Hard Pressed

A closer look at the history of American free speech

Wikimedia

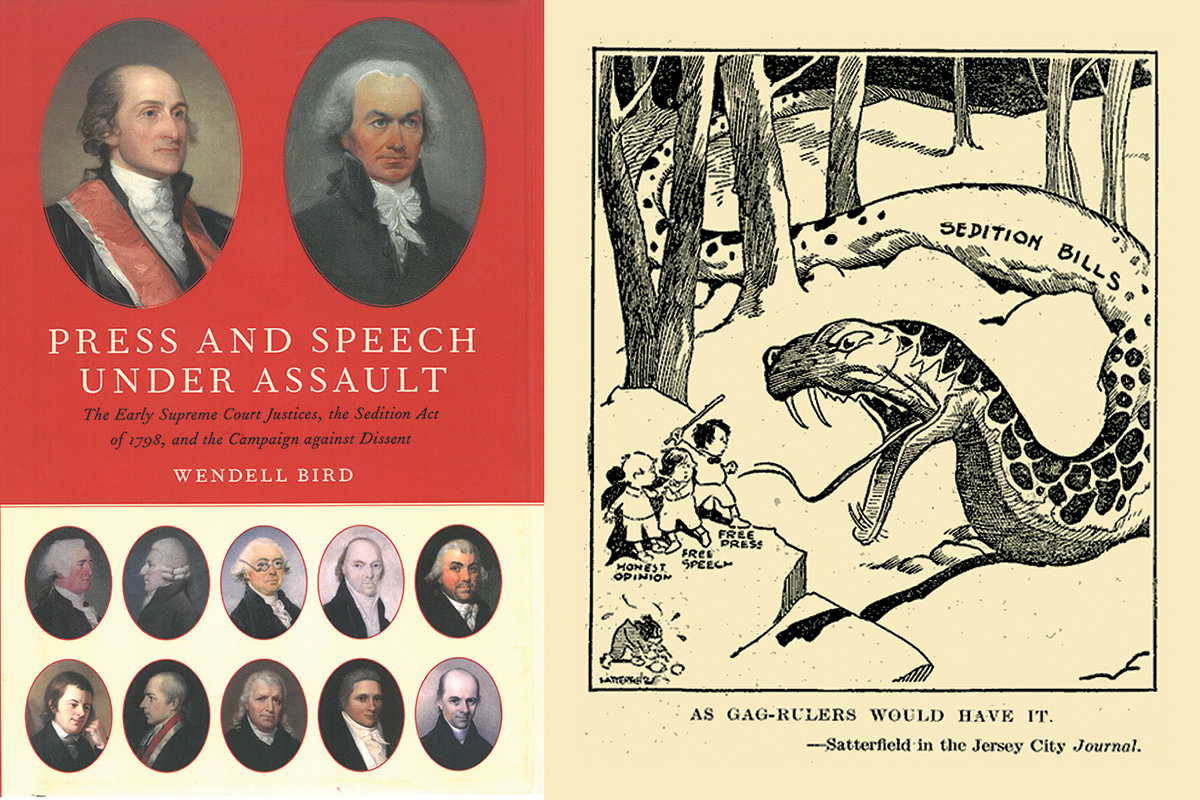

The Sedition Act of 1798 made it a crime, punishable by a $2,000 fine and two years in prison, “if any person shall write, print, utter, or publish . . . any false, scandalous, and malicious writing or writings against the Government of the United States, or either House of the Congress, . . . or the President.”

For Americans who take freedom of the press seriously, these might seem like dark days. President Donald Trump, speaking at the Conservative Political Action Conference in February, again described journalists as “the enemy of the people.” That same day, White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer banned major news outlets—including the New York Times, CNN, and the BBC—from his daily briefing. A day later, however, those same outlets regained access.

It’s worth looking at where we were to understand where we are. Wendell Bird, a visiting scholar at Emory School of Law, has done so in Press and Speech under Assault: The Early Supreme Court Justices, the Sedition Act of 1798, and the Campaign against Dissent(Oxford University Press). As the first published review of the book—by David Anderson in Texas Law Review—noted, “Bird’s book is transformative historical research,” which “requires a substantial rethinking of received wisdom about the framers’ views.” And, indeed, Bird takes aim at the “typical textbook history” of the First Amendment, the early Supreme Court, and the Federalists in the 1790s—a history that he proves false in important areas.

“Most Americans—including most American lawyers—are surprised to learn that [dissent] is a crime in most other countries . . . and that it was a crime in the United States until 1964 or later,” Bird says.

The story begins with Sir William Blackstone’s famed Commentaries on the Laws of England, a four-volume treatise on English common law published in the 1760s that arguably made a greater splash on this side of the pond.

Blackstone’s claim that “liberty of the press” and speech meant liberty only from a requirement of prior licensing or approval, and that this was enshrined in common law, is untrue, according to Bird. In fact, Blackstone provided one of the narrowest definitions of speech and press at the time, yet his words carried great weight.

The Sedition Act became law under President John Adams and generated a number of cases, serious and less so. Benjamin Franklin’s grandson, a newspaper editor, was arrested for criticism of Washington and Adams but died of yellow fever before trial. In a second case, when a cannon went off during a parade to welcome Adams in Newark, New Jersey, a tipsy man named Luther Baldwin yelled, “I hope it hit Adams in the arse.” A $100 fine hit him in the wallet.

Although enforcement ended once Jefferson took office, the battles the act stirred were profound.

“The Sedition Act controversy was the first major debate on the meaning of the First Amendment, and the early justices were the first federal judges to interpret freedoms of press and speech, and the only Supreme Court justices to do so for nearly a century,” says Bird. At issue were “what rights individuals retain and did not surrender to government, including the right to dissent from the administration and its measures.”