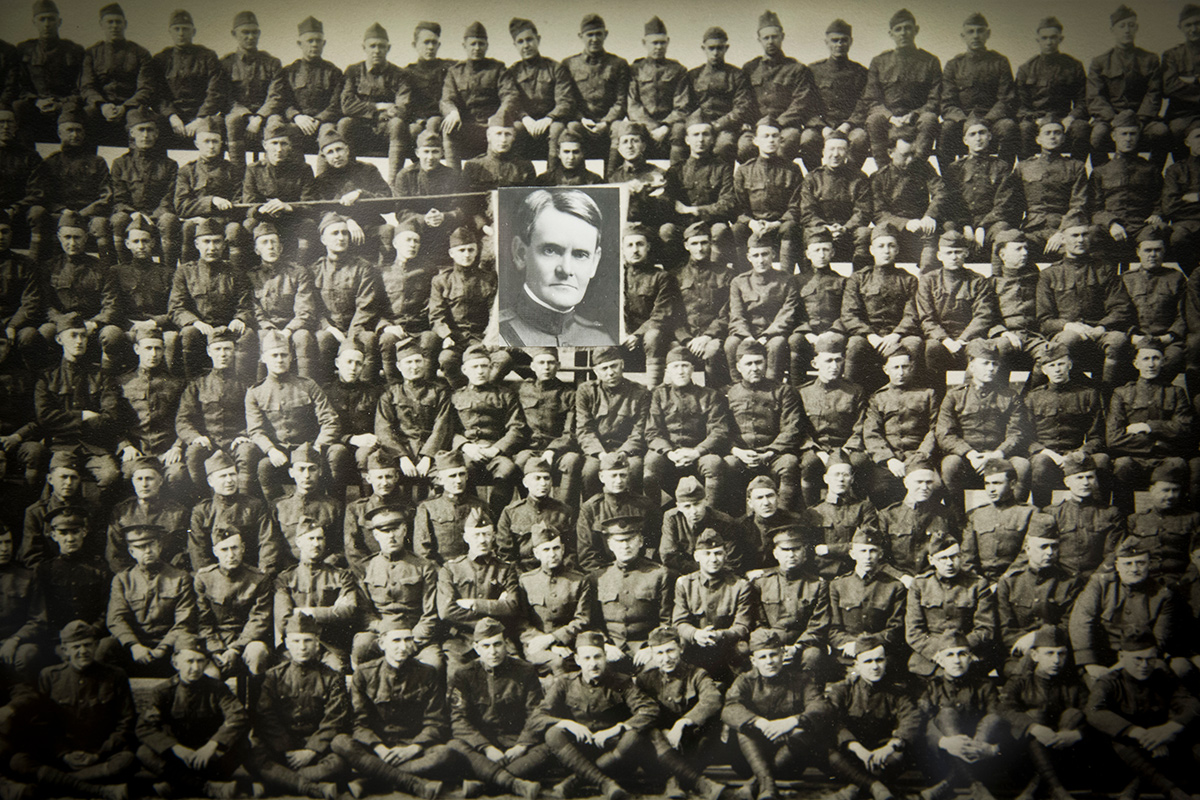

When Emory Doctors Went to War

A medical unit originally staffed and outfitted for 500 patients welcomed the war's end with more than 2,000

Courtesy of Render Davis

In April 1917, shortly after America’s entry in the Great War, a call went out from the US Army and the Red Cross to medical schools across the country. Doctors and nurses would be urgently needed to staff hospitals in support of the hundreds of thousands of newly enlisted “doughboys” who would soon head overseas to join British and French Allies fighting Germans in the trenches snaking across Europe.

When Emory medical school Dean William Elkin received the request, he turned immediately to Edward Campbell Davis to organize the school’s medical unit. Davis, a professor at the school and cofounder of Atlanta’s Davis-Fischer Sanatorium (later Crawford W. Long Memorial Hospital and now Emory University Hospital Midtown), had served as an army surgeon in the Spanish-American War and retained his military rank. Without hesitation, he began assembling a team of Atlanta’s and Georgia’s prominent physicians, skilled nurses, and other staff.

“Every doctor and every nurse that can be spared must be sent to France, and they must go at once,” wrote Cora Harris, a noted Atlanta journalist.

The initial call was to organize a five-hundred-bed hospital to be funded through popular subscription. Recognizing the scale of this endeavor, in August 1917 the federal government appropriated $40,000 to equip the Emory unit, soon to be officially designated Base Hospital 43. A local fundraising campaign by the Atlanta newspapers netted $7,000, which was used to purchase a fully outfitted ambulance.

Finally, in April 1918, unit officers received instructions to report to recently constructed Camp John B. Gordon (the present site of DeKalb Peachtree Airport) for basic training. They also learned that the unit’s hospital would be increased to one thousand beds.

That June, unit members boarded the SS Olympic (sister ship of the ill-fated Titanic) for the voyage to England, arriving in Blois, France, late that month. Emory Unit Base Hospital 43 of the Allied Expeditionary Force was now operational.

By mid-July, casualties began arriving by train from evacuation hospitals near the battle lines at Chateau-Thierry and along the Marne River. Soon the hospital’s census exceeded seven hundred, most injured by gunshot and shrapnel wounds, with dozens of others suffering from poison gas.

To meet the growing number of casualties, two principal surgical teams were organized—the first under the command of Davis, the second under Charles Dowman. In August, a surgical team was deployed to staff Mobile Hospital 1, providing front-line care for American soldiers fighting in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the climactic battle to end the war. Twice during these final months, Base Hospital 43’s capacity was again increased to meet the desperate need; the day before the Armistice was signed ending the war, the hospital was serving 2,237 patients.

The Emory unit remained in France, caring for ill and wounded soldiers, until relieved from duty on January 21, 1919. They returned home to a rousing welcome at Camp Gordon that March.

Although the Emory unit received citations for meritorious service from General John Pershing, French Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch, and others, the greatest compliment may have come from a patient—a young Army lieutenant, E. H. Jefferies, from New York, who wrote: “Atlanta, you can be proud of Emory unit and if you think you have any more like it, send them along, but you have to go some to keep up with Emory. God bless the people of the South. From a Northern Yank.”

In September 1942, the Emory unit would be reactivated for service in World War II as General Hospital 43, serving in North Africa and France.