In Defense of Doubt

Last September, the clock ran down for Georgia death row inmate Troy Davis. But for defense counsel Jay Ewart 03L, troubling questions live on

The law says 'reasonable doubt,' but I think a defendant's entitled to the shadow of a doubt. There's always the possibility, no matter how improbable, that he's innocent.

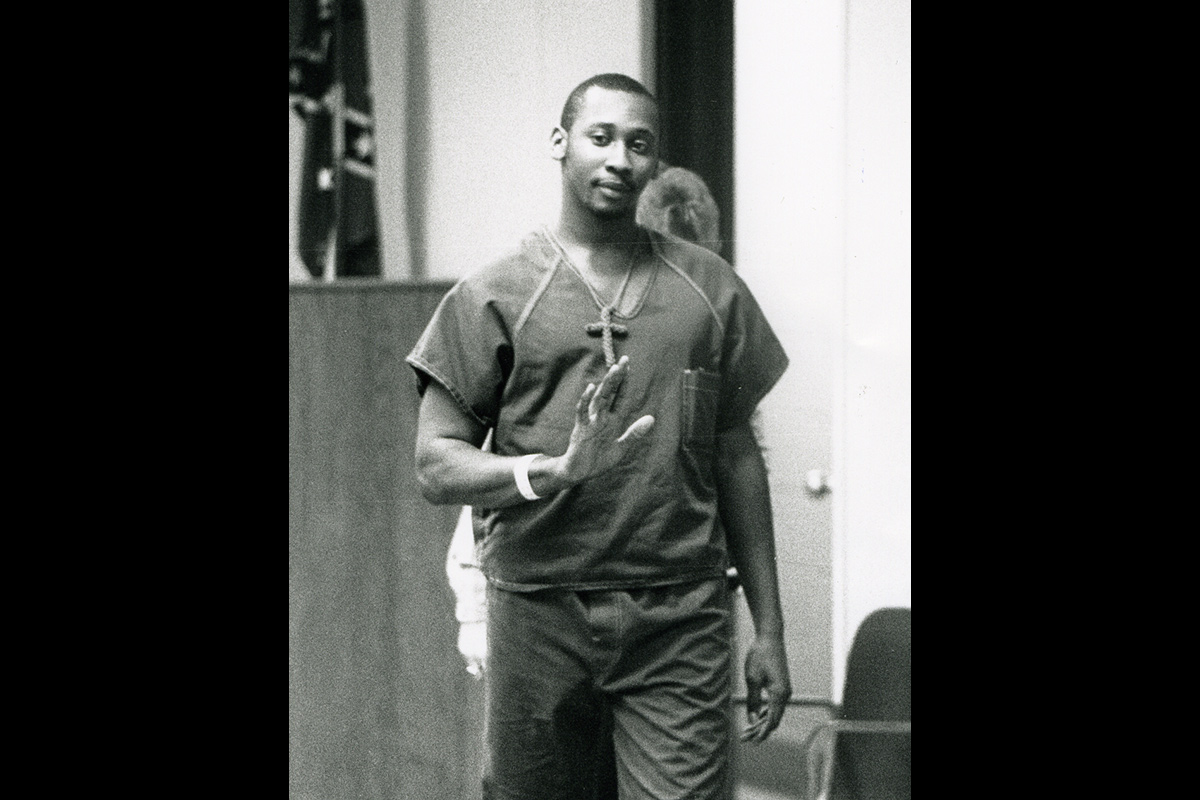

On the night that Troy Anthony Davis was put to death, a fierce protest roiled outside his maximum-security prison in Jackson, Georgia. More than five hundred Davis supporters marched, shouted, knelt, wailed, cried, prayed, and chanted, many holding candles or signs proclaiming, “I am Troy Davis” and “Not in My Name.” Rows of state troopers and police in full riot gear watched over the scene, stepping in when the action became too heated, as dozens of media outlets swarmed the crowd to get the story.

Smaller, but similar, demonstrations were taking place in Atlanta, Washington, D.C., and as far away as Paris, even as Davis’s legal team made a final, desperate appeal to the US Supreme Court.

And inside the prison, shut in a small, cinderblock room, Jay Ewart 03L was missing it all.

As Davis’s lead counsel and the only attorney Davis requested at the execution, that evening Ewart had to be segregated in a holding cell off death row, along with the prison chaplain. Only that morning he had woken up, head spinning with frantic determination, and called a friend who works at the White House to ask if maybe President Obama could make a call on behalf of Davis. Now, after working intensely for more than seven years to try to stave off Davis’s death, he spent these last four hours in relative calm—no cell phone, no computer, no legal appeals, no media, just the chaplain and the ticking clock.

Despite the highly charged atmosphere, Ewart had every reason to believe that Davis would still be alive when he left the prison that night. They had been in this position before: the scheduled execution, the last-minute appeals, and the ultimate reprieve. In 2007, Ewart’s legal team presented evidence to the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles that convinced them to grant Davis a stay within hours of the appointed execution time. The following year, the US Supreme Court stopped the lethal injection with less than two hours on the clock. In fact, last September 21 was the fourth time Davis’s death had been formally scheduled, and Ewart felt that the defense team had put on its strongest case yet.

So his main worry in those final hours was that Davis—who, after seven years, had become Ewart’s friend as well as his client—was strapped to a gurney and unable to move around.

“In 2008, I was in the same place, and that was an incredibly long shot,” Ewart says. “But things turned around, and we got to pack up and go home. We were ecstatic. I was sure we would get to turn around again.”

He was wrong.

Troy Davis grew up in Savannah in a mostly black, firmly middle-class neighborhood called Cloverdale. The eldest of five children, he was raised by his mom, who worked at a local hospital, in a well-kept red brick ranch.

News reports about the young Davis paint a blurry picture: his neighborhood nickname was “Rah,” short for “rough as hell,” and one teacher described a lackluster, lazy student. On the other hand, neighbors said he was a caring son and big brother who dropped out of high school partly to help drive a younger sister, who had multiple sclerosis, to physical therapy and school. Another sister, Martina, told a Savannah reporter that the Davises were a “unified family” raised in the church.

By 1989, Davis had earned his GED and was working off and on as a drill technician at a company that makes electric gates. He had one relatively minor criminal conviction on his record, but, at twenty, “He had plans,” Ewart says. “He was super involved with his family and would have stayed close to them. He probably would have gotten married, too.”

On the night of August 18, 1989, Davis and a friend went to a party in Cloverdale and then to a pool hall, winding up in the parking lot of a nearby Burger King. What happened then depends on whom you talk to, but what’s clear is that those moments altered the course of several lives. According to reports and eyewitness accounts, Davis came across two men who were arguing over a beer, and one began beating the other. That’s when Mark MacPhail, a police officer moonlighting as a Burger King security guard, stepped in. MacPhail, who was white, twenty-seven, and married with two children, was shot twice and died at the scene.

Davis quickly emerged as a suspect based on the stories of several witnesses, including one of the men involved in the parking lot fight. Ballistics evidence also indicated a possible link between the murder and another shooting that had taken place earlier in Cloverdale, near where Davis had been.

When Davis was brought to trial in 1991, nine eyewitnesses testified for the prosecution, saying they saw Davis shoot MacPhail or that Davis told them he did. He was convicted and sentenced to death in August 1991.

Davis maintained his innocence all along, testifying that he had fled the scene before the shots were fired. That’s the story he told the jury in 1989, the one he told Mark MacPhail’s family, and the one he kept telling anyone who would listen for the next twenty-two years.

Jay Ewart was a teenager in Springfield, Illinois, at the time of Davis’s murder trial. He describes his parents as dyed-in-the-wool sixties liberals who took their kids to Grateful Dead concerts. “I’m sure that’s about the only thing we could agree was cool,” he says.

Ewart’s dad is a lawyer who now works in Washington for the Coast Guard, helping to guide environmental cleanup; his mom is a teacher and librarian in Reston, Virginia. The family culture fostered an active awareness of social and political matters and a basic expectation of civic involvement. When Ewart served as a page in the Illinois senate, he blazed the trail for his brother and sister, who remember working there when Barack Obama was a senator.

Ewart also loved the book To Kill a Mockingbird, although he could hardly have imagined he would one day hand it to an African American man on death row in Georgia.

“I was extremely interested in politics as a kid,” Ewart says. “I thought if you are going to be a politician, you have to be a lawyer first.”

He pursued that path as an undergraduate at George Washington University, and then followed a girlfriend to Emory for law school. The relationship didn’t last, but Ewart thrived in his constitutional law courses and a clinic on civil rights cases, including a class taught by national capital punishment expert Stephen Bright. “Death penalty law is very constitution based. It’s essentially appellate work, habeas corpus work, where you have to allege there was a constitutional violation to get relief,” Ewart says. “My favorite classes were con law classes.”

So when Ewart took an offer to become an antitrust associate at the prestigious Washington firm Arnold and Porter, his parents were a little puzzled. “They were like, you’re going to go to work at a big corporate law firm?,” Ewart recalls. “Isn’t your biggest client tobacco?”

He managed to redeem himself somewhat when he joined some other associates working on a pro bono case in his first year—a practice supported by many law firms, although perhaps not to the degree Arnold and Porter demonstrates. Ewart was drawn to the Troy Davis case because of his connection with Georgia through Emory. Now, in addition to his day-to-day work on mergers and acquisitions, he had to get on familiar terms with a two-thousand-page, fifteen-year case transcript and Georgia criminal law.

Ewart first met Davis in 2004 on a visit to see him in prison. At that point, it didn’t seem as though Davis had much of a case left. He had been represented by the nonprofit Georgia Resource Center, an organization that provides legal representation to death row prisoners, but the office lost most of its federal funding and staff in 1995 and lacked the resources the case needed. Drawing on the center’s expertise in habeas corpus litigation—the legal mechanism that prevents prisoners from being held without cause—Ewart and colleagues from Arnold and Porter anticipated making one more routine appeal to Georgia’s eleventh circuit.

Still, Ewart was surprised by the determination he found in Davis.

“It was overwhelming to go down to death row in Jackson, Georgia, as a relatively young guy,” he says. “But Troy was very businesslike. He kind of just sat down and told us his story. It was amazing how much detail he had. I still have the maps he drew me to show where things happened, where he was. Troy was a talker. If we ever got him started on that night, he would go on for an hour and tell us everything again.”

Davis was convicted of murder largely due to dramatic eyewitness testimony at his initial trial. There was no physical evidence, no DNA, no murder weapon. But an African American man was accused of killing a white cop, and Savannah was in an uproar. Few observers deny that racial bias, combined with outrage over the loss of a promising young police officer and family man, probably bolstered the district attorney’s otherwise rickety case.

Anne Emanuel 75L teaches criminal law and procedure at Georgia State University and followed the Davis case closely. “I think one of the most disturbing things about this case is that it was a lousy case for the prosecution from the beginning,” she says. “The evidence at trial was a combination of highly questionable eyewitness identification and hearsay confessions. Race was most likely a factor because tensions were high in Savannah in 1989 and made this a very highly charged incident.”

Michael Leo Owens, Emory associate professor of political science, agrees. “This was a classic issue of black offender and white victim,” he says. “Studies tell us that when you have that scenario, the likelihood is that the black offender is going to be found guilty.”

When Ewart got involved some fifteen years later, it seemed fairly clear that regardless of the facts of the case, Davis had been carried to death row on a wave of something like modern-day mob fury. But as a defense attorney, facing a death penalty conviction is a little like losing your queen early in a chess match: you’re at a crushing disadvantage for the rest of the game. Saving Davis’s life was no longer a matter of creating reasonable doubt about his guilt—it required definitively proving his innocence. And as time passed, that possibility slipped further and further out of reach.

Still, during the next couple of years, Ewart and his team, working alongside the Georgia Resource Center, managed to build an impressive amount of traction around Davis’s case.

“Jay is someone who learns very quickly, and he brought a level of intelligence and commitment to the case that was admirable,” says Brian Kammer, executive director of the Georgia Resource Center. “He showed tons of energy and drive and creativity.”

The breakthrough development in their favor was that witnesses began backing off their original testimony—not just one or two, but ultimately, seven out of the nine key eyewitnesses from the original trial recanted. In addition, retesting of the bullets from the two shootings that August night cast serious doubt over the connection that had been established at the initial trial.

The 1989 proceedings were a complex tangle that included some seventy witnesses, but Ewart recognized the need for a clear defense strategy that the courts and the public could grasp quickly.

“Out of nine key witnesses, seven recanted. There was no physical evidence. They never found a murder weapon,” Ewart says. “That became our mantra. We started repeating it, over and over, thousands of times. And people started listening and saying, you know, that gives me pause.”

At the same time, after years of relative obscurity, Davis’s sister Martina began a calculated campaign to drum up some attention for her brother. She contacted Amnesty International, an organization with considerable media savvy, and the NAACP became interested as well. A groundswell of awareness and support began to build.

By 2007, Davis’s defense team believed they had amassed some new and compelling evidence. But they were facing steep legal obstacles, including restrictions created by the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act. Spearheaded by former House Speaker Newt Gingrich 65C in 1996, the law was enacted in the wake of the Timothy McVeigh trial to shorten the lengthy march from death sentence to execution by eliminating some of the options for appeal—such as the presentation of new evidence. Davis’s case, from a legal standpoint, was all dressed up with no place to go.

After a request for a new trial was rejected by Georgia’s eleventh circuit, Davis was scheduled for lethal injection in July 2007. Less than twenty-four hours before, in his first real hearing as an attorney, Ewart faced the final frontier for death penalty defense: the Georgia Pardons and Parole Board.

The surprising seven-hour hearing, with statements by five witnesses—four of whom were changing their original stories—was “the most intense thing I’ve ever seen,” Ewart says. “It was a giant event media-wise and for me as a young attorney, it was a little scary. The board was very upset that all this evidence had just come in front of them. The witnesses were incredibly convincing. They granted us a stay at the very last minute.”

The following year—on the eve of a second execution date—Davis’s team appealed to the US Supreme Court, arguing that it would be unconstitutional for the state to execute Davis if his innocence could be proven. The high court eventually agreed. For the first time in more than half a century, a death row inmate would be given the chance to prove his innocence. But, Ewart says, “The bar of burden of proof was monumentally high.”

At the penultimate hearing in 2010, Davis’s defense put up what they believed to be a rock-solid case. But some of the same factors that had worked against Davis in the first place continued to hold back the defense: weak ballistics conclusions, the lack of physical or DNA evidence, and shaky witness testimony. Two of the strongest recanting witnesses from the 2007 hearing were unable to attend in 2010, and statements from some of the other witnesses lacked the conviction they previously carried.

“One of the hardest things about this case was that Troy had been pushing for an evidentiary hearing ever since 1997, but it was denied until 2010, and then the argument was that it had been too long. People’s memories fade,” Ewart says. “It was really disappointing because our testimony in 2007 was better than in 2010. That kind of delay hurts everyone.”

Ewart was devastated when the US District Court upheld Davis’s conviction—a blow that pushed Davis several steps closer to the death chamber. When his execution was scheduled once again last September, the defense team lost their appeal to the Pardons and Parole Board by a vote of three to two. A final plea to the US Supreme Court was rejected four hours after the official execution time.

“It is certainly true that it is extremely difficult to try to get a conviction overturned based on new evidence,” says Robert Schapiro, interim dean of Emory’s School of Law. “I believe Jay did a remarkable job of forcing the courts to take another look at the Troy Davis case and to bring public attention to the problems of using the death penalty in situations where the underlying facts are subject to serious dispute.”

Most state executions attract media attention and objections from anti-death penalty blocs, but the circumstances of Davis’s case raised broader, more serious concerns about the law and the legal procedures that led to his death.

In the days before last September 21, public disquiet mounted to a fever pitch. Nearly a million people worldwide signed an Amnesty International petition to halt the planned execution. A wide-ranging assortment of high-profile figures came out with statements against it, including several with Emory connections—former US President Jimmy Carter and author Salman Rushdie, both University Distinguished Professors; alumnae band the Indigo Girls; and former Commencement speaker Archbishop Desmond Tutu, as well as luminaries such as former President Bill Clinton and Pope Benedict XVI.

“If one of our fellow citizens can be executed with so much doubt surrounding his guilt, then the death penalty system in our country is unjust and outdated,” Carter said in a statement. And Rushdie declared via Twitter, “As an honorary citizen of the state of Georgia and professor at Emory University, I appeal to Georgia not to execute Troy Davis.”

Most of the protest centered on the doubt that Ewart and his colleagues had generated about Davis’s guilt during the past several years. In 2008, when the Georgia Supreme Court turned down an appeal for a new trial in a close four-to-three vote, Chief Justice Leah Sears 80L summed up the legal concerns in a dissenting opinion.

“In this case, nearly every witness who identified Davis as the shooter at trial has now disclaimed his or her ability to do so reliably,” Sears wrote. While recantation testimony is acknowledged to be legally problematic, “If recantation testimony, either alone or supported by other evidence, shows convincingly that prior trial testimony was false, it simply defies all logic and morality to hold that it must be disregarded categorically.”

For Emanuel, the Davis case highlighted troubling problems in the system that she uncovered in 2006 when she chaired an American Bar Association (ABA) committee appointed to evaluate the fairness and accuracy of the death penalty in Georgia. The committee reported a number of shortcomings in death penalty procedure—most notably that representation for criminal defendants at trial is often inadequate, and that there are increasing obstacles to their access to habeas corpus.

“I trust there is actually broad agreement with the ABA position, which is simply that justice requires the use of the death penalty to be accurate and fair,” Emanuel says. “But even though virtually every study finds serious problems, to a surprisingly great extent they go unaddressed. For too many people, who should be executed is just about the only thing they trust the government to always get right.”

Kammer, of the Georgia Resource Center, calls Davis’s execution “a constitutional and moral disaster that exposed the flawed and broken nature of the death penalty system, not just in Georgia, but all over the country.”

If part of the purpose of the death penalty is to deter crime, many of those who oppose it cite widespread evidence that it doesn’t, at least not to a meaningful degree. But some experts contend otherwise—including a trio of Emory professors who published a paper on the subject in 2002. Hashem Dezhbakhsh and Paul Rubin of the Department of Economics and Joanna Shepherd Bailey of the law school did a national empirical analysis to conclude that capital punishment has a “strong deterrent effect,” with every execution resulting in eighteen fewer murders. The findings are hotly disputed by death penalty opponents and some legal scholars, who find significant fault with the study’s methodology.

In a subsequent and more targeted review, Shepherd Bailey found that the level of deterrence varies widely from state to state, with the strongest effect in states that execute high numbers of prisoners. Of the thirty-four states that allow for capital punishment, she found that it deters crime in only six; in the others, it has no effect, or may actually increase the murder rate.

In other words, she says, the death penalty is only effective in states that actually carry it out—Texas being the leader, with 477 executions since 1976; Georgia is number seven.

“Overall, the effect is driven by a few states,” Shepherd Bailey says. “California has the largest death row in the country, but they have only executed thirteen people since 1976, so the law does not have the same bite.”

The debate over capital punishment in the US rolls on, but for Davis, time ran out. Without definitive proof of his innocence, his defense was left without options and the state had an obligation to forward, Ewart says.

Ewart remembers Davis as a thoughtful man with a curious mind and a memory for detail. In prison, he was an avid reader and a prolific letter writer, and he enjoyed talking with Ewart for hours on subjects ranging far beyond his case—especially his family, to whom he remained devoted. Ewart spent long hours on the phone with Troy and also with his sister Martina, his staunchest advocate, who died of breast cancer in December.

Early in their acquaintance, Ewart gave Davis a copy of To Kill a Mockingbird. The next time they met, Davis was ready to talk about it.

“Troy reminded me of a part when Atticus Finch is talking about the death penalty, and he says, I just don’t believe in it unless there is no shadow of a doubt. I thought he was very keen to pick up on that,” Ewart says. “When I saw Troy die, I felt like I was watching not only the untimely death of a client, but also a friend.”

Now Ewart is consumed with a heavy workload and is considering his next pro bono case. Still, Davis is never far from his mind.

“It’s strange, because I still think about the case constantly,” he says. “I’ll have an idea for a new strategy, and then I’ll kind of wake up and remind myself that Troy’s dead, it’s over. Luckily they haven’t been great ideas so far. I have to hope I don’t get one.”