To Win but Barely Place

A biography by an ex-NFL player celebrates an African American jockey in postbellum America

Kay Hinton

If you are shocked to know that African American jockeys existed—much less thrived—in nineteenth-century America, don’t tell Pellom McDaniels III. He will be shocked that you are shocked. And yet, in the end, he accepts that his job is to ensure that our shared national history is just that.

McDaniels—the faculty curator of African American Collections in the Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library and assistant professor of African American studies—arrived later in life to a career as a historian and scholar. Earlier incarnations were as a respected defensive player for the NFL’s Kansas City Chiefs and Atlanta Falcons, an inventor (who sold Procter & Gamble a patent for a dental product), an artist, and the owner of an aging Chevy Suburban (more on that later).

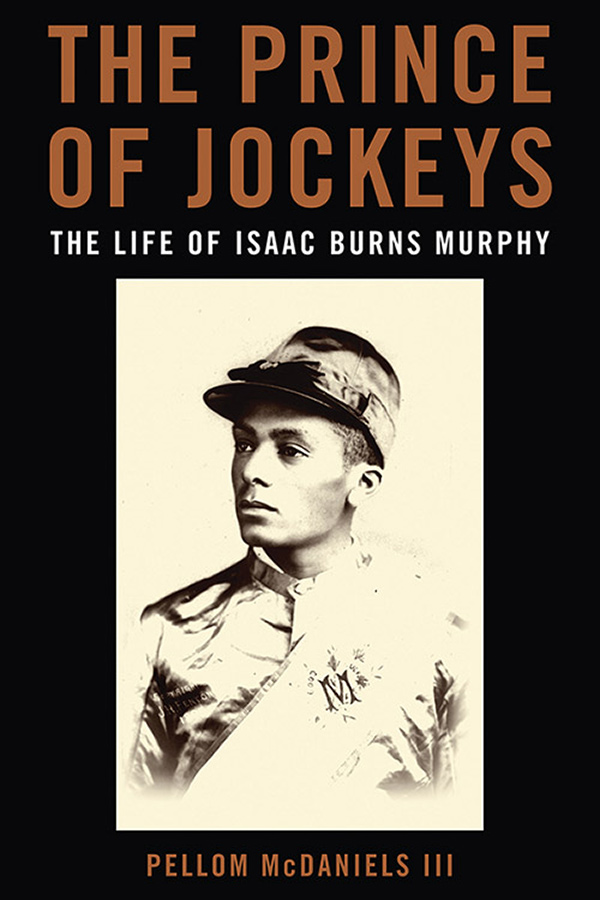

Of former NFL players turned academics, there have been relatively few on record. That only makes McDaniels work harder to paint a true picture of what sports have meant to African Americans, a view that dissolves many stereotypes. As McDaniels says in his new biography, The Prince of Jockeys: The Life of Isaac Burns Murphy, “To most Americans, athleticism is an inherent feature of blackness, directly linked to the mythology of race promoted by the founding fathers.”

His countervailing view, eloquently interwoven in the book, is that sports has exerted a powerful role in allowing African Americans to express their intelligence and drive, to learn collaboration and organizational skills, and to develop that chief ingredient of character: self-discipline.

Born Isaac Burns in 1861, Murphy spent his life in Kentucky, born to enslaved parents; his father served as a Union soldier, and his mother was one of very few women who owned land in postbellum Lexington. The young Murphy joined the world of horse racing at the age of fourteen and by the 1880s was making tens of thousands of dollars per racing season. Murphy won the Kentucky Derby three times, the American Derby four of the first five runnings, and had an unmatched winning percentage of forty-four. He was among the inaugural class of jockeys elected to the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in 1955. His life sounds like a tale of liberation, progress, and prosperity.

Yet it just as often wasn’t. This unmatched leader in the sport had more than his fair share of challenges. As Murphy’s career advanced, the primacy of black jockeys eroded as a result of the increased degree of gambling, the infusion of Irish riders, and fears of African American success and prosperity. Dirty tricks became the norm, with white jockeys colluding with gamblers to box in their black counterparts during races to prevent them from winning. Frequently, these same jockeys placed bets on the races because there was so much money to be made—legitimately and otherwise—in the industry.

The arc of Murphy’s career follows that of the country. Murphy lived, says McDaniels, through “the ‘second American Revolution,’ which gave people of African descent recognition as citizens; he died at the end of the same century, when those hard-fought gains were shattered by the adoption of government-sanctioned Jim Crow policies of exclusion and the unconscionable violence of lynching.”

Murphy died of pneumonia in 1896; with the passage of time, his grave in African Cemetery No. 2 in Lexington was forgotten. After a journalist found the gravesite, the vice president of the Kentucky Club Tobacco Company saw an opportunity to publicize his company while ostensibly honoring Murphy. The idea was to reinter him next to the famed racehorse Man O’ War at the entrance to the Kentucky Horse Park. That act separated Murphy from his beloved wife and, laments McDaniels, “from the generations of African Americans buried in the sacred space.”

In The Prince of Jockeys, McDaniels supersedes biography’s border, putting down novelistic touches—as, for instance, in his section on the solar eclipse of 1869, which ends: “For African Americans, whose lives had been changed by the Civil War, the rights and privileges attained through federal legislation, and the burgeoning possibilities for social, economic, and political growth, their eyes were fixed on a future in which they emerged from the darkness of slavery into the light of full citizenship.”

Beyond McDaniels’s obvious gifts as a writer and historian, there is what he brings to the book by virtue of being a fellow athlete. When he recalls his professional football career, McDaniels acknowledges feeling as if he were “on a treadmill, always an injury away, with younger guys behind me.” The question McDaniels has asked repeatedly in his examination of sports and African Americans is, “How is it that an industry that depends upon you is able to manipulate you?”

The answer—the only real one, for Murphy and McDaniels—is to build a reputation for hard work and honesty. Yet, even with that, McDaniels hedged his bets, holding onto that aging Suburban like a security blanket, in case—he says—it ever became necessary to pack up all his belongings and “move on to the next thing.” That “next thing” has proven to be illuminating the historical record, for which all of us can be grateful.