Counting Days

This month, Emory celebrates the culmination of the academic year with Commencement. As days go, for universities, they don’t get much bigger: more than fifteen thousand people on the Quad, regalia and flowers and ties and high heels, four honorary degrees, well over four thousand diplomas conferred, countless cell phone snaps, and one Salman Rushdie sending graduates off into the future with words that no doubt will linger for years to come.

But it’s equally interesting to think about all the little days that led up to this big one. Four years ago, members of the Emory Class of 2015 were high school kids—studying for their final exams, planning their prom outfits, nervous and excited, texting and tweeting and posting, maybe applying for summer jobs or internships. During their time as Emory students, they studied, partied, called their parents, went on dates, worked out, cried, ordered pizza, stayed up all night with their friends, drank, laughed, and studied some more. They discovered things, learned things, made mistakes, figured stuff out. Most days.

Life is not made up of big days. It’s made up of most days, the ones filled with ordinary things. Coffee, email, meetings, Facebook, deadlines, exercise, dinner. All punctuated by the unrelenting demands of your mobile phone.

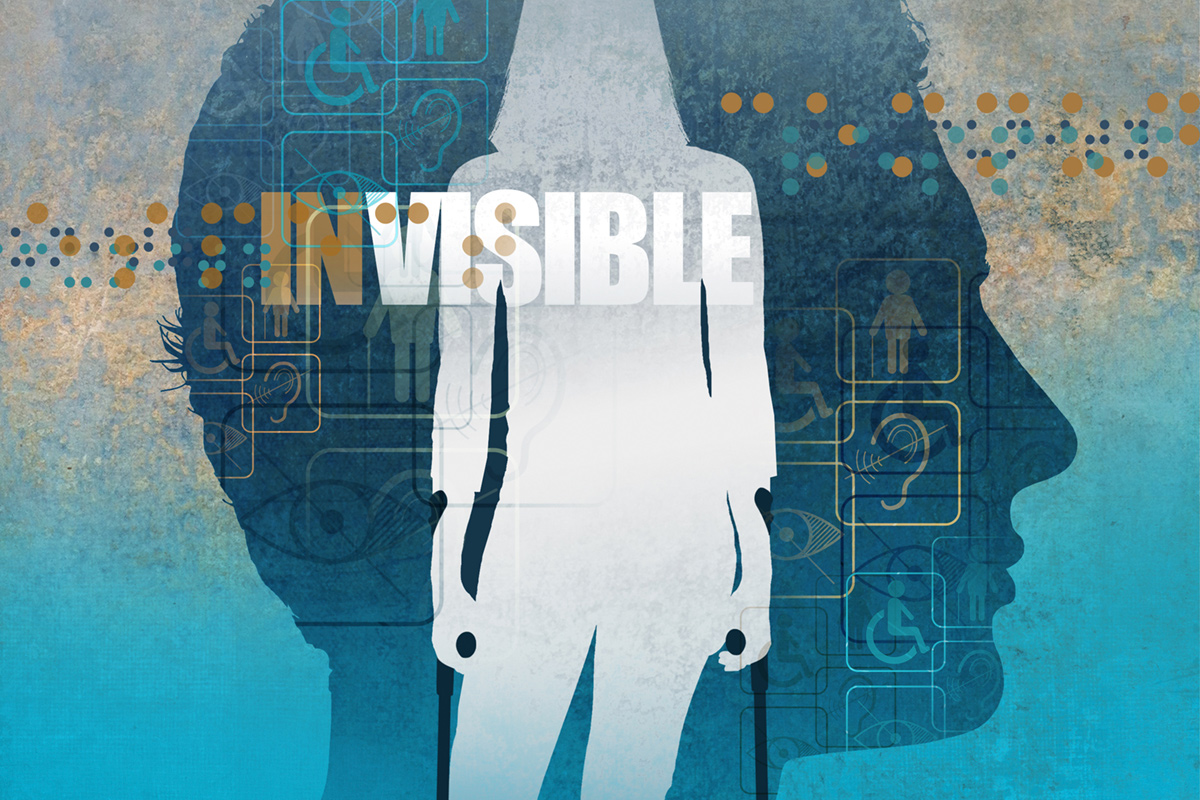

Everyone’s idea of a regular day is different. For some of the Emory community members spotlighted in this magazine, doing the everyday things that many of us take for granted—like typing an email, getting coffee, walking from the car to the office or classroom, finishing an assignment that’s due—is a little harder. That’s why the office of Access, Disability Services, and Resources is ramping up efforts to help Emory students and faculty members with disabilities have more of what most of us might consider ordinary days—days that are defined not by their disabilities and the challenges that accompany them, but by what they were able to accomplish.

Then there’s a regular day for an African American person living in the Jim Crow South. Emory’s class on the Georgia Cold Cases Project encourages students to dig deep into the history of civil rights–era crimes and uncover new, or hidden, facts about the victims’ stories. What they’re finding is that for blacks in 1950s and 1960s Georgia, most ordinary days were probably shadowed by some measure of fear; just walking down the street, buying lunch, driving one’s own car, going to school, or showing up for work could take an unexpected and, at times, tragic turn. But the discoveries of the Emory students are building on knowledge and fostering understanding for surviving generations.

For scientists and researchers, such as those working with the Emory-headquartered Center for Selective C-H Functionalization and Yerkes National Primate Research Center, a typical day could revolve around the arguably tedious process of lab work: analyzing, recording, retesting, resetting, and launching an experiment into motion yet again. Same for an artist like rising star Fahamu Pecou, who might spend a day experimenting with a new technique, medium, or source of inspiration. It takes a lot of little days to reach a big one—the breakthrough, lifesaving discovery or the truly great work of art.

My son will graduate from high school this month. Of course I’m looking forward to his graduation day, when our family and friends will celebrate the milestone with us, with pictures and tears and speeches. But this fall, when he joins the Emory Class of 2019 as an Oxford College freshman, I know it’s not his high school graduation day that I’ll miss.

It’s the ordinary days. Scrambled eggs and CNN, swapping yawns on the drive to school, arguing about homework, demonstrating how to fold laundry, asking if someone will please feed the dog, debating whether we should cook dinner or order pizza, laughing at the dog, yelling at the dog, debating whether the dog has been fed, watching The Walking Dead. Catching priceless, fleeting glimpses of the adult my kid will become—when he will make, and remake, his own definition of an ordinary day.

Most days are not big days. As it turns out, the small days are the ones that count. If you order pizza for dinner, please give some to the dog; he may or may not have

been fed.