Dual Identity

On Being Muslim and American

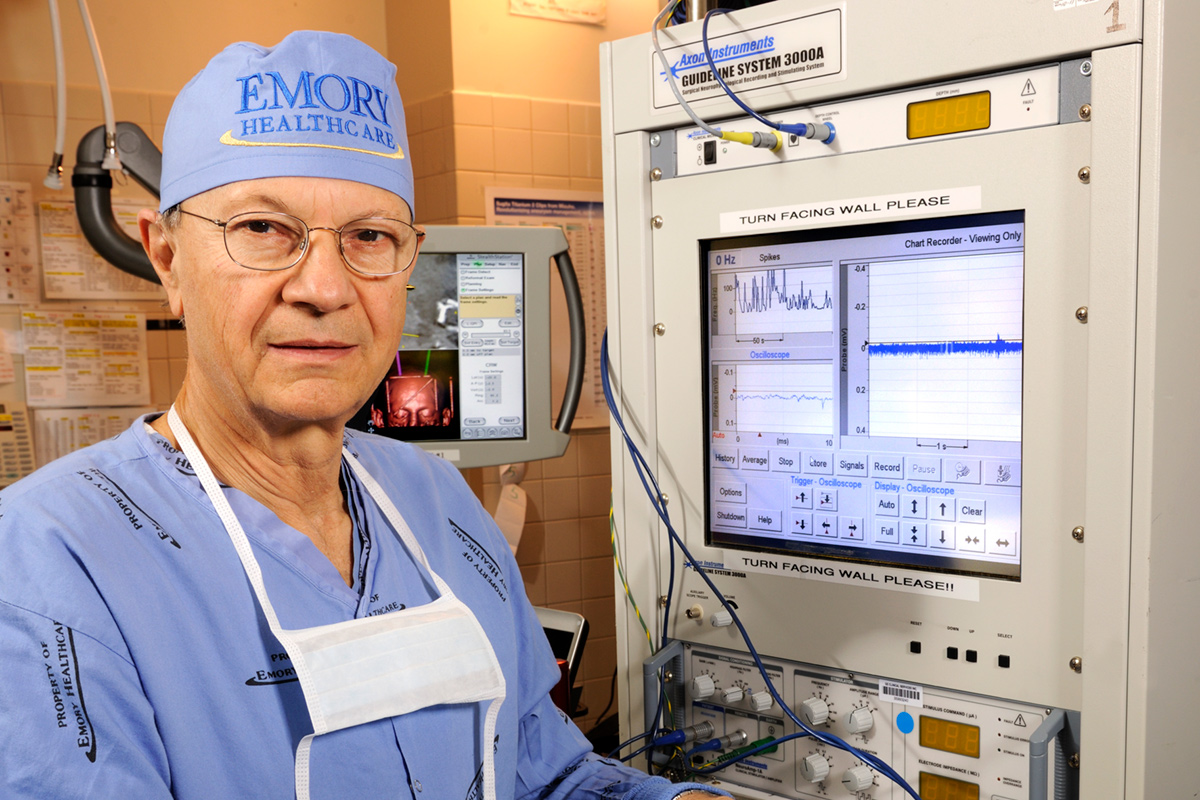

Photo by Kay Hinton.

It's probably not a book that a young man could write—and that is to its credit. The volume is boldly titled What Is an American Muslim? Embracing Faith and Citizenship, and the "old soul" behind it is Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na'im, Charles Howard Candler Professor of Law, associate professor in Emory College, and senior fellow of the Center for the Study of Law and Religion.

As the main title's question implies, this is a book genuinely puzzling out American Muslim identity, in the process of which An-Na'im places his own identity cards on the table: he writes as a husband, father, and grandfather concerned for the future.

Nonetheless, it's a work of unfailing optimism. The market for studies of Islamophobia has remained strong since 9/11, but An-Na'im refused to write such a book. There is no good reason, he says, why Muslims should "stand back to be either attacked or defended."

What is an American Muslim? By Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na'im, Oxford University Press

Born in Sudan, a former resident of England, and an extensive traveler, An-Na'im has logged the miles to be able to say, "Comparatively, American Muslims are much better off than Muslims in many places, including Western Europe." His eyes are open—he knows that there have been violent acts against Muslims here. But in twenty years of living in the US, An-Na'im never has had such an experience.

The key response, in his mind, is for Muslims to assert agency rather than retreat into victimization. "Socially, culturally, politically, there always will be good and bad," he says. "The question is where do you stand? I am responsible for the square I am standing in, regardless of what goes on in the world."

America's checkered past with regard to religious oppression, ironically, can be a positive for Muslims. "There is a history to this," An-Na'im says. "Muslims are not the first to face hostility. America is a country formed by pilgrims escaping persecution and by the richly layered histories of religious communities that have experienced persecution and fought back," including Catholics, Jews, and Mormons. That resistance resulted in a cultural pluralism, of which our constitutional provisions are an important expression.

An-Na'im hails from a part of the world where identity questions always have been paramount. After Sudan achieved independence from Britain in 1956, the questions proliferated: was it African, Arab, Middle Eastern, Muslim? According to An-Na'im, "Reality defies uniform, monolithic identities. Nonetheless, ambitious politicians keep pushing for that because it is a way to keep people off balance."

Sudan's postcolonial fight for a national identity was destroying families and whole regions of the country. An-Na'im, then twenty-two, joined forces with Mahmoud Mohammed Taha, the so-called Gandhi of Africa[emdash]a relationship chronicled in a 2006 New Yorker piece.

Taha wanted to establish the Republic of Sudan and to do so with complete transparency. In 1985, he became an enemy of the state for distributing a pamphlet protesting the imposition of Sharia by then-president Jaafar al-Nimeiri. Having involved women in his movement, Taha couldn't abide an interpretation of Sharia that viewed them as inferior. True Sharia law, he believed, had the ability "to evolve, assimilate the capabilities of individuals and society, and guide such life up the ladder of continuous development."

He was arrested and charged with heresy and sedition. A day before Taha would be executed, most of his four hundred supporters were taken into custody, a fate that An-Na'im narrowly escaped. His sister, though, was detained; when he went to advocate for her, the young lawyer found himself part of the negotiations for everyone's release, which was eventually granted.

For a young man raised in a conservative Muslim home, these events were life changing. "I am so fortunate to have seen someone in flesh and blood who said, `I uphold my human dignity on my own terms,' " he recalls.

An-Na'im's book, in its way, is as passionate as anything that Taha wrote. It is directed primarily at Muslims: an unabashed appeal for them to embrace American citizenship fully—acknowledging all its rights and responsibilities—and to define their faith for themselves.