More Than Just a Pretty Picture

A rising star in the art world, Fahamu Pecou has found an intellectual home as a doctoral student at Emory, pursuing studies that amplify his edgy creative work

Bryan Meltz

When Fahamu Pecou 16PhD was younger—before he had consciously claimed art as a means of self-expression and survival—he invented a superhero, a cartoon character named “Black Man.”

Armed with pencil and paper, Pecou found refuge in sketching the edgy adventures of Black Man, the alter ego of Ahmad, a brilliant young man whose father had died in an accident while trying to develop a molecular transformer. Sifting through his father’s notes, the grief-stricken character would discover a way to build the transformer himself—morphing into a superhero with superhuman qualities.

Super strong. Super smart. A skinny black kid with the power to save the world, who would rise up to become a great avenger of wrongs, battling crimes that resonated deep within the black community.

Back in Hartsville, South Carolina, where Pecou (pronounced “pay-coo”) sold his serialized comic strip for fifty cents an installment, high school friends teased that Ahmad looked suspiciously like the boy who had created him.

They were right.

“The character was based on me and the things I aspired to, that I hoped for,” acknowledges Pecou, an Atlanta-based visual and performing artist now pursuing doctoral studies at Emory’s Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts (ILA), whose critically acclaimed work has been exhibited in galleries from Paris to Panama, Switzerland to South Africa.

Even now, Pecou uses himself as a model, not in an autobiographical sense, he explains, but as an allegory, capturing traits “typically associated with black men in hip-hop and juxtaposing them within a fine art context . . . both the realities and fantasies projected from and onto black male bodies.”

Today, his artwork can be found displayed throughout notable public and private collections. Pecou has a much-anticipated exhibition and collaborative project on display at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art, on the heels of his first solo museum exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia (MOCA GA), which showcased some of his largest works to date. This summer, another show will open at the Backslash Gallery in Paris—by all measures, an artist on the ascent.

For Pecou, the journey—from a boy who once seized upon art as a refuge to a celebrated international artist noted for the shrewd cultural commentary that infuses his work—has been a jagged odyssey indeed.

The Black Walt Disney

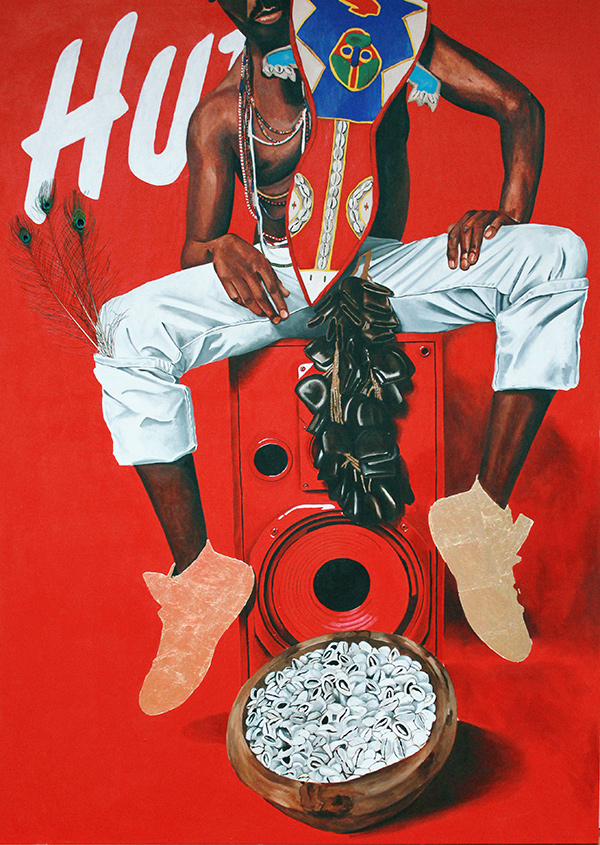

The public caught a glimpse of Pecou’s unique vision with GRAV•I•TY, the recent exhibit at MOCA GA and the culmination of his fellowship through the Working Artist Project, and in Imagining New Worlds, works inspired by the legacy of twentieth-century artist Wilfredo Lam, which opened in February at the High.

Both exhibits showcase bold, culturally engaged art with an unexpected twist. In Imagining New Worlds, Pecou combines aspects of modern hip-hop imagery with his own interest in Yoruba, spiritually rooted in African culture, and Négritude—the midcentury movement by black Francophone intellectuals to create a black identity separate from that of their French colonizers.

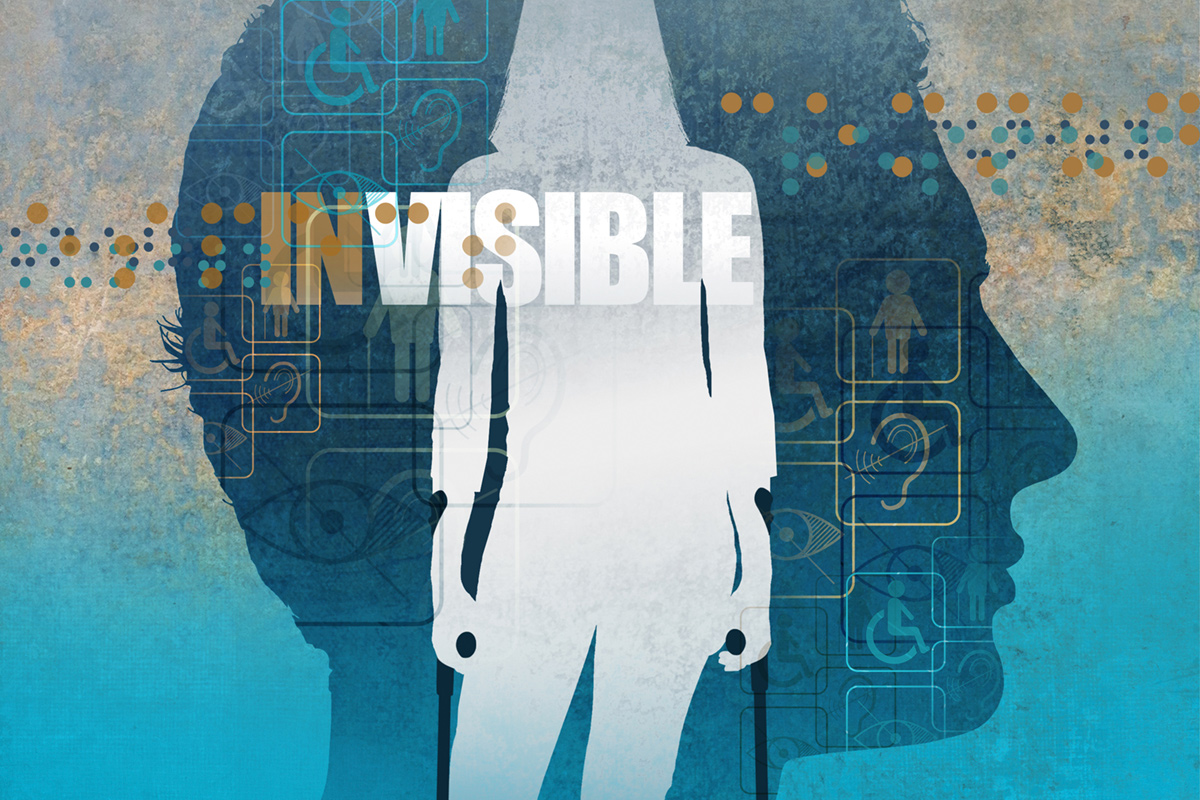

Through a series of drawings, paintings, language, and soundworks, GRAV•I•TY embodied a clever triple entendre, exploring not only a physical concept and the sense of something serious, but also the controversial trend of “saggin’ ”—a low-riding style of wearing pants that puts boxer shorts on full display.

The exhibit was informed by Pecou’s broader research into contemporary representations of black masculinity in popular culture—one focus of his studies at Emory. Like other forms of resistance in marginalized communities, oppositional fashion trends like saggin’ can serve as a politicized statement, “a demand to be recognized in a world that wishes to render you invisible.”

He knows what it is like to feel invisible. Much of his childhood was shaped by a complex search for identity. Born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1975, Pecou was only four years old the night his father, who had long battled schizophrenia, murdered his mother.

As Pecou and his three siblings watched television, his mother, Betty Ann, attended to his father, Alphonso, who had tried and failed to have himself committed for psychiatric care earlier that day. Their angry shouts shook the apartment; then, a shattering scream.

Alphonso barked at the children to prepare to run. When the door to their bedroom swung open, young Fahamu thought he could see bright-hot flames dancing within.

It would be years before Pecou allowed himself to confront the full memory of that night. After his father turned himself in at a local police precinct, Pecou and his siblings were sent to South Carolina to live in a public housing project with his mother’s relatives.

Aunt Punch, as she was called, was as good as her nickname. She had no patience for a sensitive boy who liked to sketch the cartoons he saw on television, who enjoyed school and won art contests and could lose himself in an encyclopedia.

And so it was that Pecou invented Black Man—the superhuman boy who stood strong against his enemies. “Art was my saving grace, my go-to place when things got a little rough,” he recalls.

Pecou was nine years old when he discovered what a cartoon animator was, reading about the profession in an encyclopedia. “From that moment until the time I got to college, it became my singular focus,” he says. “I told my friends that I was going to be the black Walt Disney.”

Life after Death

During Pecou’s first class at Atlanta College of Art, an instructor scratched the words, “What Is Art?” on the blackboard.

To Pecou, “it was just something that I did.” Hesitant to enter the conversation, he said nothing. But the question would haunt him.

During his freshman year, a friend insisted that there was more to art than the cartoons he labored over. He remembers her “dragging me by the hand to the High Museum of Art,” his first trip to a museum or gallery. “It blew my mind,” Pecou recalls.

“I saw a different potential for myself as an artist,” he explains. “I started painting more and ultimately changed my major from animation to painting. There was something about it that made me feel more alive.”

In time, Pecou was creating paintings of his cartoon characters, wryly imposing his superheroes onto the covers of popular magazines, such as Ebony or Essence. While taking an independent study class at Spelman College, his work caught the eye of Arturo Lindsay, an artist-scholar known for ethnographic research on African aesthetics in contemporary American culture, who christened Pecou’s work “Neo-Pop.”

When Lindsay challenged him to create on a larger scale, Pecou produced six-foot-tall canvases of the magazine covers, wrestling with them during MARTA commutes. Art was taking on new possibilities, and with it, Pecou found himself in search of deeper meaning.

One night during his junior year, a fellow art student who worked with found objects stopped by Pecou’s room. From a construction site, he had salvaged a battered, wooden box—an old cement mold. “There was something about it that resonated within me,” Pecou recalls.

Later that night, listening to a Goodie Mob song, “Guess Who,” the lyrics spoke to him anew: “There will never be another that will love me like my mother . . . ”

“I must have listened to it on replay for hours,” he says. “When I came out of my fog, I had transformed that battered cement mold into a spirit box, a tribute to my mom. It was powerful for me in ways I could not explain, motivated me for the first time to really engage with the story of my mom and my family.”

As if by collective agreement, Pecou, his brother, and sisters had never spoken of the night their mother died, stabbed in the chest with a machete. Closing his eyes, Pecou could summon fragments, but was never sure if they were only dreams.

Inspired, he interviewed his siblings, reawakening their own splintered impressions—fleeing the apartment, bloodstains on their father’s shirt, and a cold walk to the police station, where his father announced that he was “Jesus Christ” and had just “killed the devil.”

From those excavated memories, Pecou would create Life after Death, a senior project that laid bare the turbulent love, pain, and truth of his own past.

The experience was transformative.

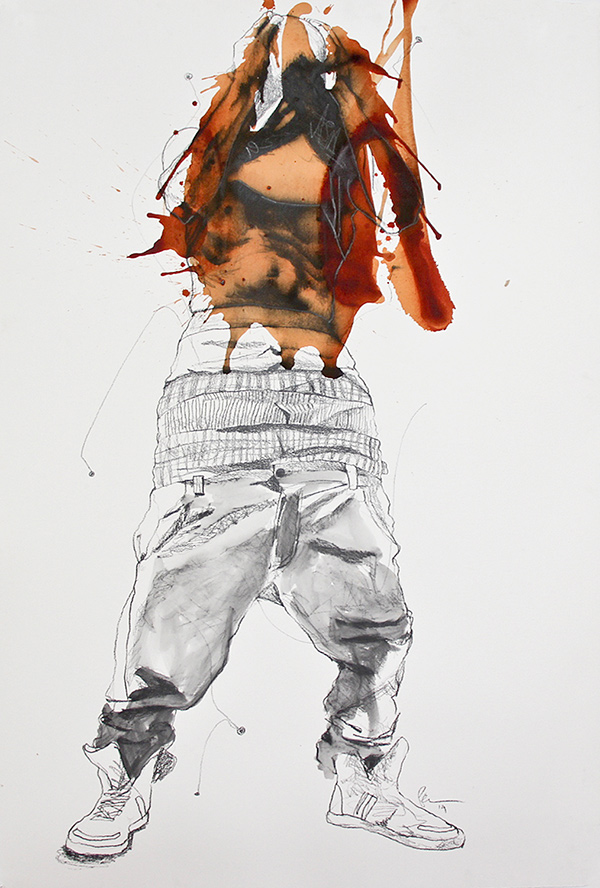

Head Rush, 2014, acrylic and graphite on paper.

“When that exhibition opened I was a little nervous, because it was very personal,” Pecou recalls. “People walked in and their faces opened, glistening with tears. Some were so moved they shared with me incidents of their own childhood tragedy. My work gave them the courage to face things they had shied away from.”

“From that point on, I decided never to make art for the sake of making a pretty picture, but to move people and change the world,” he says.

After such a dynamic debut, the years that followed were a creative struggle.

Following graduation in 1997, he “lied his way into a graphic design job” at a small, boutique agency in New York, working with rising performers, nightclubs, and restaurants. Noting how different rappers often were from the personas they projected, Pecou wondered: Why doesn’t someone market a visual artist the way we do a rapper?

The question drew him back to Atlanta, where he joined a friend to create a new design firm, Diamond Lounge Studios. They sought clients door-to-door, hitting up clubs and studios with a growing portfolio of hip, urban material.

At the same time, Pecou was trying to get his own artwork into galleries, with little success.

In 2001, Pecou had an opportunity to do work for former Atlanta Mayor Shirley Jackson’s inaugural campaign. Soon, Pecou and his partner shared a running joke—in order to get into art galleries, he would need his own election committee.

Beneath the sarcasm, Pecou saw some truth. Building upon his own ideas about marketing visual artists, the young artist decided to create a brash, tongue-in-cheek underground campaign: “Fahamu Pecou Is The S--t,” paid for by the Committee to Officially Make Fahamu Pecou the S--t.

It was a subversive experiment, a parody of a promotional campaign “with no rhyme or reason,” Pecou admits. “And it was a hit.”

As the slogan, along with a graphic image of a tough, shirtless Pecou, began to appear on fliers, stickers, T-shirts, and a viral email campaign throughout Atlanta, the buzz began to build: Who was this Fahamu Pecou?

Pecou took it a step further, inserting his image on a fake magazine cover, which he printed on a reader response card; those who returned the card would receive a free copy of the magazine. When Pecou slipped the cards into real magazines on newsstands, hundreds were mailed back.

Painting that magazine cover was more than an elaborate joke. It also kindled his creativity, resulting in the creation of NEOPOP, a series of paintings that played on celebrity, hip-hop, and culture. His artistic rhythm was back. In 2004, Pecou was invited to join Art, Beats and Lyrics, a group art show at the High Museum of Art.

In the past, Pecou had walked door-to-door seeking art galleries to show his work, save one—the Ty Stokes Gallery, located directly across the street from his own Diamond Lounge Studio in Atlanta’s Castleberry Hill Art District. As neighbors, Pecou had frequently chatted over coffee with gallery owner Bill Bounds, but never to trumpet his own art. Stepping into Pecou’s studio to retrieve a Pecou T-shirt, the gallery owner noticed the bold NEOPOP canvases leaning against the walls.

He stood motionless, studying them. “You should put these in my gallery,” Bounds finally said.

From Boyhood to Manhood

Soul Power, 2015, acrylic gold leaf and peacock feathers on canvas.

The opening of the High Museum exhibit marked a grand debut for the Fahamu Pecou character—a victory lap of sorts, and the culmination of his satirical publicity campaign.

Pecou made it a night to remember, playing up his growing urban mystique with swaggy celebrity regalia, including a six-foot-eight-inch bodyguard, a pretty girl draped on his arm, and a small entourage. He turned the promotional game on its ear—both used it and mocked it—and he won. Not long after that, things began to snowball.

When Pecou’s work went up in the Ty Stokes Gallery, Bounds shared images with a friend who ran a gallery in Dallas, Texas, who immediately wanted to show the work, too.

The Dallas show, NEOPOP Goes the World, sold out before it ever opened. Paintings were still in bubble wrap leaning against the walls “and people were coming in, pointing and saying, ‘I’ll take that one,’” Pecou recalls.

Over the next few years, Pecou’s work would be featured in more than a dozen group shows or exhibits. Paintings that he’d once struggled to sell for $100 were suddenly fetching thousands of dollars. Interest in his bold, urban work and challenging viewpoint was spreading.

But it was the birth of his children, daughter Oji and son Ngozi, that would bring him to a deeper, more introspective place. “I began to think about my own journey from boyhood to manhood—not having a father around had affected me,” he explains. “I wanted to use my work to have a broader conversation with young black men about their identity, their masculinity, some of the inherited and imposed expectations that young black men face.”

The Artist as Scholar (or, Fahamu Mania)

Although Pecou likes to think his work has always radiated deeper meaning, in light of events such as the Michael Brown shooting in Ferguson, Missouri, its themes have taken on new urgency.

“I shifted from NEOPOP celebrity to really looking at black masculinity and how it could be influenced with various representations,” he says.

It’s a focus also reflected in Pecou’s work at Emory, where he’s now in his third year of graduate studies at the ILA. Though research has always been a part of his art, Pecou says he came to the university driven by “a deep yearning to be challenged in an intellectual environment.”

Pecou recalls venting his frustration one night at “Yo! Karaoke,” a local karaoke event he helped host at Pal’s Lounge on Auburn Avenue. “I wanted to go back to school, but couldn’t find a program to suit my needs,” Pecou recalls telling his friend and fellow karaoke disciple Michael Leo Owens, who happens to work at Emory.

Owens, an associate professor of political science, suggested the interdisciplinary flexibility offered in Emory’s ILA would be a good fit.

“Everyone who knows Fahamu knows that he’s a true Renaissance man,” Owens says. “He has an incredible set of talents—it seems there’s nothing he can’t do or won’t try, and he’s successful at it all.”

What his art invites, Owens says, “is a really nice, long conversation and critique about not only black culture, but American culture, along with the potential to help young black men and women to believe there is a greater, broader set of opportunities available to them.”

Pecou attended an ILA open house at Emory and quickly submitted an application, complete with samples of his art, recalls Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, associate professor in African American studies and director of graduate studies in ILA, who would become his adviser.

“We were all fighting over his application,” Wallace-Sanders laughs. “It was our first introduction to Fahamu mania.”

As a student, Wallace-Sanders has found Pecou “open to everything I can throw at him, from feminist theory to philosophy—he’s always thinking of ways to add another layer of meaning to his art, always thinking about the right questions to ask.”

“I can’t tell you what it’s like to witness his mind at work,” she says. “He’ll show me something on a sketchpad, then on a computer, then it’s a conversation, then it’s on a canvas, then he’s flying off somewhere to present a paper about it.”

Pecou says his academic experience has “freed my work. I find that I can address some of the concerns and ideas I have academically, which amplifies my art.”

The scholarship and artistry often work hand in hand. Pecou expanded upon themes from his GRAV•I•TY exhibit to write a research paper that he will present at the international conference “Black Portraiture(s) II: Imagining the Black Body and Restaging Histories” in Florence, Italy, later this spring.

At times, it’s hard to tell where one discipline ends and the other begins. Working in Emory’s Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library to help catalog the library of the late Emory professor Rudolph Byrd introduced Pecou to early twentieth-century magazines he’d never before discovered. That influence can be seen in his Imagining New Worlds exhibit at the High Museum. One of his paintings depicts a stylized self-portrait on the cover of Negro Digest, a magazine originally published in the 1940s as an alternative to Reader’s Digest.

Through his studies at Emory, Pecou has been able to engage with leading theorists around “black masculinity, hip-hop theory—all of these viewpoints coming together that have allowed me to really think through my own ideas.”

“I can talk to a kid on the street about saggin’ or a room full of scholars about oppositional fashion and have them understand the same message,” he adds. “I think that’s really powerful.”