People of Letters

The decades-long “The Letters of Samuel Beckett” project has created a legacy of former students spread across disciplines — and the world — who earned invaluable scholarly research experience at Emory.

It was September 2012, and Lauren Upadhyay was an Emory grad student in France researching her dissertation on the 20th-century French novelist Marguerite Duras when she got the email from Laney Graduate School. It was a call for part-time student researchers to work on “The Letters of Samuel Beckett.”

Lauren Upadhyay 15G, teacher and researcher

But she decided to apply for the job anyway.

“Beckett is adjacent to my research, but I hadn’t spent much time reading him,” says Upadhyay. “What I knew, I liked. And I thought the project would be a really cool thing to do.”

The next three years working on the project would be more than “cool” for Upadhyay. She would search for letters, photos and newspaper clippings in archives and libraries in France and the U.S. She would track down people and places mentioned in those documents all over Europe. She would sharpen her investigative and reporting skills, aid her own research, bolster and burnish her CV, and make connections with some of the world’s foremost literary scholars.

She would also obtain the prestige and satisfaction of having been one of more than 175 Emory grad students and 200 undergrads who contributed to the project, which is now complete after 33 years.

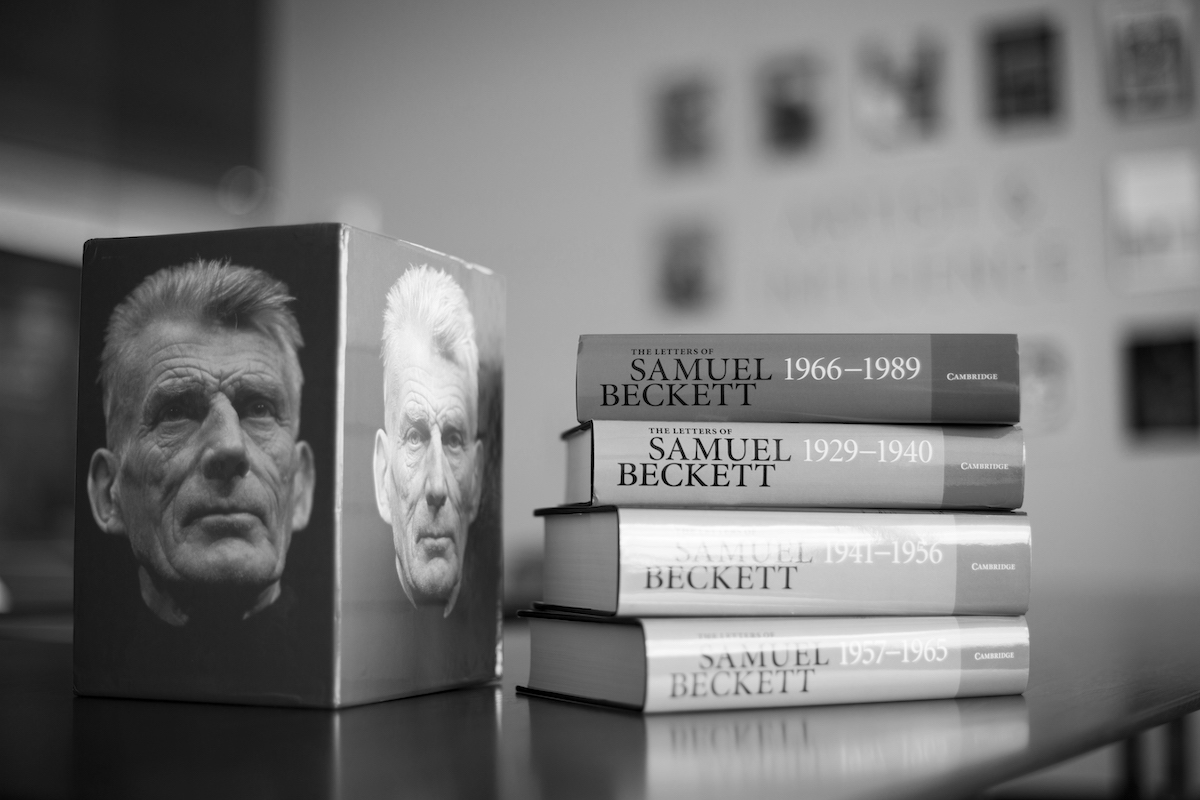

“Every student has their own story,” says Lois Overbeck, noted Beckett scholar and co-editor of all four volumes, published by Cambridge University Press. “These students have been the arms and legs of the project, running to the library to check this and that. And along the way, they’ve grown as scholars through the project.”

When Overbeck and founding editor and fellow Beckett scholar Martha Dow Fehsenfeld first brought the nascent project to Emory in 1990, news quickly spread through the academic, theater and literary communities and boosted the university’s reputation all over the world.

“It was a deciding factor that brought me to Emory,” says Patrick Bixby 03G, current president of the Samuel Beckett Society who arrived as an aspiring scholar in 1998 and worked on the project for five years. “It was a hub for Beckett scholars and theater people and other folks in the Beckett orbit. It was super helpful for me as a younger scholar to meet and learn from people on a project that aligned so closely with my interest, not to mention being mentored by the likes of Martha Fehsenfeld and Lois Overbeck.”

Patrick Bixby 03G, current president of the Samuel Beckett Society

“This was a side of a writer who was known to be reticent and reclusive,” says Bixby. “It opened a window into his life and his career — not only who he was as an individual, but also him working out an aesthetic theory, finding his way as he got into the theater world. There’s correspondence with directors and actors, all a means of getting a sense of his vision of his works.”

There was also a practical advantage to participating in the project, even for well-versed academics. “It was a marvelous experience, not just to learn and practice key research skills for primary research, but also to be welcomed into a larger research community,” says Derval Tubridy 96G, who worked on the project from 1993 to 1996, both from Emory and from Trinity College Dublin, where she earned a PhD in literature. Her experience with the project, she feels, was key to her being awarded a Fulbright Fellowship in 1998.

Derval Tubridy 96G, professor at Goldsmiths and co-convener of the London Beckett Seminar

And the searches weren’t confined by the library walls. Sometimes students would be tasked with tracking down rights holders and people who had received letters to get permission for reprinting. Other times, they’d have to make phone calls to, say, Germany or Greece to verify a business or location that Beckett had referenced to make sure it was cited correctly and that it had actually existed. And occasionally they’d talk to actual contemporaries and correspondents to further flesh out the context of a letter.

Obviously, these skills had appeal beyond would-be Beckett scholars. And it’s a good thing: Given the breadth of material — more than 16,000 letters in several different languages spanning 60 years, including some of the most turbulent decades in European history — it was going to take a larger and more diverse crew of literary enthusiasts.

“We enlisted students from more than one discipline and more than one language,” says Overbeck. “It was always a team effort among the students. It was a good opportunity to learn from each other.”

Upadhyay credits her involvement with the project for honing her research skills and teaching her how to build relationships within the research community, among librarians and archivists who undoubtedly helped her finish her dissertation and obtain her PhD in French language and literature. She also suspects that, when applying for a prestigious Chateaubriand Fellowship in 2014, she got not one but two French intellectuals to sponsor her because of the Beckett rub.

“I have no proof of this,” she says. “But I’m almost certain that having that work in my files and on my resume was one of the reasons they chose to work with me.”

Getting to know Beckett also had an impact on Upadhyay’s personal life, just as it most likely did for many of the graduate students who got to better know the man and his work. To this day, she has a line from Beckett’s most famous play, “Waiting for Godot,” in charcoal on the wall of her apartment in New York. It reads: Was I sleeping, while the others suffered? Am I sleeping now? Tomorrow, when I wake, or think I do, what shall I say of today?