'Chaperone' Proteins Curb Bad Behavior in the Brain

Su Yang, Shanshan Huang, Marta A. Gaertig, Xiao-Jiang Li, Shihua Li

Most of us think of a chaperone as an adult who keeps teenagers out of trouble at a dance or overnight trip. But the word also describes a type of protein that can guard the brain against its own troublemakers: misfolded proteins that are involved in several neurodegenerative diseases.

Researchers at the School of Medicine have demonstrated that as animals age, their brains are more vulnerable to misfolded proteins, partly because of a decline in chaperone activity. The scientists were studying a model of spinocerebellar ataxia, but the findings have implications for understanding other diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s.

They also identified targets for potential therapies: bolstering levels of either a particular chaperone or a growth factor in brain cells can protect against the toxic effects of misfolded proteins. The results were published in January in the journal Neuron.

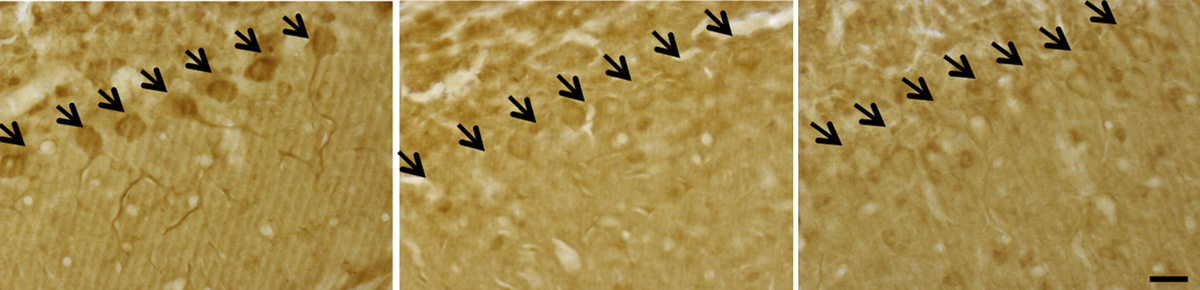

Scientists led by Shi-Hua Li and Xiao-Jiang Li, both professors of human genetics, devised a system in which production of a misfolding-prone protein that causes a form of spinocerebellar ataxia can be triggered artificially in mice at various ages. The misfolded proteins are toxic and interfere with the normal forms of the same protein.

Chaperones are proteins whose job is to prevent improper liaisons between other proteins; they prevent the sticky regions of proteins from grabbing something they’re not supposed to. Li’s team identified a chaperone called Hsc70 whose activity declines with age in the brain, while others’ activity does not.

To confirm Hsc70’s importance, the researchers showed that boosting cells’ levels of Hsc70 can bolster their ability to cope with misfolded proteins. Potentially, small molecules that increase Hsc70 levels could be used for treating spinocerebellar ataxia, says Xiao-Jiang Li.