Lasting Impressions

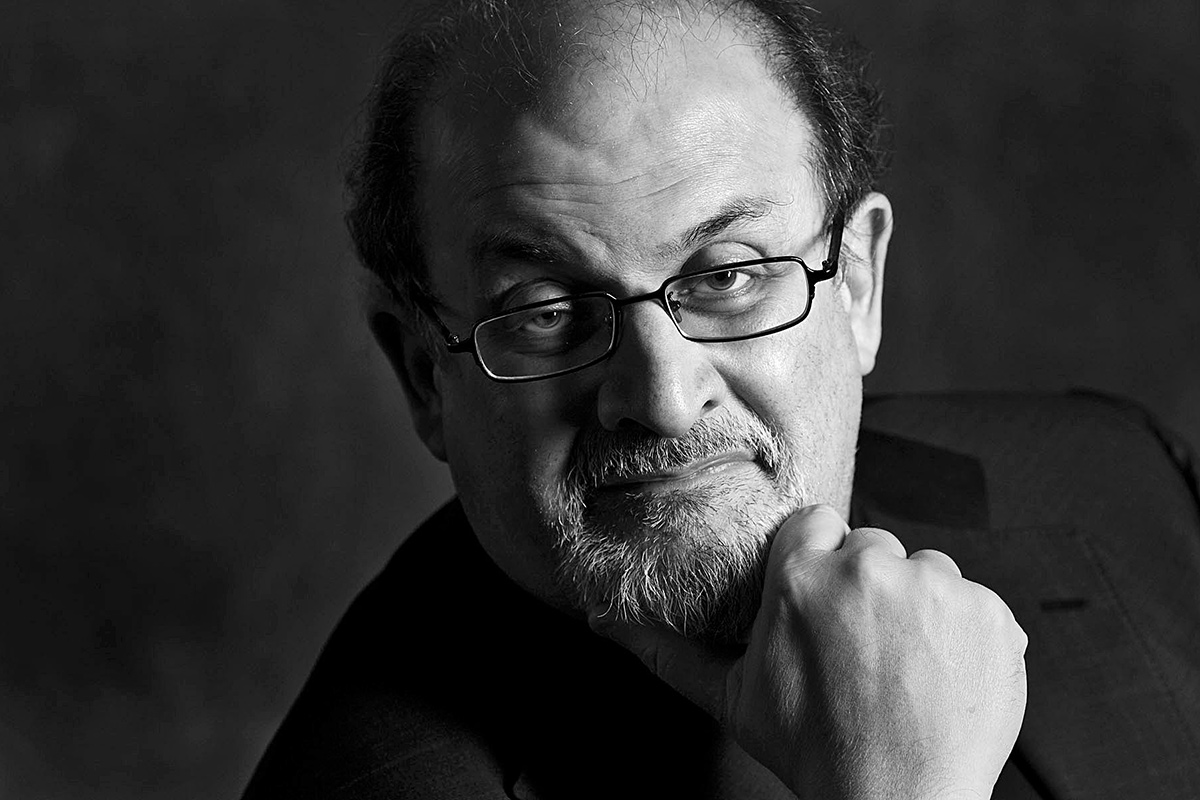

Salman Rushdie concludes his role as Distinguished Professor

Emory Photo/Video

Some might be surprised by what celebrated novelist Salman Rushdie calls his “very first literary influence”: the American classic film The Wizard of Oz.

The movie inspired ten-year-old Rushdie to write his first work of fiction—a fact he unexpectedly revealed in a classroom discussion during his final teaching visit as University Distinguished Professor in Emory College of Arts and Sciences in February.

Now lost to the ages, “Over the Rainbow” told the story of “a boy like me in a city like Bombay walking down the sidewalk and finding not the end of the rainbow, but the beginning of the rainbow,” arcing up like a staircase and leading to grand adventure, he said.

Amy Aidman, interim chair of Emory’s Department of Film and Media Studies, says Rushdie’s visit to her class was made richer by the fact that Rushdie is “amazingly knowledgeable about a vast number of topics and is willing to hypothesize and engage in a very interactive environment with students—to just see where the conversation goes.”

That intellectual dexterity, and a willingness to see where a classroom conversation takes him, has made Rushdie a popular speaker during his visits to Emory over the past decade. And like following the proverbial yellow brick road, students have been eager to see where the acclaimed author will lead them in the classroom.

From discussing the roots of his own writing in The Wizard of Oz to a somber discourse on the slums of Bombay, from exploring the intersection of disability rights and human rights to joining students for an impromptu read-through of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Rushdie’s annual campus visits have contributed to a legacy of unique learning opportunities.

Rushdie’s relationship with Emory stretches back to 2004, when the award–winning author was invited to present an address for the Richard Ellmann Lectures in Modern Literature series. That visit would lead Rushdie to find a permanent home for his papers in Emory’s Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL), a decision that he credits with helping him complete his autobiography, Joseph Anton: A Memoir.

As University Distinguished Professor in the Department of English, Rushdie would embrace the role of visiting scholar, lecturer, and colleague, engaging the campus community on a wide orbit of topics. But as he concludes his professorial role at Emory, it is Rushdie’s congenial and generous classroom presence that many will remember best.

“One of the most remarkable things about a conversation with Salman Rushdie, whether one-on-one or in a large group, is the sense of the personal,” says Coalition of the Liberal Arts (CoLA) Chair Robyn Fivush, associate vice provost of academic innovation and Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Psychology.

Watching Rushdie speak with faculty and staff at a CoLA conversation storytelling event, Fivush says she saw in him the embodiment of a true liberal arts scholar, both erudite and informed, with “an ability to speak across issues and disciplines in plain words that carry great meaning.”

“He is able to create an intellectual space that includes all of those in his presence,” she says. “His great joy in sharing ideas is palpable.”

For students, the CoLA event offered a rare glimpse at the man behind the book jacket. Hayley Silverstein 19C found Rushdie’s account of conflict with his father over choosing a college major both humanizing and encouraging.

“A lot of college students think about choosing a major as a way to make money, not choosing the major that you love,” Silverstein says. “It was nice to hear that you can choose a major that you love and still be successful in life.”

During his annual two-week teaching visits to Emory, Rushdie earned a reputation as something of an intellectual chameleon. One afternoon, he might be found discussing contemporary India with students in an advanced Hindi class or exploring the writing craft with select faculty members.

Another day, he’s chatting with undergraduates about the books that have been his greatest influences, or joining a roundtable discussion about human rights and human disabilities with Eva Kittay, Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at Stony Brook University and senior fellow of the Stony Brook Center for Medical Humanities, Compassionate Care, and Bioethics; English professor Benjamin Reiss; and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, professor of English and bioethics, who codirect Emory’s Disability Studies Initiative. (See related story, )

“If there are such a thing as rights, they must derive from human nature—those things which are in our nature to do as human beings,” Rushdie explained at the human rights forum. “You start with human nature, proceed through an idea of natural justice to human rights. I think that is true whether one is a disabled person or not. Start with the understanding of what we are as human beings.”

As a global citizen who has lived at the intersection of multiple cultures, Rushdie brought an accessible perspective to a vast range of classes and disciplines, says Gordon Newby, Goodrich C. White Professor of Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies.

“Students could talk with him not only about how he deals with those intersections, not only in terms of his literature, but in terms of his life,” Newby recalls. “He always offered a great intellectual flexibility and is very open about himself. And so it becomes a conversation, as opposed to a kind of traditional show-and-tell lecture—not everybody is able to pull that off, not all students are able to pull that off. But here, it worked.”

Looking back on Rushdie’s tenure at Emory, Newby says, “We can be pleased that he was a professor with us and that our students were up to the challenge of working with an educator of his caliber.”—Kimber Williams