Raise Your Hand ... If You've Read Finnegan's Wake

When studying Joyce, it helps to take a philosophical approach

“Joyce found the reviews few and disappointing,” writes Donald Phillip Verene about the cool reception of Finnegans Wake in 1939.

Verene—Charles Howard Candler Professor of Metaphysics and Moral Philosophy in Emory’s Department of Philosophy and director of the Institute for Vico Studies—notes that the author spent a third of his life, even as he battled failing eyesight, producing the final installment of his trilogy, which included A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses. Poet Ezra Pound had been an early supporter of Joyce, but neither he nor the author’s brother was impressed by the novel. And they weren’t alone, with responses ranging between puzzled and chilly.

Verene’s first calling is as a philosopher, but through his study of Giambattista Vico (1668–1744), on whom Joyce drew heavily, Verene became a skilled reader of the Irish author. Several decades ago, Verene enjoyed the company of fellow faculty member Richard Ellmann—the Joyce biographer and first Robert W. Woodruff professor (1980–1987), for whom the university’s Ellmann Lectures in Modern Literature were named.

In the preface to his recent book James Joyce and the Philosophers at Finnegans Wake(Northwestern University Press, 2016), Verene recounts being at a conference about Ulysses in 1985. At one session, the audience was asked who had read the Wake. Verene, in the first row, raised his hand. An eerie silence descended on the room, and when Verene turned around, he discovered that—astonishingly—his was the only hand raised.

Verene discussed the incident with Ellmann, who concluded that no one dared jeopardize his or her professional reputation. As Rivka Galchen wrote in the New York Times in 2014, “Occasionally we come across people claiming to have read all of Finnegans Wake, but one hears them as if listening to a rashy traveler returned feverish from distant jungles, telling of a city built entirely of gold.” For Verene, it’s different.

“As generally an outsider and a literary amateur, whatever I said or did was of no matter,” he says. “I found myself in a most auspicious place, and still do.”

Verene joined the exclusive club of those who have “read all of Finnegans Wake” early in his career, during a year in Florence writing about Vico, the University of Naples professor of rhetoric whose most well-known work is Scienza Nuova (The New Science). The latter was Vico’s crowning achievement, attempting to create a narrative for the origin of society that would mirror what the founders of modern science accomplished for the natural world.

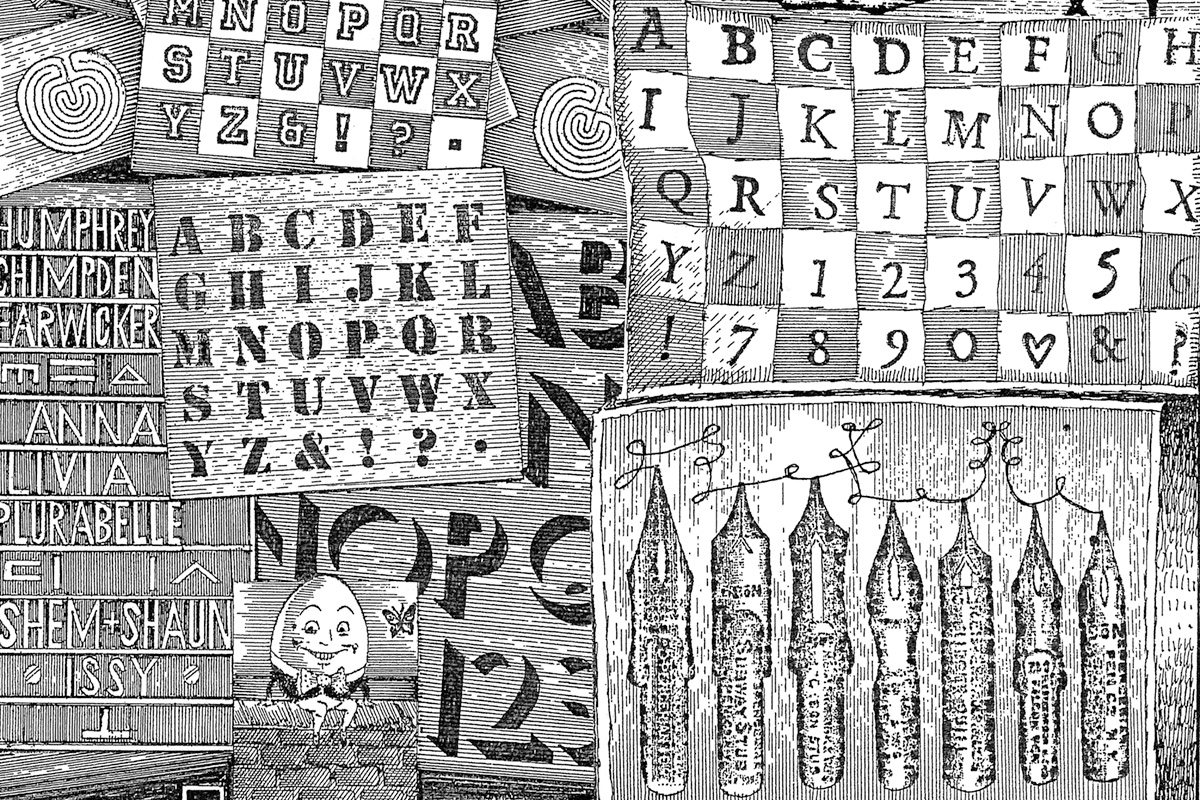

Don’t enter Joyce’s labyrinth without Vico, Verene advises. He exhorts readers to push beyond what the critical literature on Wake usually calls for—that is, knowledge of the philosopher’s cycles and his conception of etymology. Says Verene, “Joyce knew Vico well; his reader needs to, too.”

Asked why he had written the Wake as confoundingly as he did, Joyce said: “To keep the critics busy for three hundred years.” Surely, he will have his wish. Meanwhile, Verene has done his part to add to the ranks of readers.