Ebola: From Microscope to Spotlight

Special Report

Photo by Jack Kearse

Twenty-nine days after the July morning he awoke in Monrovia, Liberia, feeling feverish, Kent Brantly stepped out of the isolation unit at Emory University Hospital, a survivor of infection by the deadly Ebola virus.

His wife, Amber Brantly, had not been able to touch her physician husband since July 20. That was the day she and the couple’s two young children kissed him good-bye, then boarded a plane for Texas to attend a wedding.

The moment he emerged from his hospital room free of Ebola, she walked to his side and, taking his left hand, she slipped his wedding ring back onto his finger.

The extraordinary efforts that led to this moment brought together public and private entities from around the world in a race not only to save American lives, but also to learn more about a virus that has decimated thousands in West Africa.

International media coverage of the treatment of patients at Emory University Hospital (EUH), two patients sent to the Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, and two cases at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas has focused attention on the Ebola crisis and spurred increased response from the American government and governments around the world. This support is critical, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), which warns that the disease could become endemic, infecting more than one million people by January, if efforts to thwart its spread are not “drastically escalated.”

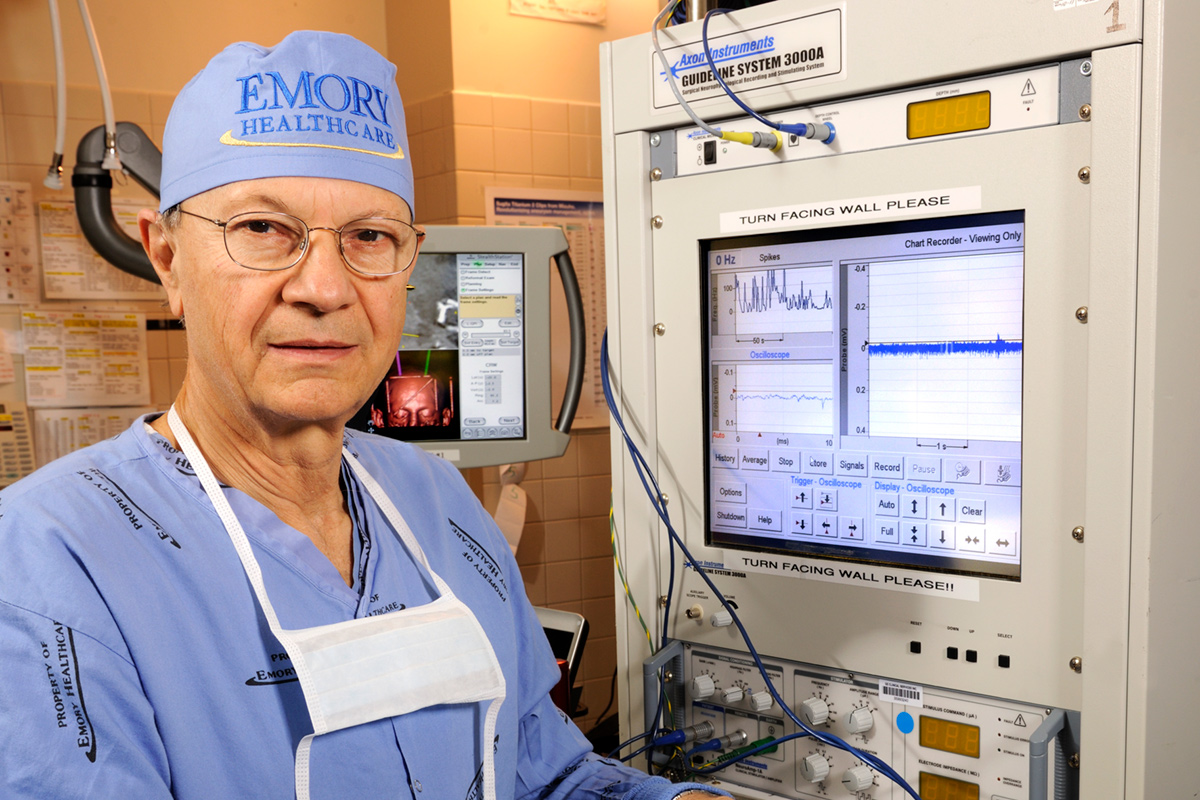

At Emory, infectious diseases specialist Bruce Ribner had been preparing for twelve years to treat a case like Brantly’s.

In 2002, officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) approached Emory with the request that the two organizations work together to develop a special isolation unit at EUH. They wanted a secure place to bring CDC employees—from the headquarters or from the field—who had been exposed to or infected with any number of dangerous pathogens.

“We agreed, and over the course of several months came up with a model for developing a unit that could care for individuals with any communicable disease with any mode of transmission,” says Ribner, director of Emory’s Serious Communicable Disease (SCD) Unit, who served as Emory’s principal investigator in developing the isolation unit.

Since it was established, the health care team charged with staffing the unit have done their jobs “quietly, effectively, and efficiently,” regularly training for every eventuality, including Ebola, Ribner says.

Then, on Monday, July 28, Ribner received the call from the US Department of State asking for permission to come visit the unit. A team arrived on Tuesday, and on Wednesday morning Ribner received a call from the agency asking to bring Brantly from Liberia to Emory for treatment.

The Ebola outbreak had been raging in Africa since March, but it was not until Brantly and fellow missionary worker Nancy Writebol were infected that the story caught fire in the news media, sparking a tumult of speculation about the Americans’ fates.

“I discussed it with a group of administrators— Bob Bachman, chief executive officer for EUH; Bryce Gartland, vice president of operations; Ira Horowitz, chief medical officer; and Nancye Feistritzer, vice president for patient care services and chief nursing officer—and immediately they said yes,” Ribner says.

'We were finally going to use our training'

The next two days were a frenzy of focused activity—preparing the SCD unit, recruiting trained health care volunteers to staff it, and preparing for the media onslaught that was sure to come to Emory along with the first American with Ebola ever to be treated in the United States.

“Somewhere between the excitement and anticipation among the team—we were finally going to use our training, we were going to be the first people in the developed world to manage patients with Ebola—we began to get pushback from some employees. There was a lot of anxiety,” Ribner says.

To address those concerns, Bachman coordinated systemwide town hall meetings for each shift to educate staff about Ebola and to answer questions about the disease and how Emory would care for these patients while protecting the safety of the staff and the other patients in the hospital.

“We knew when we agreed to take these patients here that only 5 percent of the problem would be taking really good care of the patients. The other 95 percent would be to manage the message and the media and the overall public reaction,” Bachman said at one of the town hall meetings held in the early days of Brantly and Writebol’s treatment (see sidebar on Emory’s media and communications response). “We realized we needed to have these conversations about this disease, which really does strike fear in the minds of many people.”

Crystal Johnson 00N has been on the staff of the SCD unit for eight of her fifteen years at Emory. She convinced her colleague Laura Mitchell 95OX 97N to join the unit as well. Despite her own enthusiasm for the assignment—she’d wanted a chance to work with high-level infectious diseases since seeing the 1995 film Outbreak—Johnson admits being nervous when the unit was activated.

“Our previous protocol did not have us wearing the full protective suit,” Johnson says. “Then they called us in the day before the patients arrived and told us they were changing our PPE [personal protective equipment]. From that day I felt that, yes, we were going to care for the patients, but the number one priority was our safety, the safety of everyone else in the community, the rest of the hospital, and out in the world. I felt confident going in.”

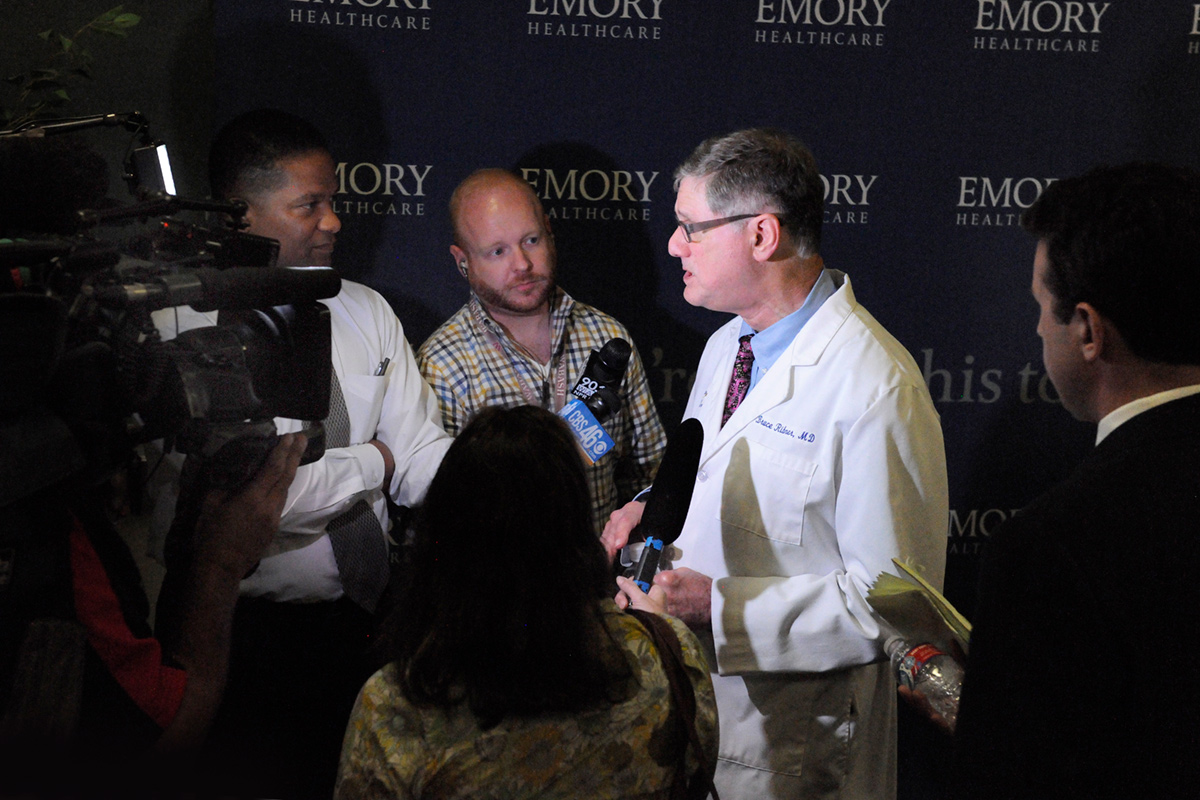

Bruce Ribner, director of the SCD unit, addresses reporters' questions at a press conference.

Photo by Jack Kearse.

All the members of Emory’s SCD unit are highly skilled and trained volunteers, like Johnson, who work in many different units at EUH and Emory University Hospital Midtown (EUHM). In all, more than 125 Emory staff members—from doctors and nurses to lab technicians and maintenance personnel—helped care for Emory’s Ebola patients.

Jason Slabach 13N was not part of the SCD unit before it was determined that two Ebola patients would be treated at Emory at the same time. Before earning his nursing degree at Emory, he practiced as a paramedic for three years in Virginia; for the past year he has worked in EUH’s cardiothoracic and vascular ICU caring for patients recovering from heart surgeries, including transplants.

“They were trying to prepare for the long haul of taking care of two patients over the next couple of months, and they knew that they would need additional supplemental staff. I was asked if I would be interested in joining and getting trained,” Slabach says. “They wanted ICU nurses because these patients can be very sick. I also have worked with different levels of PPE with fire and EMS in my career as a paramedic through hazardous materials training.”

He agreed, after speaking with his wife, Katie Allen Slabach 10OX 12N, a nurse in a medical cardiac unit at Emory.

“She had some apprehension early on, as did I,” he says. “But receiving the training made me feel completely comfortable that the things we were doing would be 100 percent correct.”

Slabach remembers encountering the subject of Ebola as a high school student in Virginia when he read The Hot Zone by Richard Preston. The 1994 best seller examined the origins of the Ebola viruses and gave vivid descriptions of early outbreaks in Africa and one in a primate facility in Reston, Virginia, that had government agencies frantically working to identify and contain the deadly virus.

The gruesome depictions of Ebola’s symptoms in the book and in movies like Outbreak, as well as the widely publicized 40 to 90 percent mortality rate of the disease, were fuel for the explosion of negative public reaction that accompanied the first announcement that Brantly was being brought back to the US for treatment. Opponents lashed out in fear, and Ribner bore much of the impact.

“My email was a tsunami of hate mail,” he says. “I got hundreds of emails. Nothing I got was threatening, but people were saying I should die and burn in hell for bringing the plague to the United States.”

He likened the reaction to the public panic surrounding HIV in the early days of AIDS.

“You saw hospitals refusing to take patients with HIV. Doctors and nurses refusing to take care of patients. Is it that much different with Ebola? Both reactions were born of an ignorant fear of the unknown. At the time, HIV was a new virus. No one knew where it came from or how it was transmitted. It was purely fear of the unknown,” Ribner says. “The only difference between then and now is the knowledge and the comfort level we have acquired that HIV is not an easily transmissible disease.”

Unlike HIV, Ebola is not an unknown virus. The CDC has been dealing with Ebola since the first case was discovered in Africa in 1976. There have been a number of outbreaks in Africa, but a combination of factors—including native mistrust of outside health care workers, local care and burial customs, and more urban settings—have made the current outbreak the largest in history.

“We are talking to the movers and shakers in Washington about how federal agencies can target interventions in the most effective way possible, and it all starts with the availability of gloves, gowns, and hoods to protect health care workers,” Ribner says. “Health care workers are at the greatest risk of infection, not because of stupidity or carelessness, but lack of equipment.”

Emory-trained SCD nurses (from left) Crystal Johnson, Laura Mitchell, and Jason Slabach.

Photo by Kay Hinton

The treatment of patients just down the street from the CDC has offered an unprecedented opportunity to study the disease.

“Ebola is only a young disease in terms of epidemiology and what we have learned about it. After learning the patterns of this disease and the virus and increasing what we know about it, we can figure out new strategies for treatment,” Ribner says.

Now that Brantly and Writebol have recovered, they have agreed to work with the CDC on Ebola research. Their blood is being monitored for abnormalities during follow-up care, and the CDC is undertaking a research project on their bodies’ immunity to the disease.

“Even though the CDC has been dealing with Ebola for forty years, the laboratory facilities are so limited in Africa that this level of research has never before been possible. They were trying to collect blood samples on filter paper in Africa to do studies,” Ribner says. “This is the first opportunity that most of our colleagues at the CDC have had to do the intensive testing they have wanted to do, and the patients both have expressed an interest in helping us understand this infection.”

Ultimately, the goal is to provide effective treatment strategies to health care workers on the front lines of Ebola outbreaks in Africa.

“We continue to provide feedback and information to health care providers in Africa in the hopes that we can bring the mortality rates down,” Ribner says. “If we can give them advice on changing the fluids and the content of the mineral solutions they are providing to their patients and help them understand ways to improve survival in a developing environment, then everything we have done was worth doing, no matter the outcome.”

‘We could save lives’

The notion that the United states would not have seen Ebola cases if these patients hadn’t been brought here is “foolish,” Ribner says.

“To this point, the United States had just been a little lucky, with all of the outbreaks on the African continent, that it had not come here,” he says. “Anytime [someone] traveled to another country in Africa by airplane, they could just as well have come here.”

Because of the proximity of the CDC and its special pathogens lab, Emory was the logical choice for treating the first US Ebola patients, Ribner says.

“It was important to show that we could effectively take care of Ebola patients. It was a good idea to bring these patients to our unit, where we have this training and where the resources of the CDC were right down the street. If we could do this safely, and show that our personnel would be safe, we could save lives,” he says.

The care that EUH provided its patients and the safety protocols it followed are transferrable to other health care facilities. The isolation unit at the Nebraska Medical Center, built in 2005, was modeled after Emory’s unit. Ribner spent hours on the phone with Phil Smith, medical director of the Nebraska unit, sharing information after the decision was made to bring a third American Ebola patient, Richard Sacra, to the Nebraska unit for treatment. A fourth American, Ashoka Mukpo, arrived for treatment in Nebraska on October 6.

A man who arrived in Dallas, Texas, from Liberia on September 20 became the first diagnosed Ebola case in the US after becoming symptomatic several days after his arrival. Thomas Eric Duncan was admitted to an isolation unit at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital on September 28. He died on October 8.

The operation of Emory’s SCD unit—which was reactivated on September 9 when a third American Ebola patient was admitted to EUH for treatment—requires elaborate coordination among Emory Healthcare staff; university administration; federal, state and local government organizations; and foreign governments.

At the center of this complicated web are the critically ill patients whose lives hang in the balance. When they arrived in a specially equipped jet from Liberia, Brantly and Writebol were more ill than anyone expected.

“We did not anticipate how sick they would come to us, how metabolically abnormal they would be. If Dr. Brantly had been older, he would have been dead,” Ribner says. “His electrolytes were out of balance, and he was experiencing heart arrythmias because of those imbalances. Being a doctor, he discussed treating patients in Africa and how, frequently, patients would be writhing in bed sick, then suddenly sit up and clutch their chests and die. We suspect that many of those deaths were cardiac deaths caused by cardiac enzyme imbalances. I am sure that if Dr. Brantly had gone on in that level of care for another day, he would have suffered cardiac death.”

Before she headed in for the night shift on August 2, SCD nurse Crystal Johnson watched on the news as Brantly walked from the ambulance into the isolation unit.

“When he walked in, it gave me a different picture. I thought he would be a lot better, but when I took care of him that night I saw he was really sick. Every hour we were all on edge because he was decompensating quickly,” Johnson recalls. Many of the frightening symptoms of Ebola infection were present—hemorrhaging from the eyes, petechiae (small red or purple spots on the skin caused by broken blood vessels) all over his body, weakness, fever, copious diarrhea. “He really had to hold on to me to get up and down,” says Johnson.

To limit the number of health care staff exposed to the patients, nurses had to handle the patients’ every need—from drawing blood and taking vital signs to administering IV medications and cleaning up bodily fluids—all while following the stringent guidelines the team had set for itself.

Before the first patient arrived at Emory, the team drilled together on all safety protocols and dedicated themselves to keeping each other safe while providing the best possible care for the patients. Despite her years of training with the unit, Johnson says every member of the team trained as if it were his or her first day.

“It was very intensive, like the military. They would get in your face; they were testing you to see if you would crack under pressure,” Johnson says. “They had to make sure that, if things happened in the room, you wouldn’t panic and put everyone else in the family at risk. We take that for granted. When we work on our regular units, what another nurse does isn’t important to you. You think, ‘That isn’t me, I am going to do what I have to do.’ But here you have to worry what the person does before you, what the person does after you, and what you are going to do, because one mistake can kill us all.”

“And that is how we became a family, that Friday afternoon,” Mitchell adds.

Family is how the team came to think of itself, agrees Sharon Vanairsdale, clinical nurse specialist for the SCD unit.

“We had to be a family, we relied on each other to be safe. It was so nice to see the physicians, the nurses, the staff, all working together on that level. There were no egos—there couldn’t be,” Vanairsdale says. “Everything that went into and out of the unit was controlled by the family. We all had a lot on our minds, more than just what was happening in the isolation unit, so we had to take care of each other.”

Carolyn Hill, nursing unit director for the SCD, and Vanairsdale monitored the nursing staff in both isolation rooms at all times from the anteroom at the unit’s center, making sure all procedures were followed and supporting the nursing staff with any needs that came up.

“We all really worked and functioned as a team. It was truly collaborative, not just among the nurses, but the staff, the physicians, the lab. If something changed, we would walk through the process as a true team decision,” Hill says.

Following the strict procedures required for patient care provided a level of comfort for the team in a highly stressful care environment.

“We spent a lot of time being instructed in the PPE, a lot of practicing putting it on and taking it off—donning and doffing, we call it. We memorized the steps, but we also practiced this with people observing us who are experts, people who have written books and traveled the world talking about containing viral hemorraghic fevers” Slabach says. “They explained where there were possible weak points, possible areas of making mistakes so we understood those.”

Every moment of the team’s time in the unit was carefully scheduled by “logistics officers” Hill and Vanairsdale.

“We wanted the nurses to be concerned only with patient care,” Vanairsdale says. “We scheduled everything to eliminate any distraction from the patients—when the physicians came in, when to perform the labs, when they would take breaks, when the families visited—it was all very well coordinated so the nurses at the bedside could take care of the patients and protect themselves.”

As physically devastating as the disease was for Brantly and Writebol, the emotional strain for both—and for the care team—was equally great. Writebol told one of the doctors caring for her that she thought she had been brought home to die.

The patients, who watched the media storm about them on television and via tablet computers, struggled with what they heard.

“They were able to get messages through Facebook and the different social media networks. It was hurtful to read the articles and hear the things people were saying,” Johnson says. “Dr. Brantly would explain to me that he didn’t go over to take care of Ebola. He went over there to take care of day-to-day people in Africa and an outbreak happened. He explained that his unit was the only one still standing, all of the other isolation units had shut down. His unit was the only one ready to receive patients.”

Despite the negativity, both patients knew they had the support of their families and countless others around the world.

“I prayed with both of them at the bedside, and I made sure they knew that millions of people were praying for them who didn’t even know them,” Slabach says.

Both patients were interested in learning about the people caring for them, always concerned with how they were feeling and inquiring about their lives and families outside the unit. In turn, Slabach and his colleagues supported Brantly and Writebol emotionally as well as physically.

“Toward the end of their time at Emory, they were feeling great, and we had the opportunity to try to make their lives easier and more fun, to help them deal with the emotional side of kind of being in a prison, being cut off from the outside world,” he says. “We were their link to the outside world. They could talk to their families through glass, but we were the ones going out and coming back in every day.”

Johnson says the nurses had a “spa day” for Writebol, bringing in lipstick and treating her to a pedicure; another nurse brought in a Nerf basketball set for Brantly’s room.

“Kent beat me first game, but I told him that you really can’t win playing a guy with Ebola, it is a lose-lose situation,” Slabach laughs. “I told him I gave him a handicap, but he told me I had no excuse losing to a guy with Ebola.”

Writebol and Brantly could see one another through windows on the doors to their rooms and often spoke to each other by phone during their recovery, praying together and even making a competition of who was recovering faster once the imminent danger had passed.

On the day Writebol was discharged, Brantly stood at the door of his room with Johnson, watching his friend as she joyfully walked out of her room. The pair blew kisses to one another through the glass and Writebol called out to him, “See you in a couple of days.”

Two days later, Brantly finally got the news that his blood had tested negative for the Ebola virus on two consecutive days.

“We had him take a shower and put on a set of scrubs, he came out of the room over the red line—the red line was a no-no for him before—and he walked into the anteroom and then into the hallway. His wife walked up to him and put his wedding band back on his finger. That was the ‘wow’ moment,” Johnson says. “He hugged us all without any of the Tyvek suits on, then he turned and grabbed his wife’s hand and they walked down the hall like they were getting married again. That was just beautiful.”