InVisible

Illuminating disability, inside the classroom and out

If you are fortunate enough to receive an email from Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, Emory professor of English and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, you will no doubt note this caveat beneath her signature:

“Because this message was composed using dictation rather than keyboarding, it probably contains distinctive mistakes. Dictation never misspells, but it frequently uses the wrong words and misspells names. Thank you in advance for reading creatively, considering the larger context when my words are confusing or hilarious, and tolerating missing salutations and random capitalizations.”

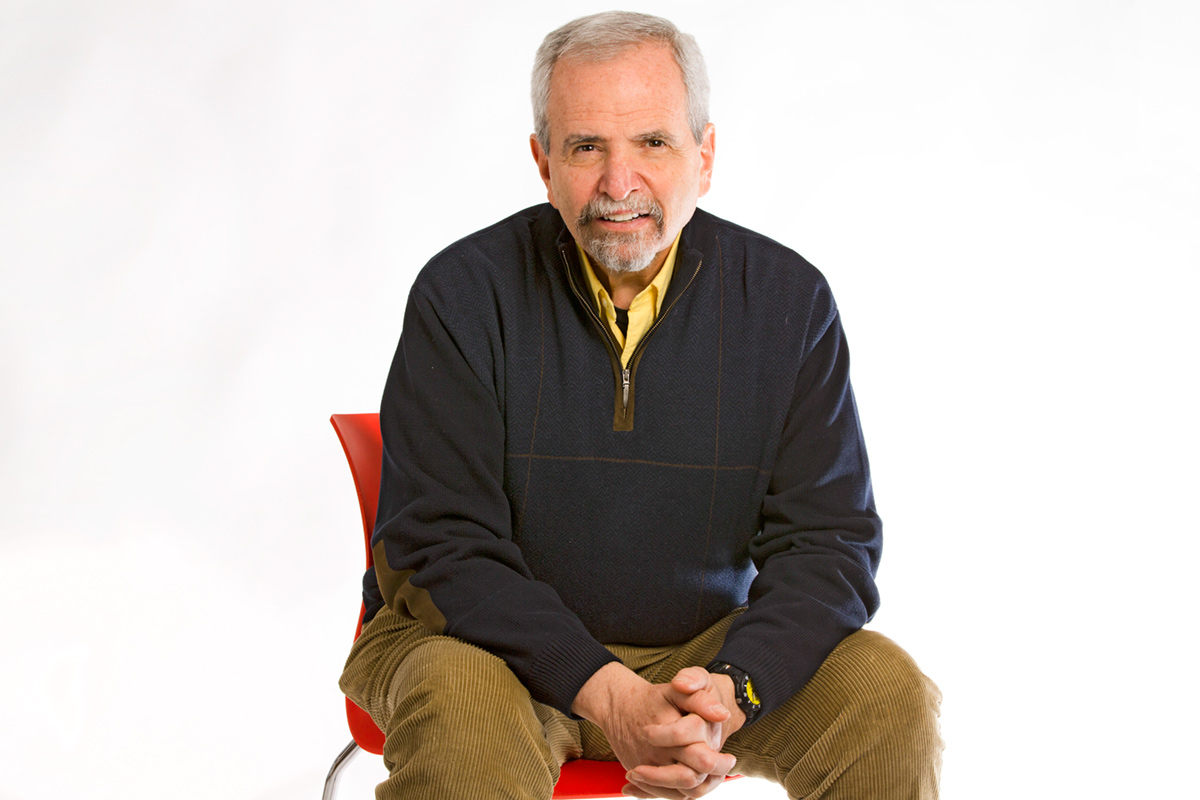

That sort of wry, intelligent, here-I-am humor is typical of Garland-Thomson, who was born with a total of six fingers and one arm that is half the length of the other and does not type. In the emerging academic field of disability studies, where much of her scholarship is focused, she is something of a rock star.

Garland-Thomson has many titles. One of the more recent is codirector of the Disability Studies Initiative (DSI) at Emory, a broad-based program created in 2013 to spotlight and support the study of disability. Garland-Thomson leads the initiative with Benjamin Reiss, a fellow professor of English whose research focuses on connections between literature, medicine, and disability in nineteenth-century American culture.

The DSI is at the forefront of a national, interdisciplinary movement that builds on wide-ranging academic research to challenge assumptions about human difference and shared definitions of life well and fully lived. One of the objectives, says Garland-Thomson, is to expand the umbrella known as “diversity studies” to encompass variations in physical, sensory, and cognitive ability, as well as other kinds of identity.

“Although much recent scholarship explores how difference and identity operate in such politicized constructions as gender, race, and sexuality, cultural and literary criticism has generally overlooked the related perceptions of corporeal otherness we think of variously as ‘monstrosity,’ ‘mutilation,’ ‘deformation,’ ‘crippledness,’ or ‘physical disability,’ ” she writes in the first chapter of her seminal 1997 book Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. “Yet the physically extraordinary figure these terms describe is as essential to the cultural project of American self-making as the varied throng of gendered, racial, ethnic, and sexual figures of otherness that support the privileged norm.” The book is one of five that Garland-Thomson has written, edited, or co-edited; she also is currently pursuing a master’s degree in bioethics at Emory.

Rosemarie Garland-Thomson

Interest at Emory is spreading across disciplines. From literary and cultural portrayals to medical ethics and theology, a range of research was on display in the second Disability Scholars Showcase in November, where five scholars presented overviews of their works in progress as they relate to the study of disability in their fields. Two scholars with backgrounds in literature discussed how ideas about disability become encoded in different cultural systems. On the other side of the spectrum, applied disability studies were highlighted by a neonatologist and a neuroethics scholar, who discussed the ethics involved in diagnosing conditions like autism or genetic anomalies and how they are presented to patients and their families. And a religion scholar is exploring how an Atlanta church is making new meaning, narrative, and symbolism by including people with mental illness.

In his introduction, Reiss noted the diversity of the projects presented. “One of the best things is simply people saying, ‘I had no idea that somebody over in this part of the university is doing something that’s connected to what I’m doing’, ” he said.

This year marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), enacted in 1990 to prevent discrimination and require reasonable accommodations for disabled people. Since then, fixtures such as curb cuts, access ramps, reserved parking spaces, and automatic doors have become commonplace in public spaces; but as Garland-Thomson points out, it’s easy to overlook the fact that those accessibility features serve everyone, not just people with disabilities.

“The disability rights movement created a transformation of the built environment that had the unintended benefit of creating diversity inclusion and equity for other groups—the elderly, caregivers of small children, transgendered people, travelers,” she says. “A federal mandate has led to a more inclusive world for everyone. That’s the whole point of disability studies. I believe that the development of big strollers and wheeled suitcases was made possible by the ramping of the world.”

The ADA also helped lead to a dramatic expansion of the meaning of disability, which now includes conditions such as attention deficit disorder (the most common at Emory and on most college campuses), autism spectrum disorders, forms of psychiatric disability such as depression, learning disabilities, asthma and allergies, and a range of neurological differences known as “neurodiversity.”

Many of the fifty-plus Emory community members involved in the DSI do not identify themselves as disabled. One is Joel Michael Reynolds 16PhD, a graduate student in the Department of Philosophy, Laney Graduate School Disability Studies Fellow, and DSI program coordinator, whose mother and late brother are disabled (see his essay on page 68). While pursuing his doctoral research on how concepts of ability and disability affect ethical theorizing—concepts that have historically led to misperceptions about quality of life for people with disabilities—Reynolds also sends out weekly updates to the DSI email list promoting a startling array of events, speakers, meetings, performances, and opportunities to participate in academic projects. A recent message invited DSI followers to hear a guest lecture about disability and aesthetics, attend a seminar on deafness and universal design, join a dance class for all body types, and participate in two different research studies (one creating a smartphone app for wheelchair users).

“Medical professionals tend to understand disabilities as individual tragedies,” Reynolds says. “What’s so exciting about the DSI is that it examines disability as a concept, a subject worthy of exploration and dialogue. The point is not that Emory is doing everything right, but that Emory is engaged in these questions, socially and academically.”

Many would agree that while the Disability Studies Initiative and related efforts put Emory at the leading edge of the field, the day-to-day reality for people with disabilities on the Emory campus has not always kept pace with their needs. Lynell Cadray, associate vice provost in the Office of Equity and Inclusion, says that as the number of students, faculty, and staff who identify as disabled has increased, so have the responsibilities of the disability services team, now called Access, Disability Services, and Resources (ADSR). The office is in the process of developing a strategic plan that includes a community survey, staff training, better automation of information, and improved customer service and academic support.

“I’m very optimistic that the work we are undertaking will benefit the entire university,” Cadray says. “We want to be more than compliant—we want to do the right things for our community.”

The person charged with implementing these efforts is Allison Butler, new ADSR director and ADA compliance officer, who came to Emory in April from the University of Maryland University College. With fifteen years’ experience in disability services, Butler has been reaching out to all areas of the Emory campus to build a network of support, advocacy, and expertise.

Some of the most common needs of Emory students with disabilities include extended time for supervised test-taking, assistance with note-taking in the classroom, and accessible instructional materials; Butler says she is working to strengthen the policies and procedures around all these services. Her broader vision for Emory is focused on applying the principles of universal design—a movement founded on the idea that the physical environment should be accessible to everyone. Much like Garland-Thomson’s push to position disability studies within the broader field of diversity scholarship, Butler’s interest in universal design represents a shift toward viewing the campus as one community with a wide range of abilities, rather than separating the needs of people with disabilities.

Universal design has expanded to areas beyond architecture; for instance, at Emory, it might call for a more deliberate integration of disability services with academic resources, such as classroom technology that benefits all students.

“I am thinking about compliance and access at a macro level,” Butler says. “Universal design is a broad concept that can guide all our decisions across all areas of the university. At the same time, I want our approach to students to be very individualized. There is their diagnosis, and then there is what they really need to be successful here.”

Unlimited: Voices from the Community

Leslie S. Leighton 15PhD, graduate student and graduate instructor

Progressive neuromuscular disease (muscular dystrophy)

What I Do

No longer able to practice medicine as a physician because of profound muscle weakness, fatigue, and the inability to ambulate well, I decided to pursue other educational opportunities and ultimately a PhD in the history of medicine in the Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts at Emory. My disability has limited my ability to walk and climb stairs but not to do scholarly work, research, and learn. I became very interested in the history of coronary heart disease (CHD) as a graduate student, and my research and dissertation are directed at elaborating the specific reason for the initial decline in CHD mortality that occurred in this country in the late 1960s. Accommodations made for me through the Office of Access, Disability Services, and Resources (formerly ODS) have made it possible for me to study at Emory and pursue my educational goals. Without their help, this would not have been possible.

How I Do It

I arrive on campus in the morning and have designated parking close to the library and my academic department. I ambulate around the campus with the use of crutches and the shuttle bus system. Emory has provided me with parking on campus and the Cliff bus system helps me get around from building to building as walking is very difficult.

Day to Day

Emory is a hilly campus, so getting around on foot for an individual with a physical disability can be difficult at best, and often just impossible. I was having particular difficulty getting in and out of the Woodruff Library, so I went to the library administration office to see if I could get special access to the rear door of the library—which has somewhat easier access to the shuttle buses—but the library could not grant me access to use the rear door for liability reasons. The disability office, however, provided me with designated parking that made access to the library for my research possible.

Graduating from Emory appeared to be very daunting for me. I all but decided not to participate in Commencement exercises because I felt it was going to be too difficult for me to keep up with much younger able-bodied graduates in line and also to ascend stairs. I contacted the Laney Graduate School and told them that I did not think I could participate in Commencement exercises because of my disability. They arranged for me to have special access, without stairs, to the ceremony and a special chair from which I could stand much more easily. They would not hear of my disability limiting my participation in Commencement, and they made it happen for me. I will be able to participate in graduation with special accommodations, and am grateful to the staff of the Laney Graduate School for their assistance in this endeavor.

Anna Hull 16T, master of theological studies candidate

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, a degenerative, genetic connective-tissue disorder

What I Do

I chose to pursue a masters in theological studies because of my interest in how spirituality affects medical decisions. I am currently applying to the bioethics program as well, and I hope to eventually work in the field of medical ethics for a hospital while also serving as a chaplain who is able to discuss medical decisions with patients and help them make choices congruent with their own beliefs. My interests largely stemmed from my own medical issues and the disconnect between these two fields that I have witnessed as I have been in and out of hospitals.

How I Do It

Living with a disability often takes a great deal of intentionality. For me, that plays out in every area of my life at Emory, from arriving on campus with ample time before class because I do not know if there will be any open handicapped parking near my building to the way that I carefully plan out everything that goes into my bag so that I am not carrying any additional weight, which could throw off my balance with crutches or cause my shoulder to sublux or dislocate when I take my bag off and on. It can mean knowing what floors have bathrooms with door openers when I am using my wheelchair and which hills are steep enough to cause a wheelchair to flip.

Day to Day

Living with a degenerative illness is challenging, as you must constantly adjust to a new “normal,” which can make comfort in and acceptance of your own body difficult. Last fall I marched with Emory in the Atlanta Pride parade, but had to use my wheelchair, something still new to me. At one point along the route, I saw a little girl in a wheelchair watching the parade. When she saw me, she became so excited and was practically bouncing up and down, waving enthusiastically while pointing me out to her parents. I am pretty sure that I was just as excited waving back at her as it was a moment when neither one of us was being made to feel different or “othered” because our bodies are different. One of the most challenging things for me in relation to my disability is when others take on an identity of being victimized by it. If I don’t feel like a victim in my own body, chances are, you’re not a victim of my body either.

Adam P. Newman 17PhD, doctoral candidate in the Department of English

Fibromyalgia, a chronic illness that entails widespread chronic pain and fatigue; depression; and a two-time brain tumor survivor

What I Do

I am a George W. Woodruff Fellow in the Department of English, and my research fields broadly defined include nineteenth- and twentieth-century American and African American literature and culture and disability studies. Currently I am writing a dissertation about the ways race and disability have been thought about in relation to each other, particularly in literary representations of dependency and care that involve individuals of one race caring for individuals of another race.

How I Do It

Dealing with a chronic condition like fibromyalgia—which can flare up quite unexpectedly in relation to things like weather changes—means I have to have a much more flexible routine than many others, as I just don’t know how I will feel one day to the next and thus need to adapt each day to how much energy I have. I ascribe much of my continued success to the flexibility that academia has allowed me in terms of self-accommodation. The biggest accommodation that Emory has made for my disability is in regard to my comprehensive exams, which graduate students in my department take in their third year. For the written examination, over a period of seventy-two hours, students have to write three ten-page papers in response to questions posed by their committee members. But since my energy and abilities can vary quite unexpectedly day to day, my department and the graduate school allowed me to have an extra twenty-four hours for my written exams, which then allowed me to have wiggle room in case I had a flare-up on one of those original three days. While I had to actively advocate for such an accommodation, I give the university a lot of credit for recognizing the importance of such an accommodation for my continued success.

Day to Day

Because of my disabilities, I have had the incredible fortune in the past decade to become a member of a number of incredibly invigorating social, political, and intellectual communities of people with disabilities and those thinking critically about disabilities. Whether it is the DSI here at Emory, or the national Society for Disability Studies, or the Children’s Brain Tumor Foundation, these various communities—which I never would have even known about, let alone become a member of, if not for my disabilities—have facilitated some of my most powerful friendships, influential professional relationships, and happiest memories.

Catherine Howett Smith 84C 99G, Staff member since 1985; associate director, Michael C. Carlos Museum

Progressive neuromuscular disease

What I Do

I have a graduate degree in art history and attended the Getty Museum Management Institute at UC–Berkeley. I am associate director of the Michael C. Carlos Museum. Since most of my work uses my brain, rather than my body, I can excel in spite of my disability. My greatest obstacle is not being able to visit donors at their homes or attend events held in patrons’ houses because private residences are rarely handicap accessible. I feel somewhat confined to the accessible environment I’ve made for myself at my home and in my office.

How I Do It

I am able to work a flexible schedule as needed in order to manage the pain and fatigue associated with my disability, and I telecommute one day a week. My building is accessible to me, but when I need to attend meetings in other spaces, go to lunch, or visit a colleague, I often encounter barriers such as vehicles blocking curb cuts, inaccessible bathrooms, able-bodied people using the only accessible bathroom stall instead of the other choices they have, inaccessible salad bars, broken electronic door openers, etc. I’m always looking for the back door, the side door, or the special entrance while everyone else goes in the front entrance. My hope is that the world will someday embrace and implement the idea of universal design, not only in public buildings, but also in private residences, so that everyone can participate in the life of the community with dignity.

Day to Day

I have had many difficult experiences with accessibility. One occurred in 2007. I was a former chair of the President’s Commission on the Status of Women and was invited to an anniversary recognition ceremony to be held at Beckham Grove, which had recently been built outside Woodruff Library. I arrived to discover that this newly built space was completely inaccessible. I left the event and missed the ceremony; I felt excluded. The next day I reported the problem to the appropriate university department. They removed a section of the landscaping chain to open a path through the grass at the back, but rolling a wheelchair over thick grass and mud is not the kind of physical access that makes that space welcoming to everyone. I was shocked that accessibility was not considered so many years after we were legally required to provide access.

A positive experience I had was when I was a senior at Emory College in 1984. I had struggled so much with physical issues and accessibility in college and wanted to share my experience before I left so that things could hopefully be improved. I wrote a letter to then-President Jim Laney. Much to my surprise, he called me and invited me to come talk to him. We sat in his office for hours discussing my love for Emory as well as my experiences and challenges. Dr. Laney made me feel valued, and I felt that I had been heard.