|

Volume

77

Number

4

Health

for All

Fear

of Flying

Flying

II: High Anxiety

Virtual

Vietnam

Uncovering

the Past

Wired

New World

Enigma:

Physics Band

Emory

University

Association

of Emory Alumni

Current

News and Events

Emory

Report

EmoryWire

Knowledge@Emory

Sports

Updates

|

|

|

|

|

|

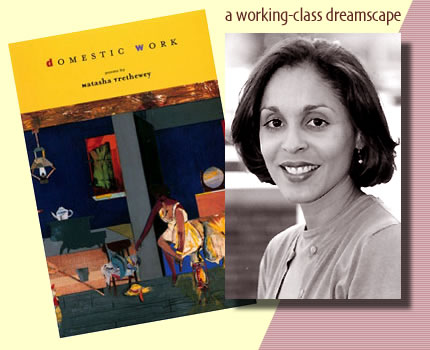

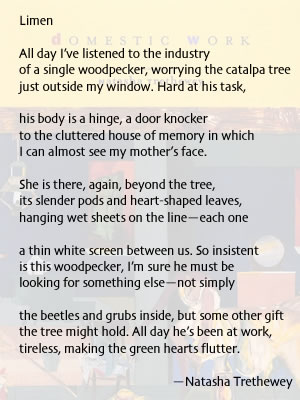

In

her poems, Natasha Trethewey captures ancestral memory

like vintage photographs kept in a shoebox beneath her bed,

pulled out and examined one by one. She reads into lined faces

and distracted gazes all the hopes and desires extinguished

by incessant labor; dreams too large to contain but too risky

to say aloud.

“I

figured out that I had a whole collection of poems that try

to explore the everyday work that we do,” Trethewey

says of the poems collected in Domestic Work,

which won the Cave Canem poetry prize, a Mississippi Institute

of Arts and Letters Book Prize, and the 2001 Lillian

Smith Award for Poetry. “Not just the work of earning

a living and managing households, but also the work of self-discovery,

relationships, the people we live with or without, and of memory

and forgetting.”

Trethewey,

who joined the creative

writing faculty at Emory this fall, has written poetry since

she was a child growing up with her African-American mother

and stepfather in Decatur, summering at her African-American

grandmother’s home in Gulfport, Mississippi, and visiting

her white father in New Orleans.

Sensory

traces of each locale and culture simmer in her words–heavy

blossoms in afternoon rain, the Delta heat, gumbo and red beans.

Poet

Rita Dove, who wrote the introduction to Domestic Work,

says Trethewey’s sonnets, traditional ballads, and free

verses “shot through with the syncopated attitude of blues”

create a “tapestry of ancestors . . . lives pursued on

the margins, lived out under oppression and in scripted oblivion,

with fear and a tremulous hope. There’s the work-at-home

seamstress who wears a wig every day just in case someone drops

by . . . the father turned amateur boxer who has learned to

survive by ‘holding his body up to pain.’ ”

In

a recent class, Trethewey guided a circle of undergraduates

through each other’s poems, stanza by stanza, searching

for text and subtext. “What is the undercurrent of meaning?”

she asks. “What were you getting at in that image?”

Although

Trethewey is now a critically acclaimed poet whose work has

appeared in the American Poetry Review, the New England

Review, the African American Review, and the Best

American Poetry 2000, she remembers all too well the determined,

sometimes painful, journey she made to claim her craft.

Trethewey’s

first book of poetry was placed in the library of Venetian Hills

Elementary School in Atlanta. “It was filled with trite

little rhymes about historical figures like George Washington

and Martin Luther King Jr.,” Trethewey recalls, grinning.

“My third-grade teacher bound it and the librarian went

along with her and placed it on the shelves.”

She

kept writing, becoming editor of the Redan High School newspaper,

then turning to fiction and short stories. “My mother died

when I was a freshman in college, and to try to grapple with

that huge loss, I turned to poetry, to try to make sense of

the world and me in it,” she says. She

kept writing, becoming editor of the Redan High School newspaper,

then turning to fiction and short stories. “My mother died

when I was a freshman in college, and to try to grapple with

that huge loss, I turned to poetry, to try to make sense of

the world and me in it,” she says.

And,

in a process that allows her to identify with struggling poets

everywhere, her early results were less than stellar. “I

actually wrote a poem that had a line in it about sinking into

an ocean of despair, with the word ‘sinking’ going

diagonally down the page,” she says, shaking her head.

“My father and stepmother are both poets and they absolutely

ripped that poem to shreds. I ran upstairs sobbing, vowing never

to write another poem.”

Trethewey

says now she appreciates their honesty. “My father wasn’t

going to say nice things to me to spare my feelings, because

he took seriously my potential,” says Trethewey, who dedicated

Domestic Work to him. “Now it goes both ways–he

sends me his work to critique.”–M.J.L.

|

|

|

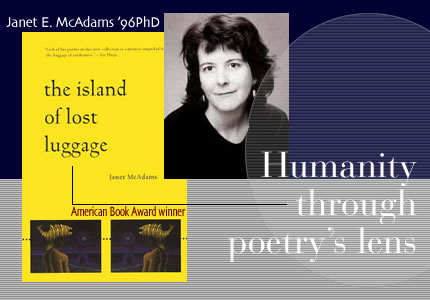

There

is no winter here of heart . . .

The

opening sentence of the poem “Cemetery Autumn,”

one of those featured in the award-winning collection, The

Island of Lost Luggage, by Janet

E. McAdams ’96PhD, gets at the core of McAdams’s

work: while some of her themes are chilling, her poems also

are infused with a human warmth and reason that lend balance

to even the darkest among them.

“The

poems are about loss and recovery, compassion and despair, complicity

and resistance,” McAdams said in an interview in late September.

“I want to remind readers–and myself, continually–of

the world’s miraculous beauty. But I also want to map out

a kind of responsibility not to turn away from its ugliness.

I think the greatest poetry is there to both comfort and disturb.

I know in the past few weeks, I’ve found poetry to be of

great consolation.”

McAdams’s

collection won a 2001 American Book Award and the 1999 First

Book Award in Poetry from the Native Writers’ Circle of

the Americas/Wordcraft Circle. Noted for drawing meaningful

connections between the personal and the political, McAdams’

poetry gives equally careful consideration to conflict in Central

America, the destruction of the environment, and the twisted

machinations of love and loss. The title poem, dedicated to

a hometown friend who died in the 1983 Korean Airlines crash,

grapples with the mysteries of mortality and passage. Rich in

concrete details that lighten their touch, many of her poems

have a decidedly activist bent.

While

earning her Ph.D. in comparative literature at Emory, McAdams,

who is of Scottish, Irish, and Creek Indian descent, helped

found the Native American History Month program at the University.

Her poetry has earned her fellowships from both the Georgia

and Alabama state art councils. She is now the Robert H. Hubbard

Professor of Poetry at Kenyon College. —P.P.P.

|

|

Also

in Précis:

Crawford

Long Hospital undergoes $270 million renovation

Doc

Hollywood: The Musical

A

Journey of Reconciliation

Depression

and high blood pressure make deadly combination

Growing

Green: The Piedmont Project

Library

augments literary holdings

A

Race of Singers

Remembering

Evangeline T. Papageorge ’29M

Emory’s

“hidden history” revealed in Oxford Historical Cemetery

Faith

Journey: Daniel B. Cole ’93C

|

|