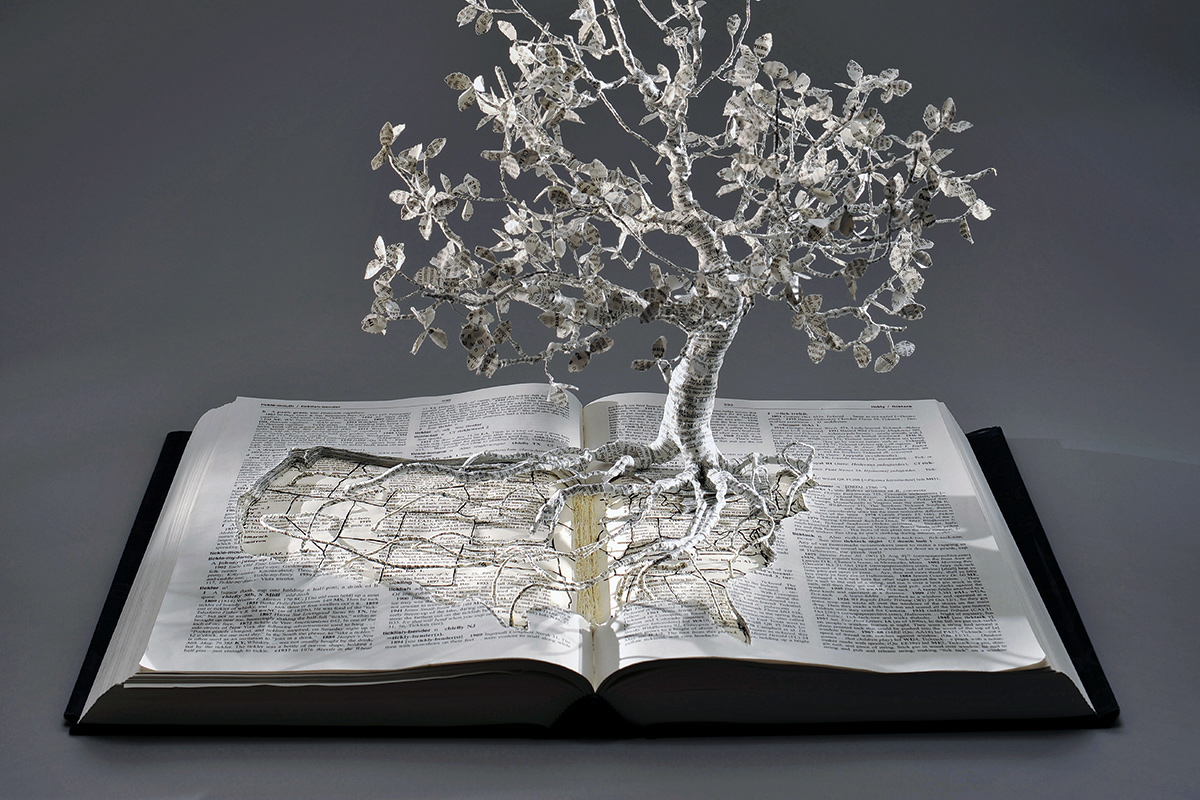

Fantasy Realms

A Hospital Janitor's Extraordinary Art

Coming up: Moon's next project is on director Pier Passolini's film Arabian Nights.

Emory Photo/Video

Consider the case of an artist who lived in an asylum for “feeble-minded children” in Lincoln, Illinois, in the latter part of the nineteenth century and whose adult work—literary and visual—depicted horrific violence toward children, especially girls. It seems a sure-fire recipe for obscurity and societal rejection, yet some works by Henry Joseph Darger Jr. (1892–1973) now sell in the $80,000 range. He has attracted the deep interest of Michael Moon, professor of American Studies in Emory’s Graduate Institute of Liberal Arts and in the Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies.

Little is known of Darger’s life. The three extant photographs of him hardly would fill out an album. He spent his youth in a series of Chicago-area orphanages and mental institutions. At seventeen, Darger ran away from his last institution, eventually finding work as a hospital janitor. For the next sixty-four years, Darger would pick up trash during the day and create art at night, telling no one of his labors and mentioning them only once in his unpublished five-thousand-page autobiography.

According to Kevin Lewis of Documentary.org, “When ill health finally forced Darger from his apartment in late 1972 . . . , [his landlord Nathan] Lerner found narrow footpaths leading from door to bed to bathroom through ceiling-high mounds of paintings and typed texts and scrap images. . . . Lerner was . . . an artist in his own right, and he immediately recognized something extraordinary in Darger’s piles. When he saw Darger in the charity ward shortly before he died, he told him so. Darger could only mouth the words, ‘too late.’ ”Does Darger warrant all the privileges and burdens of the term outsider artist? Michael Moon says no. Before authoring Darger’s Resources (2012), Moon published A Small Boy and Others: Imitation and Initiation in American Culture from Henry James to Andy Warhol (1998). In that book, Moon delved into the careers of Joseph Cornell and Andy Warhol, two “visual artists who had left vast archives of writing that no one seemed to have much of a notion of what to do with.” Says Moon, “I had no idea when I finished my second book that my third would be about Henry Darger, but it makes a certain kind of sense looking back. I was not writing a study of an outsider artist as such. I was writing about another one of these artist-writers.”

Darger is the author of the fifteen-thousand-page, twelve-volume The Story of the Vivian Girls in What Is Known as the Realms of the Unreal of the Glandeco Angelinnian War Storm as Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion, which is often mercifully shortened to In the Realms of the Unreal. Moon first encountered Darger’s work in 1998 at an American Folk Art Museum exhibition.

According to Moon, the character of Darger’s writing is “appropriative in the extreme,” sometimes reproducing entire chapters of others’ works, such as Pilgrim’s Progress. Moon notes, “Darger’s inner child is not ‘inner’ in the writing; it is a strange, weird, and fascinating combination of Uncle Wiggly–like tales and a child reader delighting in giving the story and language all the twists and turns he could give it.” The pages also are replete, says Moon, with “puns and silly jokes—the things that most adults edit out of their writing and out of their very being.”

About twenty years into writing, Darger started to make elaborate visual art, which resulted in hundreds of paintings. He is a sophisticated artist, recalling masterworks such as Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Massacre of the Innocents at the same time as he borrows from coloring books, comic strips, newspapers, and magazines. Moon explains that Darger spent from roughly 1908 to around 1938 “writing a vast narrative about pious little girls drawn into a war over slavery, and . . . then spent even more decades ‘sequelating’ the work by illustrating it.”

Darger has been demonized as a possible serial killer in speculation that erupted after John MacGregor—an art historian and former psychotherapist—published In the Realms of the Unreal in 2002. Salon author Gavin McNett falsely claimed that the Lerners found in Darger’s room “the skulls and tibiae of several little girls, polished as though by long fondling.”

Moon takes a more empathetic view, alleging that Darger “took on the role of witness to the terrible ordinariness of violence in the history of the twentieth century—especially violence against children, and specifically against girls.”

Moon, who teaches a course on graphic novels, says his own childhood interests included Batman, Superman, and the lives of the saints. Moon recalls that he, like Darger, didn’t observe distinctions between high-, middle-, and lowbrow literature. “For me,” he laughs, “the distance between a superhero and a Christian martyr was pretty much the same.”

As the world continues to debate and enjoy Darger’s art, Darger himself is buried in a pauper’s grave in Des Plaines, Illinois. His headstone is inscribed “Artist” and “Protector of Children.”