Depictions

of humans and monkeys, birds and snakes, jaguars

and crocodiles weave their way through the new Art of

the Ancient Americas galleries at the Michael

C. Carlos Museum, transforming one to another like

a shared hallucinatory vision. The objects reveal composite

images–a bowl with elements of a stingray and a boa

constrictor; a goblet with a human head and feline fangs–that

capture many layers of self and embody a unity of nature

and all creatures.

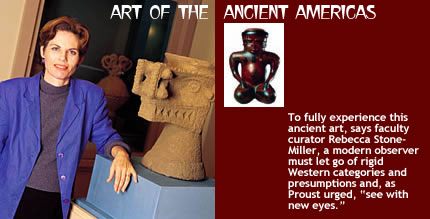

To

fully experience this ancient art, says faculty curator

Rebecca Stone-Miller, a modern observer must let go of

rigid Western categories and presumptions and, as Proust

urged, “see with new eyes.”

Clear

distinctions between humans and animals are obliterated

in the exhibit, “which displaces the human from a

central position . . . [and] reverses a Western assumption

that animals and plants lie beneath the human in the cosmic

scheme,” says Stone-Miller, associate professor of

art history.

The

Art of the Ancient Americas galleries, which opened in

September 2002 after more than a year of renovations under

the direction of architect Michael Graves, houses one

of the most important collections of such art in the Southeast

and one of the key collections of art from ancient Costa

Rica in the country.

The

exhibit displays more than five hundred of the museum’s

nearly 2,200 works from ancient Mexico, Honduras, Nicaragua,

Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Crafted

from clay, stone, metal, wood, fiber, bone, and shell,

the pieces reflect the belief systems and lifestyles of

the Maya, Aztec, Inca, and other ancient American cultures.

About

one-fourth of the objects, which include effigies, jewelry,

ritual artifacts, vessels, and textiles, have never been

displayed before.

Part

of preparing the exhibit involved identifying the animals

depicted on the objects. This often proved trickier than

it might seem, given that many animals were in dual or

transforming states. An image of a toad with ears, for

example, must have been achieved by blending in characteristics

of a human or other animal, since toads don’t have

ears.

A

person might even be combined with a plant, as evidenced

by a South American stirrup spout vessel showing a round-bodied

musician/peanut playing a flute. “The unity of person

and peanut is neither humorous nor trivial, but represents

. . . [that] the plant and the person are inexorably linked,”

says Stone-Miller. “More colloquially, ‘You

are what you eat.’ ”

A

good amount of detective work was involved in determining

the meaning or use of the pieces. For example, outlines

of a textile print on a South American female effigy tells

that the effigy was dressed, just as a real person would

have been; wear on the surface of an oval ceremonial grinding

platform from Costa Rica shows that the stone grinding

platform was actually used before burial; and yellow-brown

swabbed residue inside a watering vessel indicates that,

rather than water, maize beer was poured through the device.

Emory

scientists in related fields contributed their expertise

as well. Associate Professor of Environmental Studies

William B. Size conducted a groundbreaking geological

analysis of greenstones (“jades”) for the catalogue;

William Casarella, chair of Emory Hospital’s Radiology

Department, assisted in X-raying various ceramic pieces;

and Robert Wirtz, of the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, helped interpret a vessel depicting a survivor

of leishmaniasis–a disfiguring disease caused by

a parasite carried by animals, including rats and dogs,

and transferred to humans by the sandfly.

The

museum’s emphasis on acquiring art from the ancient

Americas began in 1988 with pieces from the collection

of Atlantans William C. and Carol W. Thibadeau.

William

Thibadeau, who died in November 2002 at eighty-two, donated

seven hundred pieces and sold the museum another six hundred

at a bargain price. Valued at $1 million in 1992 and now

worth three times that, the collection comprises an “interesting,

wide-ranging, and idiosyncratic grouping of works,”

says Stone-Miller, and was the impetus behind the museum’s

1993 expansion.

“So

many works of such quality,” says President William

M. Chace, “deserved to be seen in spacious and handsome

galleries.”–M.J.L.