It's the Monster's Birthday: Celebrating Frankenstein at Two Hundred

Initially dismissed by critics as a gothic trifle, Mary Shelley's Frankenstein: Or, the Modern Prometheus is now a beloved classic and a cultural icon. The book, which turns two hundred this year, has never been out of print and remains one of the most read novels on US college campuses.

While Frankenstein is an early, groundbreaking example of science fiction, it cuts across genres. Major questions raised in its pages about science, society, and philosophy are still hotly debated.

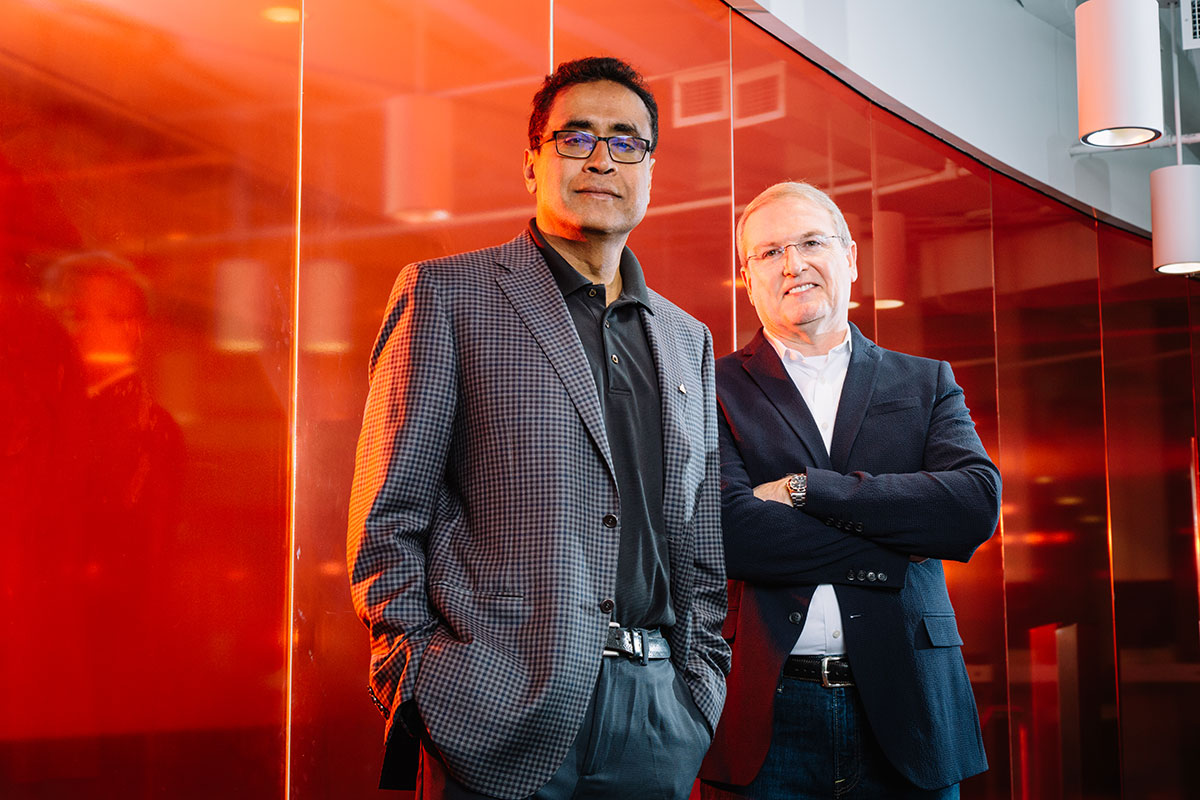

Emory faculty explore many of them in a newly published anthology, Frankenstein: How a Monster Became an Icon, the Science and Enduring Allure of Mary Shelley's Creation. The anthology is coedited by Sidney Perkowitz, Emory emeritus professor of physics, and Eddy Von Mueller, a former Emory lecturer in film studies who is now an independent filmmaker. They gathered chapters from seventeen experts across the country, including five from Emory, on different spheres of Frankenstein's influence.

"Frankenstein is one of the richest novels ever written," Perkowitz says. "It's full of important messages, such as there ought to be a way to make sure that science and technology work for the good of humanity, not the bad."

Perkowitz contributed a chapter in the anthology on how Frankenstein relates to the current quest for synthetic life. "When you see a contemporary film about androids, like Blade Runner 2049, you're seeing the Frankenstein story in a twenty-first-century guise," he says. "The androids are sleek and modern instead of the shambling, stitched-together creature in Frankenstein, but they have the same questions swirling around them. Even as we're on the verge of artificially generating life, we're no closer to knowing whether we should."

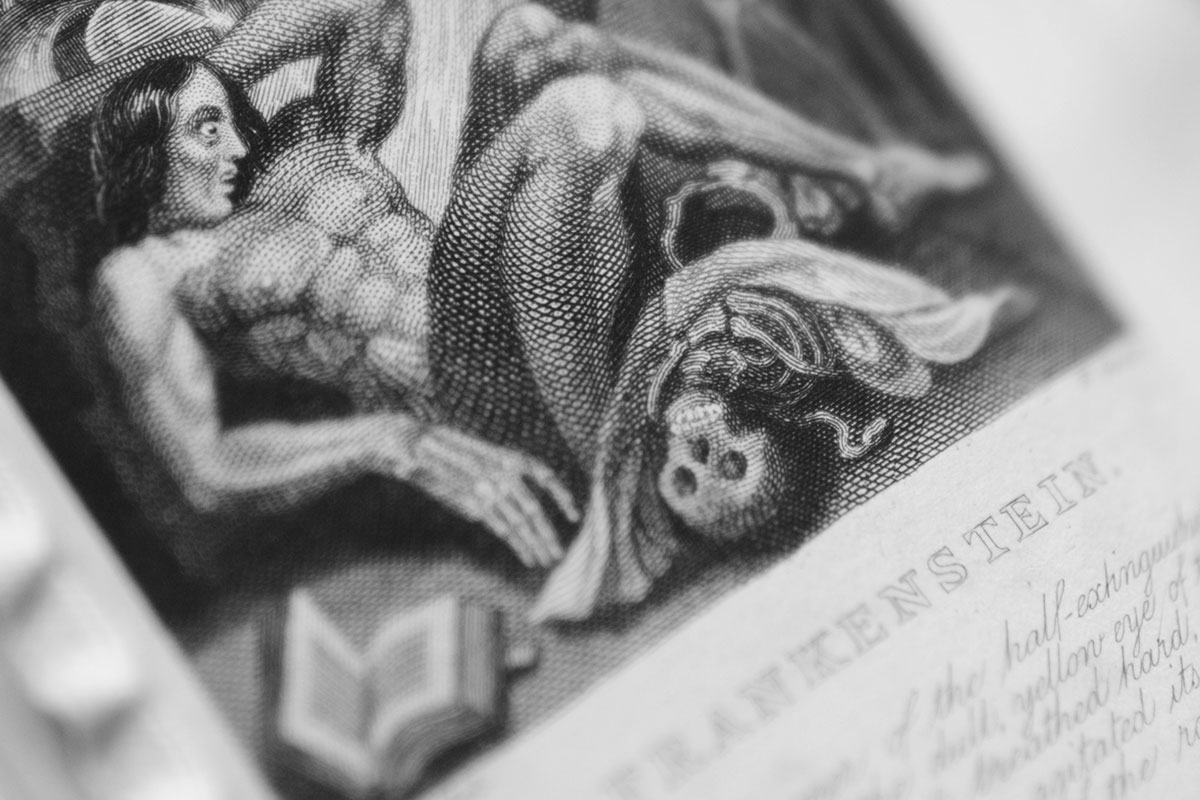

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley came of age during the Romantic era, when relatively new discoveries such as electricity ignited curiosity and the line between the humanities and the sciences had not been drawn, notes Courtney Chartier, head of research services for Emory's Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, which has an original edition of Frankenstein. Shelley's husband, the poet Percy Shelley, ran experiments in their home with an array of odd devices, such as what his friend and biographer Thomas Jefferson Hogg described as "an electrical apparatus." The poet would stand on the device and tell Hogg to crank up the machine "until he was filled with the fluid, so that his long, wild locks bristled and stood on end."

The couple was staying with friends in a villa in Italy when one member of the group—the poet Lord Byron—suggested that they have a competition to see who could write the best horror story.

Byron probably never suspected that the young Mary Shelley would win.

"She was just eighteen when she began writing Frankenstein," Perkowitz says. "As an Emory professor emeritus who has taught many exceptionally smart and creative students, I'm stunned that someone of college-freshman age produced this powerful work that has endured for two hundred years and still speaks to us today. That's almost more remarkable than the book itself."

That Face: Meet the haunting gaze of the creature as imagined for the 200th anniversary of his literary birth by artist Ross Rossin. If you fancy this face, you could look at it every day. A $50,000 gift from Turner Classic Movies is supporting Emory's Year of Frankenstein events and the Ethics and the Arts program, as well as the production of fine art prints of Rossin's depiction on cotton rag paper. The signed and numbered prints are $500, with all proceeds benefiting the Emory Center for Ethics.

Ross Rossin

The vigor and timeliness of the book is reflected in its myriad themes, from the first famous "deadbeat dad," in the form of the monster's creator Victor Frankenstein, to the religious and feminist overtones of a man trying to usurp the power of God and of women to create life on his own. Some see the book as a commentary on mistreatment of "the other," such as those with disabilities or anyone who differs from the mainstream.

"What was kind of delightful as we were talking to people from all these different disciplines to create the anthology is how Frankenstein becomes a meeting ground," Von Mueller told WABE in a recent interview. "It's really a nexus at which all of these distinctions dissolve, and we can come together to talk about this one story."