“Can

I get a reading?” The voice of therapist Page Anderson

breaks into my headset.

“So

far, I'd rate the highest point about seventy-five,”

I say, almost proudly. I am rating my anxiety level on

a scale of one to a hundred. This was my fourth takeoff

in half an hour and my best one yet.

My

grandmother used to travel all over the country by Greyhound

bus because she was terrified to fly. Apparently fear

can be handed down through generations, like red hair

or a stubborn streak. About a year ago, after a particularly

rough flight, my own air travel anxiety skyrocketed to

a level that became problematic: I started to find excuses

not to take long trips, put off making vacation plans,

seriously considered driving from Atlanta to San Francisco

for a two-day conference.

Last

spring, as it began to dawn on me that this little personality

quirk was severely curtailing my travel options, I heard

about an Emory psychology professor doing cutting-edge

work with fearful fliers. I thought I might have a shot

at bringing my ballooning paranoia under control.

So

I completed an eight-week course in virtual reality therapy,

a program that delivers a tried-and-true method for curing

phobias–exposure–in a radical new way: computer

simulation.

The

first few sessions with Dr. Anderson followed a pattern

of traditional, one-on-one therapy. We discussed my fear

and its possible sources, helping me explore and assess

the trouble. I then began to learn myriad anxiety-management

techniques, including breathing practices, relaxation

exercises, and mental gymnastics to help me stop the vicious

cycle of fearful thoughts (“this plane is going to

burst into flames and hurtle to the ground,” for

instance) when they threatened to spiral out of control.

I

also learned some convincing statistics about airline

safety, which proved an effective offense against my particular

brand of fear:

•

If you flew every day of your life, probability indicates

that it would be twenty-six thousand years before you

were in a fatal accident.

•

Flying is ten times safer than traveling by train.

•

A sold-out 747 jet would have to crash every day, with

no survivors, to equal the highway deaths per year in

this country.

•

You are nineteen times safer in a plane than in a car.

I

compiled these into a “cheat sheet” with Dr.

Anderson’s instructions to carry it with me on air

flights and review this litany of comforts during panicky

moments.

When

I had stockpiled an arsenal of anxiety defenses, it was

time for the exposure portion of the program. Rather than

driving to the airport as phobic fliers in standard therapy

would have done, I walked into the next room, stepped

up onto a platform where an airplane-like seat was perched,

and strapped on a weighty piece of equipment called a

head-mounted display.

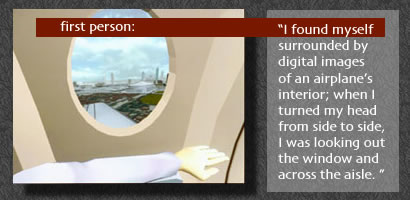

I

found myself surrounded by digital images of an airplane’s

interior; when I turned my head from side to side, I was

looking out the window and across the aisle. Airplane

sounds were piped into the headset’s earphones. The

contraption took some getting used to, but it did the

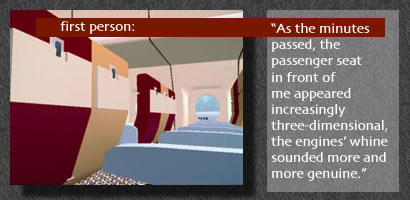

trick: as the minutes passed, the passenger seat in front

of me appeared increasingly three-dimensional, the engines’

whine sounded more and more genuine, and the window view

became nerve-wrackingly authentic. By takeoff time, with

the help of Dr. Anderson’s verbal scene-setting and

a certain amount of conscious vulnerability on my part,

I could practically smell the jet fuel.

What

followed was a series of virtual flights, with special

emphasis on takeoff and turbulence (particular trouble

spots for me). Dr. Anderson even created virtual storms,

in which the platform below me shook, thunder boomed inside

the headset, and lightning flashed outside the digital

plane window. Speaking into the headphones, she checked

in with me at key points, measuring my anxiety and offering

helpful suggestions.

Sure

enough, as I grew more comfortable with the sensations

of air travel, the fear began to fade. After four sessions

of intense virtual reality therapy, I was beginning to

feel more hopeful about flying. I won’t say I was

eager to, say, hop a flight to Australia, but when I was

obliged to attend a family wedding in Memphis, I didn’t

insist on taking a Greyhound bus. Instead I managed to

book a reservation, board a plane, and fly, clutching

my cheat sheet (“you are twice as likely to be killed

by a bee sting than an airline accident”) and trying

to think of the ocean. It wasn’t easy, but I did

it. And making the trip gave me hope that I might someday

be like most people I knew–those baffling fortunates

who casually accept air travel as a simple fact, an everyday

convenience, a given.

My

budding confidence was shattered on September 11, as I

watched hijacked airplanes explode into the twin towers

of New York City’s World Trade Center, again and

again.

The

statistics on air travel hold as true today as they did

a year ago: The average person’s chances of being

in a fatal airline crash are about one in ten million.

Even lower are the odds of falling victim to a horrific

act of terror.

But

statistics are cold comfort in the face of senseless destruction.

Those damaging images and their profoundly tragic meaning

have become imbedded in the collective American consciousness,

and the resulting fear defies logic. It seems I am not

the only one whose fragile trust in air travel safety

and security was deeply shaken by the terrorist hijackings.

Judging from the sharp decline in ticket sales since the

September attacks, thousands of Americans who once took

flying for granted have reevaluated their casual confidence.

These

days, when I make excuses about not flying, people no

longer look at me oddly, with that old mixture of puzzlement

and pity. Instead, they nod their heads understandingly.

They get it. Whereas I once felt like an outcast of sorts,

I now have ample company. I am no longer alone with my

fear of flying.

I

wish I were, though. Oh, how I wish I were.