How Salman Rushdie (Finally) Wrote a Memoir

Born-digital materials are reshaping memory and the creative process

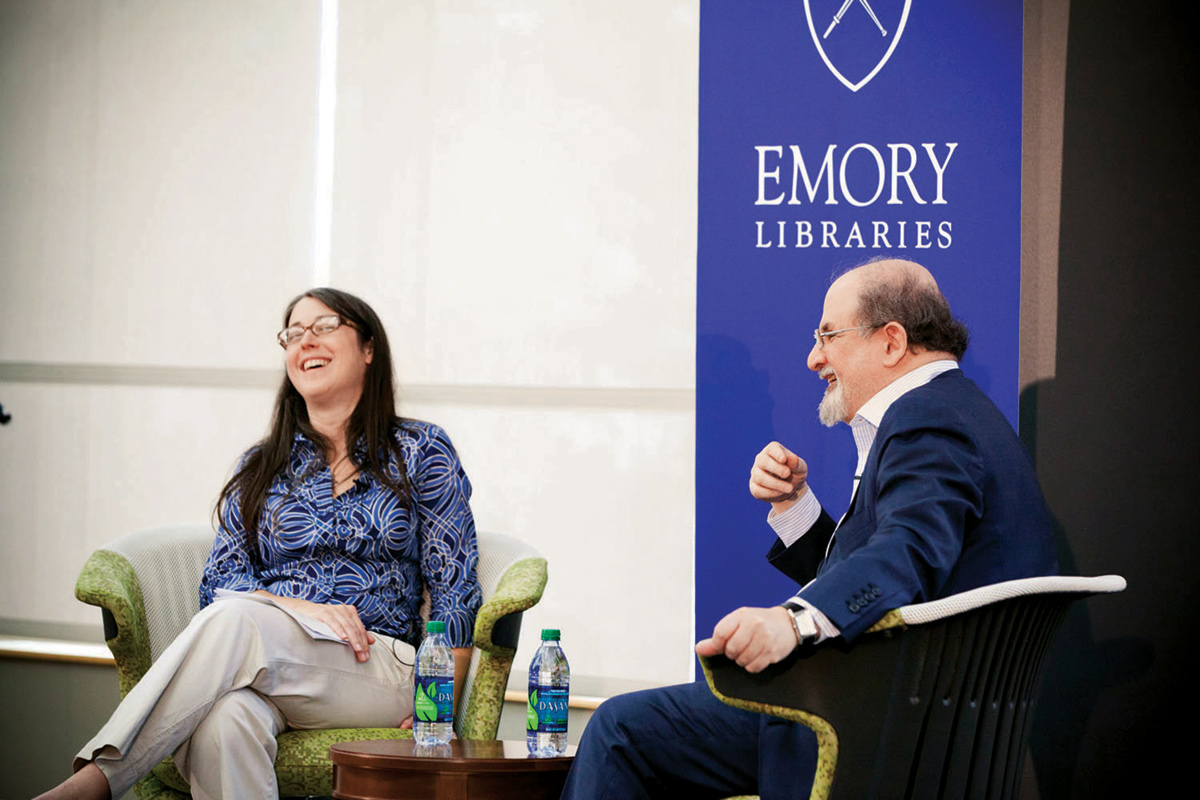

Bryan Meltz

When Salman Rushdie granted Emory his archive—records that capture four decades of his literary life—he wasn’t just opening the door to public examination of a writer and his creative process.

Organizing his life’s writings, which range from scribbled notes and faded faxes to computer files, also made it possible for the award-winning author to tackle in-depth research for a new book—an autobiographical memoir.

Emory’s archives “actually allowed me to write the memoir,” says Rushdie, speaking in March during discussion at Woodruff Library on how digital scholarship has shaped his craft. The event was one of a series of programs and appearances scheduled during his recent two-week visit as University Distinguished Professor.

“People had been asking me [to write it] for a very long time, but I just didn’t feel ready,” he says of the long-awaited book, Joseph Anton: A Memoir, scheduled for release by Random House in September. It is anticipated that Rushdie will reflect at length upon little-discussed years of seclusion (as Joseph Anton) after his novel The Satanic Verses earned him death threats from Islamist extremists in 1989—a cloud that wasn’t lifted until 1998.

When President James Wagner invited Rushdie to entrust his archive to Emory eight years ago, the author said that decades of writing had been hastily stuffed into cardboard boxes in the attic— “a complete mess,” Rushdie admits. “There was no organization—a hundred boxes of everything and I didn’t even know what was there.”

Working with Emory’s Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL) to catalogue his writings yielded a valuable resource when Rushdie began work on his memoir, which is reportedly more than six hundred pages. Through the digital archive, he was able to consult a master index within a searchable database—”my life with barcodes,” he joked—to confirm details that might otherwise have been lost.

Human memory is fickle and unreliable, Rushdie acknowledged, and he could not have written a memoir without the aid of the archive. But he also said that he doesn’t plan to spend a great deal more time with it, as his “instinct is to not look backward.”

“Memory has a way of telling you what’s important,” he says. “Yes, this archive is nostalgic for me, and in the specific case of the memoir I was going back to try to create, it was essential.”

Fittingly, Rushdie’s public conversation with Erika Farr, coordinator of digital archives in MARBL, took place in the libraries’ new Digital Scholarship Commons (DiSC), designed to help faculty and graduate students harness digital tools and resources at Emory to create powerful and engaging scholarship. DiSC is the flagship tenant of the new 4,500-square-foot Research Commons on the third floor of Woodruff Library.

“Just as we see the university library as the intellectual commons of the university, we see our Research Commons becoming a transdisciplinary bridge between the humanities and social sciences, connecting faculty, students, the campus, and the community in new and different ways under this digital flag,” said Vice Provost and Director of Libraries Rick Luce at the grand opening of DiSC in February.