of environmental medicine and public health and professor of dentistry at the Icahn School of Medicine of Mt. Sinai, New York.

“Teeth begin to develop at the end of the first trimester,” Brennan explains, “and grow in successive layers, like the rings on a tree.”

The microassay facilitates analysis of the composition of these individual growth layers on a week-by-week basis, enabling Arora to determine fetal exposure to environmental toxicants such as lead over time. Brennan believes the technique could also reveal markers associated with exposure to certain psychological events.

Since mothers take different medications during pregnancy, the tooth assay may also allow scientists to “look at the exposures of the medications and see the impact of those exposures on the fetus,” she adds.

Given the close proximity of teeth to the brain, it stands to reason that factors affecting teeth would also affect brain development, she says.

“We’re looking for the presence of stress and immune markers—cortisol, c-reactive protein, and interleukin-6, and heat-shock protein, which is a general stress marker.” The study builds on ongoing research that began in 2009 with mothers-to-be who were experiencing depression and stress during pregnancy and sought treatment through Emory’s Women’s Mental Health program. The women self-reported their stress levels at several points in time during pregnancy.

After participants’ children were born, Brennan continues, “we followed up on these kids as they were aging into preschool and elementary school to take measures of their stress reactivity and emotional reactivity to see if their psychological exposures in utero could be related to behavior problems later on.”

While initial results suggest a possible connection between maternal mental health and the brain development of some off spring, the tooth microassay establishes a definitive timeline for exposure and can provide more clear-cut answers.

Brennan is contacting those who either already have their kids’ baby teeth or expect to get them in the coming year and asking them to donate the teeth for analysis, which will be performed at Arora’s lab.

Fortunately, teeth don’t need to have been stored in any special way to be useful, she notes, but they do have to have fallen out naturally.

In the coming months, Brennan will examine the microassay data to establish the levels of fetal exposure to depression and stress, and also learn how closely the data aligns with the mothers’ psychological self-reporting.

She points out that even the microassay data itself is subject to some interpretation—and additional study.

“Fetuses have all kinds of protective mechanisms while they’re developing. Some placentas, perhaps because of their particular genetic makeup, may not let certain toxicants or exposures pass through. Or women who have had a stressful life in general may not have an extreme biological response to a particular event compared to someone who has not.”

Brennan’s hope is that the information and insights she gathers from “Out of the Mouths of Babes” will lead to improvements, as well as attention, on the mental health aspect of prenatal care.

“If, for example, we find that children’s outcomes are worse if they are exposed to stress or depression at some point during the second trimester, we could say that’s a particularly vulnerable period and design interventions targeting that time to help women deal better with stress,” she says, adding, “We have been fortunate to have an extremely dedicated group of moms and children who have been willing to share their time and personal experiences with depression and related symptoms.”