Moving the Needle

A national opioid epidemic is driving people from pills to heroin, filling emergency rooms with overdose cases, and killing tens of thousands of Americans every year. What are we doing about it?

When "Stacy" (whose real name is withheld for patient privacy) and her husband moved to Atlanta so that she could begin a PhD program at Emory's Laney Graduate School, they weren't familiar with the city, and they needed an affordable place to live.

They wound up renting a house "for really cheap" in what turned out to be a neighborhood hub for heroin distribution. That was bad luck, since Stacy's husband was already recovering from heroin addiction. When dealers started knocking on the door, it wasn't long before he caved. And then Stacy began injecting heroin, too.

"It was hurting our relationship," Stacy says, "so I started using just to be on the same page."

And then, well, there was the high.

"You get a rush immediately, within five seconds," she says. "After that, for the next twelve to twenty-four hours, you just feel really calm and peaceful. There are still moments of euphoria, but the reason I liked it so much is that it's really numbing. Anything that you're anxious about just doesn't matter anymore, which is useful in graduate school. It gave me a lot of energy and motivation. I had no problem coming to school and doing what I needed to do."

At least for a while.

Unlike an estimated 80 percent of heroin users, Stacy had never taken prescription opioids. But she's part of a sweeping epidemic of opioid use that has grabbed national attention, partly because people are dying in increasing numbers.

Emory President Claire E. Sterk is leading a strong and definitive response by the university. In January, she kicked off a public discussion about the epidemic—the second of Emory's "Conversations with America" series, an effort to advance and promote dialogue around national issues conducted in collaboration with nationally renowned NBC/Wall Street Journal pollster Peter Hart.

As a social scientist and public health expert, Sterk has spent decades working on major public health issues that have included addiction and HIV/AIDS. The current crisis, she says, calls for both action and compassion.

"I come from a culture that strongly believes in the philosophy that if somebody has a problem with opioids, the last thing we should do is blame them and turn him or her into a criminal," said Sterk, who is also Charles Howard Candler Professor of Public Health. "Because at the end of the day, addiction is a societal problem—it's a problem for all of us. We collectively are responsible for not stigmatizing people, for thinking about solutions, and for having these kinds of conversations."

One of the featured speakers was Debra Houry, director of the CDC's National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and a former associate professor in Emory's Department of Emergency Medicine. About three years ago, Houry took on a CDC project to outline a set of guidelines that advocate prescribing non-opioid medications for chronic pain first.

"My concern is that we primed the pump, so a lot of people became addicted to prescription pills and have then gone on to misuse heroin and now fentanyl, which we know is killing people due to its potency," she said.

Wake-Up Call

Why do people keep using a drug that they know could kill them?

In a word—dopamine.

When an opiate travels through the bloodstream and reaches the brain, it latches on to receptors that normally release an acid called GABA. Part of GABA's job is to regulate the presence of dopamine, so when it's suppressed, dopamine becomes much more available. The drug also grabs onto opioid receptors in a different region of the brain that increases dopamine release. Opioids are enough like the chemicals produced naturally in the brain that they are able to fool these receptors into opening their microscopic doors, kind of like the big, bad wolf dressed up in grandmother's nightie—and just as ready to eat you up.

Dopamine is the ultimate feel-good neurotransmitter, a biochemical wellspring of pleasure and reward; there's a reason why our brains are wired to regulate it in the first place. When it's given too much freedom, we can't respond to pain appropriately, feel normal levels of anxiety, or accurately anticipate the outcome of decisions.

If used habitually over time, opioids can essentially overwrite and reboot the reward system in the brain, similar to installing a new operating system in a computer. And if the opiate of choice is, say, heroin—that also happens to be laced with the popular, super-potent additive fentanyl—pretty soon the user is no longer chasing that early, soaring, euphoric high, but the new normal, a bar that's constantly being raised by the chemical change taking place upstairs.

"Opioids are tied in with the dopamine system, and they augment that system tremendously," says Brent Morgan, professor and vice chair of Emory's Department of Emergency Medicine. "People get rewired in a way that causes extreme cravings. They need more and more of the drug to manage the cravings and the withdrawal symptoms."

The first time Stacy experienced withdrawal, late in fall semester of her second year at Emory, "It caught me completely off guard. People describe it like the flu, but it's more the mental part, the worst combination of depression and anxiety," she says. "I had suicidal thoughts, which I never have, and I had to walk to our dealer's house in withdrawal. It was the worst thing ever."

Opioid withdrawal isn't the most dangerous kind of substance withdrawal, says Morgan; it just feels the worst. "Because of the receptor changes and brain pathway changes, withdrawal can cause incredible dysphoria, with feelings of dread and impending doom," he says. "People feel like they are going to die."

It is one of the many ironies of opioid addiction that when users think they're going to die, they're probably not; it's when they feel near-immortal that they're in real trouble. According to the CDC, overdose has been climbing at an alarming rate since around 2013, when a surge of illegally produced fentanyl started showing up in street heroin and sending people to emergency rooms in droves.

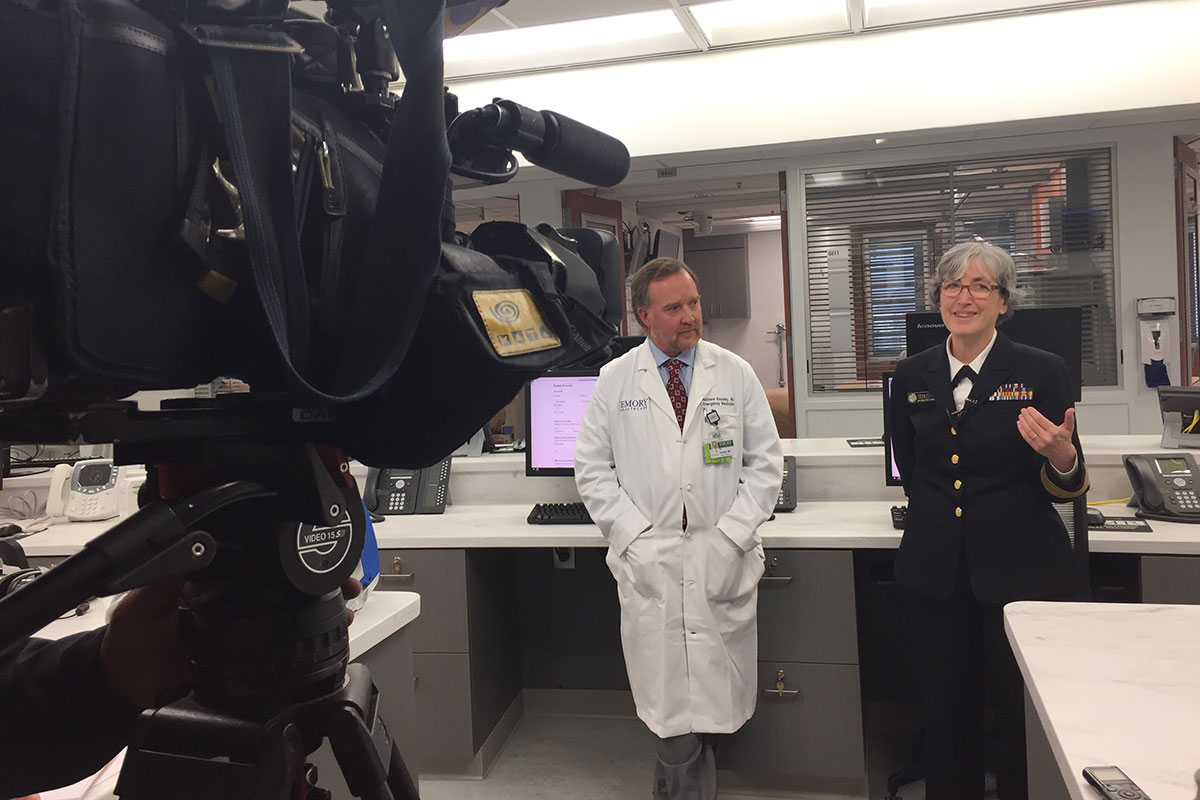

The crippling drain on emergency care was the topic of a press conference at Emory University Hospital in March, where Matthew Keadey, associate professor and chief of emergency medicine, appeared with CDC acting director Anne Schuchat to share grim news: The latest national data show that ER visits from opioid overdoses rose 30 percent from July 2016 to September 2017.

"We see it on a daily basis," Keadey said. But as the problem escalates, so does the response. In 2016, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) launched an Opioids Action Plan, asking the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to convene a committee to review the science on pain research, medical care, and education, and to identify actions the FDA and others can take.

Anne Marie McKenzie-Brown, associate professor of anesthesiology and director of the Emory Pain Center, was selected to serve on the committee, which released a report last summer outlining some strategies for physicians.

"The FDA asked us to balance the need for pain relief while contrasting the growing problems related to opioid overuse and abuse," says McKenzie-Brown. "Focusing on the individual benefits versus the risks of prescription opioid use is going to take a culture change."

Emory/CDC Combine Forces: Matthew Keadey (left) and Anne Schuchat met in March with reporters at Emory University Hospital to talk about ways to combat the opioid crisis, which has been declared a public health emergency.

Janet Christenbury

The opioid crisis is now a federal public health emergency, and concern in Congress is crossing the aisle with legislation pending in both the House and the Senate. Proposals include expanded access to clinical treatment as well as defined best practices for prescribing health professionals.

And last year, Georgia lawmakers approved a new Prescription Drug Monitoring Program to help physicians track patient prescriptions. The Georgia Department of Health now oversees the database, with the involvement of stakeholders in Emory Healthcare. The next step, says Keadey, is tightening communication across state lines.

Morgan, assistant medical director of the Georgia Poison Center, shares the concern that opioids legally prescribed for pain are part of the problem, because they quickly recalibrate the brain chemistry just enough to leave patients needing more. Some 80 percent of heroin users report taking prescription opioids before they no longer have access and turn to the cheaper, riskier option."Heroin can be a lot more potent, especially when it's cut with fentanyl, which we're seeing much more frequently," Morgan says.

Another irony of opioid use is how fast the ultimate high can turn to the ultimate low. The receptors in the brain that the drug binds to are the same ones that control breathing, so when users miscalculate and overdose, they can literally forget how to breathe.

"Overdosing patients can go into a coma so deep that it shuts down the brain's ability to tell the lungs to move," Morgan says. "The lack of oxygen and the buildup of carbon dioxide are what cause most overdose deaths."

As those deaths increased in recent years, so did the level of frustration for Morgan and his colleagues at Grady Memorial Hospital, where he says roughly 25 percent of emergency overdose cases are due to opioids.

"People were coming in with an overdose, and we could revive them, but then we didn't really have much to offer them," Morgan says. "So we decided to open up our own treatment program."

With the help of a grant from the state, last August they launched Grady's Medically Assisted Opioid Program. The comprehensive outpatient program includes treatment with buprenorphine, a drug similar to methadone, as well as individual and group therapy.

Now, when the emergency department releases a patient after opioid overdose, they have somewhere to send them. With thirty patients, the program has fulfilled the initial grant, and Morgan expects the funding to continue. "It will benefit the system overall," he says.

New Treatment Option at Grady: Frustrated with reviving overdose patients and simply releasing them, physicians and nurses at Grady Memorial Hospital created an outpatient treatment program.

Andy Gish 06N knows firsthand just how much. As an emergency room nurse at Northside Hospital, Gish began to note an uptick in opioid overdose cases as far back as ten years ago.

"A lot of them were in bad shape," Gish told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in a video interview for the 2018 "Celebrating Nurses" series. "A lot of them weren't waking up."

Gish began to get involved with the issue, spending more and more personal time educating people about opioid use. As a volunteer with Georgia Overdose Prevention and the Atlanta Harm Reduction Coalition, Gish works with opioid users to show them how and when to use naloxone, the overdose-reversal drug sold under the brand name Narcan.

In 2014, Gish testified before Georgia lawmakers in support of legislation that put the state ahead of most others with passage of a medical amnesty law. She is now able to tell people with opioid use disorder that the "Don't Run, Call 911" law provides limited immunity from arrest and prosecution for individuals seeking medical help—for themselves or others— in cases of overdose. The law also expands access to Narcan, allowing any Georgia resident to purchase it at a pharmacy.

The former president of her class at Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Gish now teaches classes on addiction to Emory nursing students. She lives in a high drug use neighborhood similar to the one Stacy and her husband landed in, where she teaches people on the street how to use Narcan and hands it out.

Recently, she gave a supply of the drug to a restaurant manager, and within two weeks, the manager used it to save a life in the restaurant bathroom.

"You don't have to die of an overdose," Gish says. "If naloxone can be given quickly, literally nobody has to die."

Front Lines: Emory faculty (from left) Justine Welsh, Mark Wilson, and Brent Morgan are addressing addiction in multiple ways, through intensive therapy, innovative research, and dynamic treatment protocols.

Kay Hinton

Building Knowledge Through Science

To understand addiction, experts across Emory have explored the ways the brain responds similarly to different substances that can lead to unhealthy habits and dependence. For instance, food.

Mark Wilson is a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and a researcher at Yerkes National Primate Research Center. His lab studies nonhuman primates to learn about behavioral endocrinology, specifically how social factors and endocrine signals combine to drive behavior.

In one widely publicized study, Wilson and his colleagues used food to examine the effects of social stress on rhesus monkeys, and whether it's likely to lead to addictive behaviors. The monkeys live in strictly hierarchical groups, organized from the most dominant—the bullies who rule the playground—down to the most subordinate. The A-list monkeys engage in a range of highly social activities, such as grooming one another, while those with lower status are more isolated and likely to be picked on.

Being a subordinate monkey, the researchers found, is stressful. That daily drag results in higher baseline levels of the hormone cortisol—strongly associated with anxiety and fear—and a less active dopamine system.

Wilson and his team decided to see how the monkeys would respond to increased choices of food. While one group continued to receive only the healthy monkey chow they're typically fed, another group got an added menu item—sweeter, fattier banana pellets. Over time, the researchers found that the dominant monkeys didn't change their eating habits much, but the subordinate monkeys began gobbling far more of the banana treats.

To the researchers, it started to look a lot like they were addicted.

Wilson and his team theorize that for the low-status monkeys, the increased fat and calories in the banana pellets helped restore some balance to their brain chemistry by tamping down cortisol levels and firing up the neglected dopamine system.

"Our hypothesis is that stress shifts the balance to the reward pathway," Wilson says. "The subordinate monkeys are basically self-medicating with what you might call comfort food. It really underscores the importance of the social environment and the biological response."

Social environment is changeable—genetic code, not so much.

Rohan Palmer, an assistant professor of psychology in Emory College, is tapping into huge sets of available data to study how genetic differences may make some people more vulnerable to substance addiction than others.

By identifying and analyzing patterns in the human genome, and cross-analyzing those with environmental factors, Palmer hopes to develop a predictive algorithm for addiction. It's an arduous and exacting process. There are approximately twenty thousand genes in the human genome, and previous research indicates that a few thousand could play a role in addiction. Palmer's task is to predict self-reported drug use and disorder diagnosis among hundreds of thousands of people using evidence from neuroimaging, neurocognitive, and behavioral studies in humans and animals.

The goal is to obtain a reliable subset of genes involved in addiction.

"The purpose of the NIH grant is to build a big reference platform that will become a resource for researchers to come and do mega-analyses of substance abuse in general," Palmer says.

Another research project co-led by Rollins School of Public Health received $1.16 million in funding for the next two years, through a cooperative agreement with the National Institute on Drug Abuse and others, to pursue research on the opioid epidemic.

Hannah Cooper, an assistant professor in the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, leads the project with April Young 13PhD. Kentucky Communities and Researchers Engaging to Halt the Opioid Epidemic, or Care2Hope, is a collaboration between Rollins and the University of Kentucky that will take place in twelve rural counties that have been hit the hardest by the opioid epidemic. The goal is to develop approaches to prevent and treat the consequences of opioid injection.

"This is the first study I am aware of where there has been a concerted effort to build a university-community partnership around substance abuse in this part of Kentucky," says Cooper.

Expanding Treatment Efforts

If environment and genetics both play key roles in our vulnerability to addiction, the deck was stacked against Stacy, the Emory PhD student who became addicted to heroin.

Stacy's mother has struggled with heroin addiction; her grandfather died of liver cancer due to heavy alcohol use, her grandmother of lung cancer after years of smoking. Surrounded by people who used drugs, including her husband, Stacy was at the top of a long, slippery slope.

When she sought help, she was eventually connected with Justine Welsh, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and director of Emory Addiction Services.

"I don't think I would be clean right now if I hadn't started seeing Dr. Welsh," Stacy says. "Some weeks she is the only person holding me accountable, and she is someone I don't want to disappoint. That helps more than anything else."

Welsh was hired two years ago to expand Emory's addiction services because, she says, her colleagues recognized a growing need. The office now treats about fifty to sixty patients at any given time. About 30 percent of the patients meet the criteria for opioid use disorder. The majority are students under twenty-five, but the office treats adults as well. Welsh hopes to grow the office as quickly as possible—no easy task.

"Addiction can be difficult to treat, and there is commonly a stigma attached," Welsh says. "It's compounded by the fact that there is a shortage of addiction providers in Georgia, creating more barriers to much-needed care. But there are effective treatments that we are striving to make readily available. We hope that people recognize how deeply this crisis is affecting the Emory community."

Email the Editor