Forward Thinker

What it takes to study Ebola in depth

Photo by Jack Kearse.

Since Ebola virus first emerged from the rainforest and was identified in 1976, it has surfaced—in relatively brief and isolated spates—in several West African countries.

But international concern about Ebola virus has blossomed along with the current outbreak, in part because of the havoc Ebola wreaks on the human body and the lack of previous knowledge about the disease.

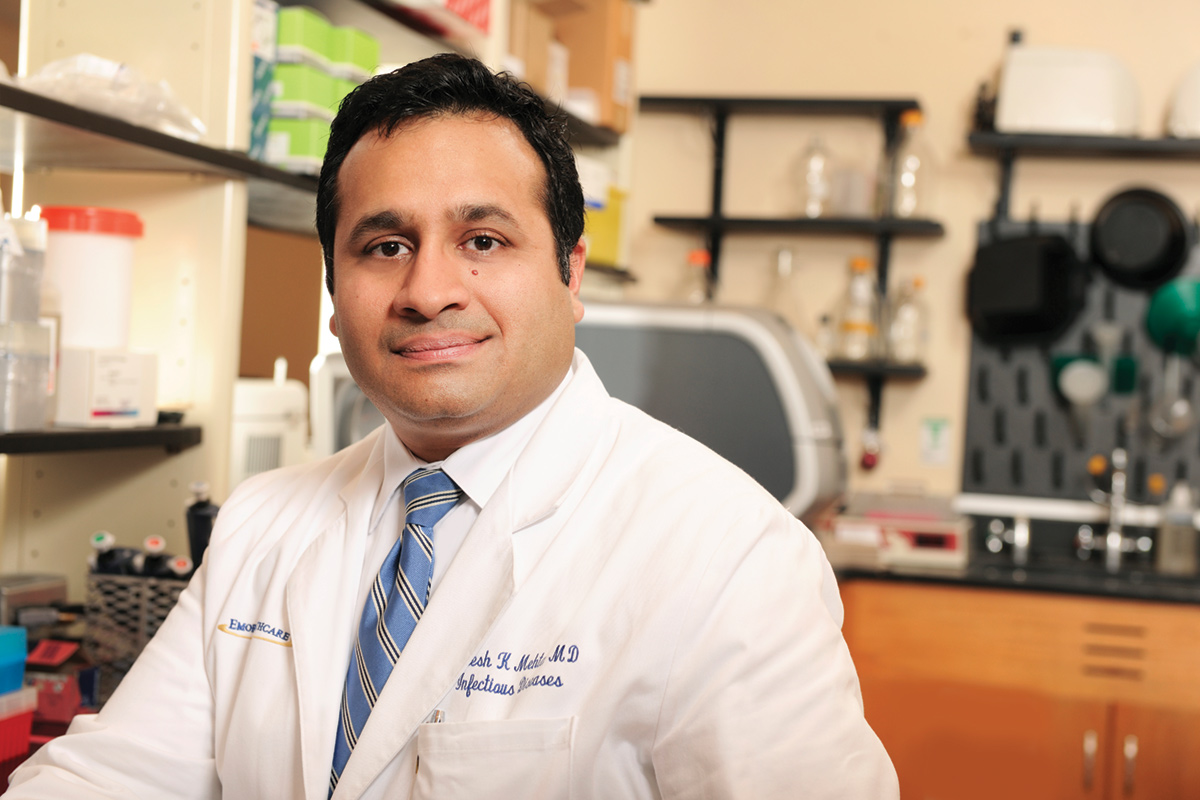

“It is one of those viruses that can be very devastating because it attacks the immune system directly. The virus infects immune cells and blocks the ability of the immune system to respond,” says Aneesh Mehta 99C 06MR 09FM, assistant professor of infectious diseases at Emory’s School of Medicine. “Once the dendritic cells and monocytes are infected, it gets into the lymphatic system, which allows it to spread rapidly and to have a devastating effect. It is using the immune system and killing the immune system at the same time.”

Mehta, who was the first Emory physician to care for Ebola survivor and fellow physician Kent Brantly, says treating Ebola patients in American facilities offers the opportunity to look in depth at the science, pathogenesis, and transmission of Ebola virus in order to develop better approaches to treatment.

“The ability to do that in the countries where outbreaks usually happen is low, because there is not a good health care infrastructure for treatment and even less

of a research infrastructure to look at the disease process,” he says. “In all of the US hospitals that have treated patients, with the help of the CDC and other federal agencies, we are able to put together the data being collected and study these patients to improve treatment in a way that has never been done before. We hope that knowledge will lead to better approaches for patients in the future.”

Although the level of care delivered to patients in the US can’t currently be transferred to those in West Africa, Mehta says there are key measures that can be taken in less-developed health care environments.

“Good electrolyte replacement and the ability to have lab testing close by could potentially have huge impact on controlling this outbreak. Whatever we can bring

to Africa may lower the fatality rate of the disease and result in more survivors leaving treatment centers,” he says. “That will hopefully encourage more patients to come into treatment centers earlier in the disease process. All of those things are needed to contain an outbreak like this—not just equipment and people, but the confidence of the communities where this is occurring.”

Strengthening health care infrastructures and keeping cultural differences in mind are important aspects of improving overall health in developing areas, especially

as the world becomes more interconnected by international travel, Mehta adds.

“It is a lesson for all of us in the international community that, whenever there are places where people can’t access good health care and basic measures they

need to improve health, it can lead to ripple effects that can influence us all,” Mehta says. “There is nothing like an infectious disease to show that.”