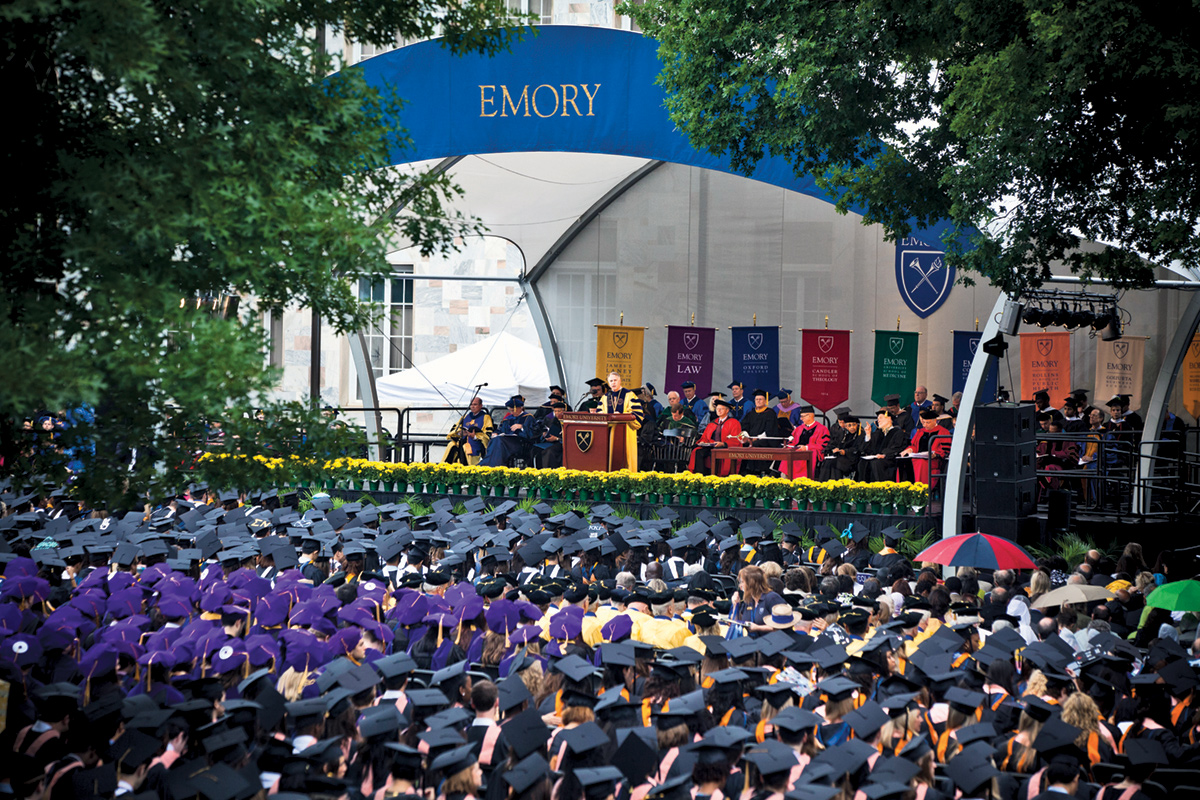

Customized Care

Emory's Predictive Health Institute is prolonging healthy lives, while saving money

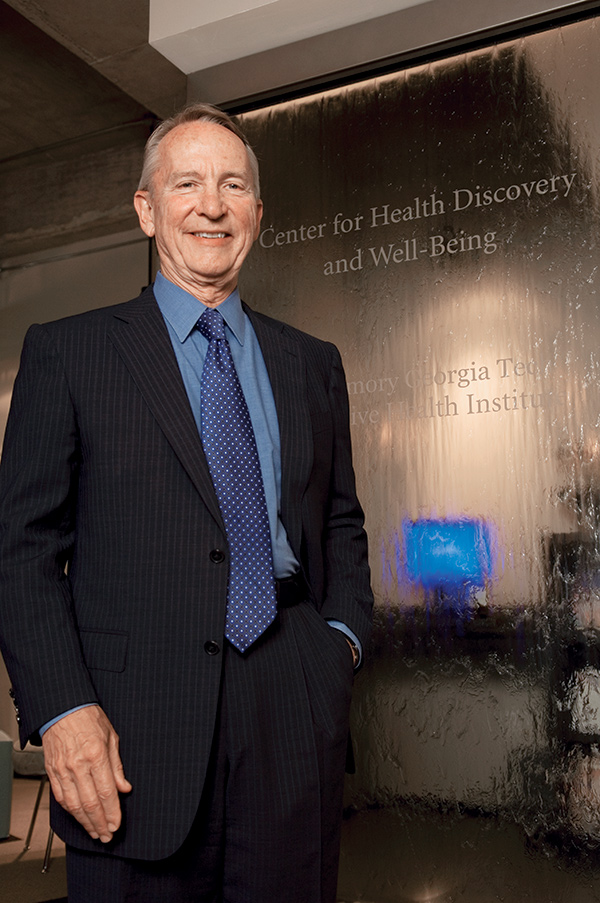

Ken Brigham

Emory Photo/Video

The future of health care, so often portrayed as troubled, could instead produce better outcomes for lower costs. And who would argue with that?

Providers would take into account not only your gender, age, and family history, but also your genetic predispositions and environmental risk factors.

Before you were even sick, you would sit down with a health care “coach” who would work with you on staying healthy and becoming even more fit, helping you establish a diet and exercise plan.

Your odds of developing common diseases, from diabetes to breast cancer to Alzheimer’s, would be determined and preventive steps taken.

At the Emory-Georgia Tech Predictive Health Institute (PHI), where the focus is on maintaining wellness rather than treating disease, this forward-thinking health care is already standard practice.

Through blood work, stress tests, biomeasures, and self-report surveys, the PHI can measure each patient’s deviations from a healthy norm. Such information gives practitioners a head start on potential problems.

“We aim to intervene at the very earliest indication, based on an individual’s personal profile, and restore normal function,” says PHI director and Associate Vice President Ken Brigham.

A random sample of seven hundred Emory employees were enrolled in the center’s predictive health program through the Center for Health Discovery and Well Being at Emory’s Midtown Hospital in 2008 (including Emory Magazine editor Paige Parvin), and it was a nearly universal success.

The cross-section of employees started out “looking very much like America,” says Brigham: two-thirds were overweight (one-third obese) and a number had high blood pressure and cholesterol levels.

Participants filled out computer-based questionnaires and surveys about their health, and underwent various tests and measurements including body fat composition, blood pressure, pulse, and blood and urine samples. Bone density and cardiovascular fitness were measured. At the end, the participants received a forty-page health assessment; half were assigned a health partner for guidance and support.

Results during follow-up appointments were positive across the board, especially for those with health partners: a reduced risk for diabetes and heart disease, weight loss, a decrease in fasting blood sugar and cholesterol, and a decrease in inflammatory markers. Even more exciting, signs of well-being increased: stress and depression levels were down, sleep quality and other quality-of-life indicators were up.

“Regardless of what patients decided to work on, everything seems to go together,” says Brigham, who is seventy-two and went through the program himself. He saw his heart disease risk decrease by 40 percent after a year.

Professor Bill Rouse of Georgia Tech analyzed data from the PHI study using risk models developed by Peter Wilson of Emory’s School of Medicine based on the Framingham data set. Rouse says the program is “having an enormous impact on a substantial portion of the population at high risk for diabetes and heart disease. These interventions are substantially lowering these people’s risk of the diseases and extending their healthy lives.”

After reviewing the Emory claims data of more than sixty thousand insured patients, Rouse says, “I know what a diabetic patient costs Emory. And they are saving a considerable amount of money in health care costs they would have incurred.”

The PHI also hosts a predictive health symposium in Atlanta each year and is developing a curriculum for a health partner certificate program through Continuing Education.