Such Stuff As Dreams Are Made On

Rare book dealer Daniel Wechsler 90C bought a sixteenth-century dictionary on eBay. He now believes it belonged to none other than William Shakespeare.

This is the story of how two learned booksellers arrived at an audacious theory: they had acquired Shakespeare's dictionary.

After years of careful study, they presented their conclusion and the evidence behind it in Shakespeare's Beehive: An Annotated Elizabethan Dictionary Comes to Light, recently released in a revised and expanded second edition. Not surprisingly, their theory has created a stir among scholars of Shakespeare, and the ensuing drama continues to unfold

In the world of antiquarian bookselling, most dealers are specialists who have spent years developing expertise in a genre, a period, or both. Daniel Wechsler 90C is a rarer breed—a generalist who cares less about first editions than about the backstory of a book. What interests him most are the relationships between books and their readers: what books mean to people and how they use them. “Whenever there’s a personal connection between the owner and the book,” he says, “I’m interested.”

That interest has altered the course of Wechsler’s life, taking him down the unexpected path that he still travels today. It is a journey that, at times, has created anxiety about his reputation and his career, and has overshadowed other parts of his life.

“My wife is really eager for this to be over,” he says, not quite joking.

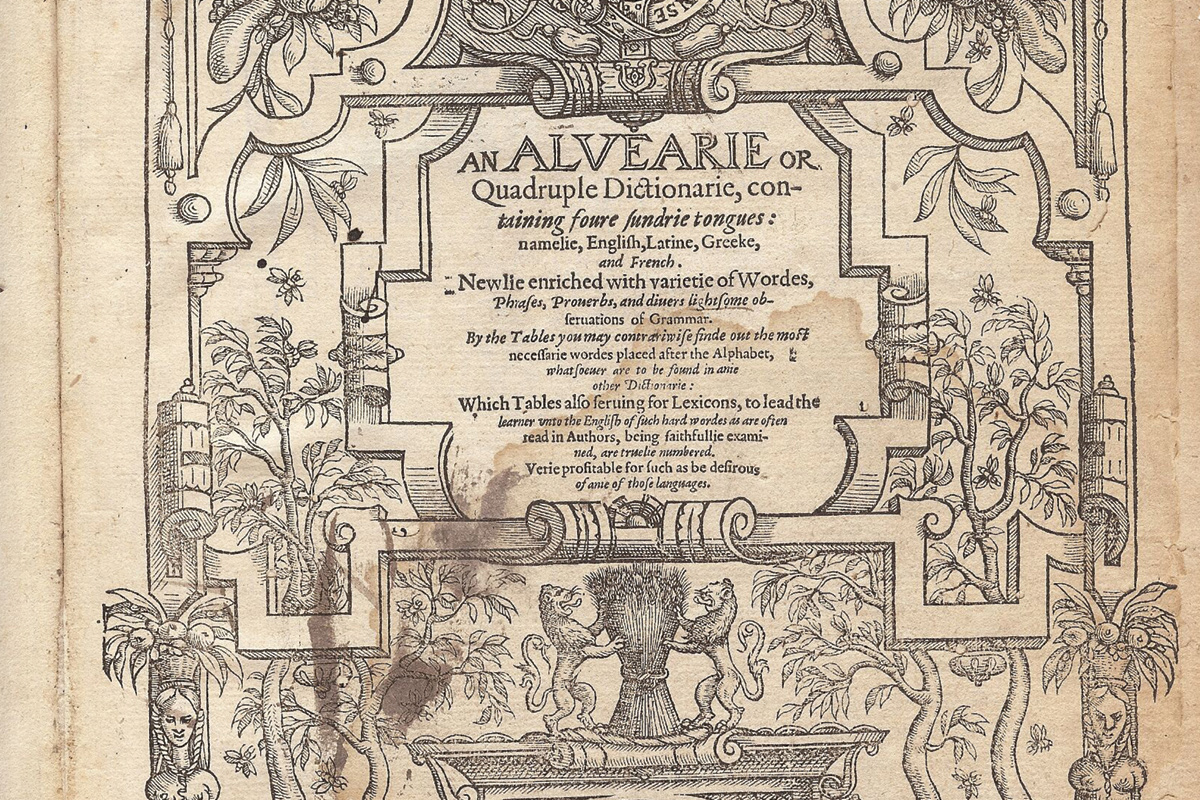

“This” began in spring 2008, when a colleague, George Koppelman, an antiquarian bookseller, came across a book on eBay he thought would be of interest to Wechsler. It was a text titled An Alvearie, or Quadruple Dictionarie, assembled by one John Baret. Published in 1580, the Alvearie (Latin for beehive) was a sixteenth-century dictionary of sorts, but, Wechsler points out, “not a dictionary in the modern sense; it’s almost more of a thesaurus, a proverbial phrase book.” The “quadruple” in its subtitle is a nod to the number of languages included in the text: English, French, Latin, and Greek.

Apart from the book’s age, Koppelman thought it would pique Wechsler’s interest for another reason: It was filled with thousands of handwritten annotations. The book hit all of Wechsler’s sweet spots as a bibliophile and book merchant. He and Koppelman decided to enter a bid together.

“The auction started at one dollar,” Wechsler recalls. Koppelman wanted to enter an initial bid of two thousand dollars. Wechsler suggested they bid higher, and the men settled on $4,300. They entered the figure, pressed the “Place Bid” button, and took a deep breath. All they could do was wait.

When the auction ended, the final sale price was $4,050. Koppelman and Wechsler were the newest in a centuries-long line of owners of Baret’s Alvearie, which, they would discover later, was one among what was probably only a thousand copies printed by the London-based publisher Henry Denham.

If it seems strange that two highly respected antiquarian book experts would be trawling eBay for texts to buy with the goal of eventually reselling them, perhaps you haven’t been on the site in a while. Bookselling is a brisk business on eBay, and there’s an entire subsection devoted exclusively to antiquarian and collectible books. On any given day, there are more than a million listings in this subsection alone. Wechsler says it’s not unusual for antiquarians to keep an eye on the site, looking out for choice finds.

“You might have better luck buying [rare books] on eBay than at Sotheby’s,” he says.

And sometimes you might get a lot more than you bargained for. When Wechsler and Koppelman came into possession of the Alvearie, which was listed by a Canadian seller, they knew they had made a worthy purchase—but they hardly imagined the narrative that they had set in motion.

“The very first thing we did was open up the box and take a look at the book, and you could tell right away that it wasn’t in the original binding anymore, but the actual text block—the pages themselves—were in pretty good condition,” Wechsler says.

With books, as with other collectibles, the more intact the original elements of the book, the better. But this big-ticket purchase was hardly a disappointment. The more the two thumbed through the pages of Baret’s Alvearie, the more unexpected elements and intriguing possibilities they discovered— particularly in the handwritten notes.

“When you find a sixteenth-century book with notes in it, it really is a lot more interesting,” Wechsler says. “Now there’s a real movement toward trying to understand as much as you can about the period, and you can often do that through studying the handwriting and the note taking, the methodology of how someone was thinking.”

As Wechsler and Koppelman studied the Alvearie text, they began to notice that the author of the many annotations had what Wechsler refers to as “poetic turns of phrase, a certain poetic quality of mind.” And then they picked up on an attribute of the notes that suggested, when considered alongside a growing pile of evidence, that the anonymous author of these marginal musings actually might have been one of the most famous literary legends of all time.

“There are two printed capital letters from the Baret, and two letters only, that the annotator, whoever he was, occasionally imitates this ornate design of—just the ‘W’ and just the ‘S,’ ” Wechsler says, “and we began to have fun with the idea that, well, you know, could it have been Shakespeare?”

The thought was dizzying. “There are no books from Shakespeare’s library that have even been authenticated,” Wechsler says, so, “if you say, ‘This is Shakespeare’s dictionary, and you discovered the book, what you’re getting at is that you’ve found the holy grail of humanism.”

For all the flights of imaginative fancy the booksellers’ minds were taking, Wechsler knew that even entertaining the question was the professional equivalent of entering a hornet’s nest, and the stings could be painful.

“If you come out and say something like this, there’s such a career risk,” he explains. “We’re reasonably respected guys. And what do you do? To suddenly announce to the world, you know, ‘Hey! I think I’ve found Shakespeare’s own dictionary, and it’s got all his notes in it!’ I mean, we knew how that was going to sound.”

Wechsler and Koppelman didn’t rush to any conclusions. “We spent several more years working on writing our study, studying Shakespeare in greater depth, and studying source books in greater depth,” he explains. The more they learned, the more Wechsler and Koppelman were convinced that their copy of Baret’s Alvearie once belonged to the bard himself.

As the booksellers grew closer to making a public case for Shakespeare as the hand that penned the annotations in their copy of the Alvearie—a case they would lay out assiduously on a meticulously designed website; in the thoroughly researched book Shakespeare’s Beehive: An Annotated Elizabethan Dictionary Comes to Light; and before local, national, and international press, including the New Yorker and the Guardian—two milestone years in Shakespearean history approached: 2014, the 450th anniversary of the bard’s birth, and 2016, the 400th anniversary of his death. Amidst such heightened public attention, it was obvious that there would be high demand for evidence to support the booksellers’ claim that Shakespeare was the author of the annotations—but would Wechsler and his colleague potentially be accused of profiteering from these anniversaries?

Ultimately, they decided, all they could do was present their case and watch reaction unfold.

“We just felt that no one else would ever feel comfortable saying it first,” Wechsler says. “From there, hopefully, there would be a conversation that would take place in a productive way.”

While there was certainly lively discussion, many scholars and experts stopped short of descrediting Shakespeare’s Beehive and its claims.

“Even the most skeptical scholar would be thrilled to find a new piece of documentary evidence about William Shakespeare,” wrote Michael Witmore, director of the Folger Shakespeare Library, in a blog post last spring. “Scholars, however, will only support the identification of Shakespeare as annotator if they feel it would be unreasonable to doubt that identification. This is a fairly high evidentiary standard, since it requires one to treat skeptically the idea that this handwriting is Shakespeare’s and to seek out counterexamples that might prove it false. . . .

“As the library of record for Shakespeare and the leading documentary source for his works, the Folger will be one of the places where Koppelman and Wechsler’s claims are evaluated by scholars. At this point, we as individual scholars feel that it is premature to join Koppelman and Wechsler in what they have described as their ‘leap of faith.'"

Wechsler anticipates that the second edition of Shakespeare’s Beehive, scheduled for release in late summer or early fall, will help spur the conversation along, as new discoveries will be revealed. The timing of the book’s second edition is also interesting in light of Wechsler’s Emory connection; the university is exhibiting Shakespeare’s First Folio this fall.

It was at Emory that Wechsler’s love of Shakespeare was ignited. After graduating with a degree in English, he tried his hand at writing, but decided he might do better selling books. After getting his start at a local bookstore, he eventually felt he had picked up enough knowledge of the trade to hang out his own shingle.

He spent the next two decades building his career and reputation. While his current project has exposed him to a certain degree of criticism, he hints that more recent developments will likely dispel some naysayers.

Wechsler admits that the Shakespeare’s Beehive project has exacted an extraordinary amount of time and commitment—not to mention sleep. “A lot of sleep,” he says.

But it has also given him a great deal. “If you’d asked me who my favorite writer was after college, I would’ve said, ‘Shakespeare.’ Overall, the Alvearie has led me to a tremendous knowledge of Shakespeare and the language of the period that I’m so grateful for,” he says. “I fully admit to sort of worshiping Shakespeare on a personal level. I think he was one of the most extraordinary human beings who ever existed.”