IT

IS THE MORNING FOLLOWING THE MIDNIGHT BONFIRES THAT

launch

the

festival of Holi in cities and villages throughout India,

and

people

have only begun to celebrate. We are in Banaras, one of the

oldest

and most sacred of Indian cities. It is the city of the deity

Shiva,

considered

by many Hindus to be the origin, center, and final end of

the

universe. Thousands come to Banaras to die each year to achieve

spiritual

liberation from the continuing cycle of rebirth, and more

than

a million pilgrims—Hindu, Moslem, Buddhist, and Jain—visit

the

myriad

temples, shrines, and holy teachers of this city and bathe

along

a three-mile length of steps (known as ghats) that lead

into the

sacred

Ganges river.

It

is difficult to recognize such sanctity amidst all the revelry

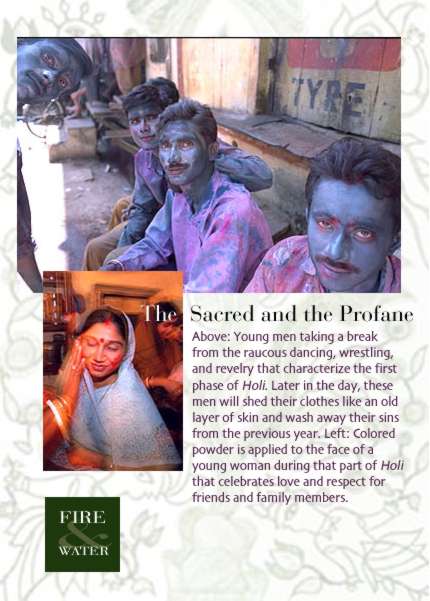

on this particular day. The storefronts are boarded up. Roving

bands of drunken young men have taken over the neighborhoods–dancing,

wrestling, and shouting insults at one another. Women and children

have retreated to the safety of their homes to watch the spectacle

from balconies and rooftops and to throw colored water on the

crowds below. The only semblance of order in the neighborhood,

a lone policeman, is so intoxicated he can hardly walk. It would

seem as if this holy city has been turned upside down.

Indeed,

it has.

Holi

is a popular Hindu festival that occurs each year on the full

moon concluding the lunar month of phalgun, usually corresponding

to March of the Gregorian calendar. Its origins are most likely

prehistoric, a rite of spring celebrating fertility and a new

harvest. While this festival embodies many different legends,

the dominant folklore in Banaras concerns an evil female rakasha

(demon) named Holika, who conspires with the King to have a

pious young prince killed for his belief in Krishna. Taking

a secret potion to protect herself, she jumps into a bonfire

with the young boy. Yet because of the strength of his faith,

the prince emerges unscathed while the evil Holika is consumed

by the flames. Symbolic bonfires begin the first phase of Holi

at midnight, when they are ignited in neighborhoods throughout

Banaras. Young men gather to revel and dance around these bonfires,

which can rise as high as thirty feet. Families visit the pyres

as well, performing a ritual prayer known as puja and circumambulating

the flames to purify themselves of sins from the previous year.

This

rite of purification is also a significant rite of reversal

in which society briefly turns its rules upside down; during

the second phase of Holi, many social taboos are temporarily

suspended. The idea is to bring the year’s dirt and sin

out into the open so it can be washed away. Hence, the debauchery.

This presents a special opportunity for people at the bottom

of India’s social hierarchy to unleash their frustrations

and tell the upper classes exactly what they think of them with

(relative) impunity.Because

the rules of social hierarchy are particularly restrictive in

Banaras, it is not surprising that the second phase of Holi

would be all the more rowdy in this city. It is also more colorful,

as women and children squirt each other and passersby with pichkaris,

long syringes filled with colored water, and bystanders and

celebrants alike are pelted with water balloons, buckets of

dyed water, and occasional cow dung patties throughout the morning.

There

is little if any official regulation of these activities; nothing

prevents this festival from escalating into a full-scale riot

save the unwritten rules of the culture itself. Yet it would

seem that culture alone is adequate, for by noon the streets

of Banaras grow quiet. The men return to their homes, discard

their old clothes like an outer layer of skin, and literally

wash away their sins. They don new white kurta pajamas and return

to the streets with their families, hugging each other affectionately

and gently applying a colored powder to the cheeks of friends,

neighbors, and loved ones. Students pay their respects to their

teachers; children to their parents. Most Hindu families host

visitors well into the night and serve traditional pastries

called gujiya. The time-honored order is restored and reaffirmed.

Such

is the nature of this rite of reversal, which not only acts

as a kind of cultural pressure valve but also reestablishes

the cultural norm by way of its exceptions. Such rites are not

unique to Holi; similar examples can be found in Mardi

Gras and the Carnival of the Americas, large-scale festivities

of uninhibited excess just prior to the austerities observed

by Catholics during Lent. In recent years, the antinomian edge

of these American celebrations has been blunted as they have

entered the mainstream of popular culture. This also is occurring

among practitioners of Holi as India becomes increasingly

westernized under the influence of the global marketplace. Yet

many places in India continue to celebrate Holi in the

more traditional way. Banaras is one such case, a city torn

between the competing forces of old and new in post-independence

India. It is therefore both ironic and appropriate that one

of India’s holiest places is also one of its Holi-est

places.

Ron

Barrett is completing his Ph.D. dissertation on stigma among

leprosy patients in Banaras. Victor Balaban’s work has

appeared in Life and Emory

Magazine. Barrett and Balaban documented the celebration

of Holi in part with funding from the Emory Program in

Asian Studies. These photographs will be part of an exhibition

in the Schatten Gallery of the Woodruff Library, August 20—October

15, 2001.

|