When Miracle Drugs Stop Working

An Emory researcher's drug resistance index helps track trends

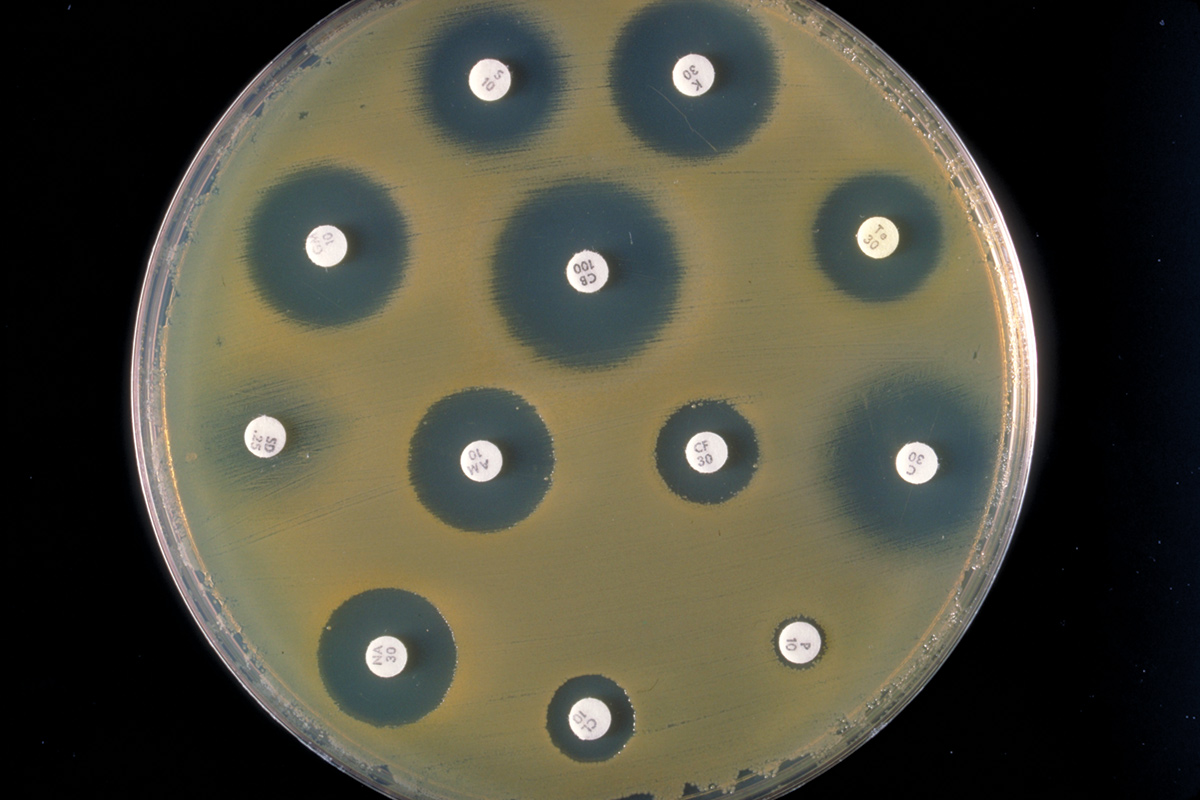

CDC/Dr. J. J. Farmer

When penicillin was first sold as a drug in the 1940s, it was seen as a miracle, able to cure illnesses from pneumonia to syphilis and to ensure that a scratch on the finger rarely turned fatal. Plentiful access literally created a leap in life expectancy. Tetracycline followed, and then amoxicillin.

Now, however, the stark reality is that we are “on the brink of losing these miracle cures,” warns World Health Organization (WHO) Director General Margaret Chan. “We have taken antibiotics and other antimicrobials for granted. And we have failed to handle these precious yet fragile medicines with appropriate care.”

The culprits: patient demands, lax prescribing practices, poor infection control in hospitals (already hotbeds of antibiotic-resistant pathogens), weak drug regulation, and industrialized food production practices. Resistance is spreading faster than research and development of new medicines.

To help prepare for future problems, Emory’s William H. Foege Chair of Global Health Keith Klugman, president-elect of the International Society for Infectious Diseases, and Ramanan Laxminarayan of the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics, and Policy in Washington, D.C., have developed a novel index for tracking resistance, as reported in the British Medical Journal Open.

Similar to a consumer price index, the drug resistance index (DRI) gathers information about resistance and antibiotic use patterns to illustrate trends in antibiotic resistance over time and across regions. The DRI is designed for application at any level, from local to national. It can also be used by hospitals to track their own resistance levels and intervention success.