|

| ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

|

Volume

75 The Once and Future Mummy Museum

The blue represents the vast unknown, the source of inspiration, like sky or sea, and the milk is the nourishing product of that inspiration.

|

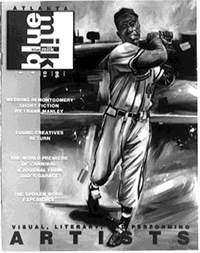

Got bluemilk? Emory alumni and students are at the heart of a publication that is both observing and transforming the arts community in Atlanta By Andrew W.M. Beierle

GOT BLUEMILK?" It’s a question heard with increasing frequency in bookstores, restaurants, and galleries around Atlanta as more and more of the city’s writers, artists, actors, and musicians become familiar with the funky, free magazine that chronicles the burgeoning local art scene. In the parlance of booksellers, bluemilk has legs—it is so much in demand that it seems to walk out the door on its own, leaving distributors with more month than they have magazines. That’s one of the reasons bluemilk’s publishers increased its frequency from bimonthly to monthly after just three issues and pumped up circulation to fifteen thousand. Another is that submissions of art, both literary and visual, have gone through the roof.At the heart of this phenomenon is an "Emory mafia" that includes Chris Hansen ’99C, Richard Hermes ’98C, and Ben Tran ’98C, who joined editor-in-chief Chris Kowalski (a Tulane alumnus) in his vision quest in late 1997. Other Emory students and alumni such as Brett Lockwood ’90L, the magazine’s legal advisor, frequently contribute to bluemilk, and the work of some of the best-known writers on the Emory faculty, among them Lucas Carpenter, Ha Jin, Frank Manley, and John Stone, has graced its pages. "Emory has been extremely nurturing and supportive throughout this entire process," Hermes says. "It has been our sounding board in a way. It has spurred a lot of momentum. [Poet and novelist] Tony Grooms submitted a piece of fiction for our February issue because he had seen Ha Jin’s piece, so that has helped a lot. But at the same time I think one of the interesting things we’re doing is that we have really stepped out of Emory and into the city, into Atlanta, and really made a commitment to making our own way." The origins of bluemilk are modest. Kowalski and Tran pulled together the first couple of issues in Kowalski’s one-bedroom apartment on Rock Springs Road in Atlanta’s Morningside neighborhood. It was Tran who enlisted the participation of Hermes, whom he first encountered at Emory’s Yeats summer school in Ireland, and Hansen, whom he met at a study abroad program at Oxford University. Like a kid recruiting friends to help him build a fort, Tran approached Hermes and Hansen with an inexpensive, low-resolution laser printout of some art and poems and asked if they were interested in launching a new magazine. "It was just an idea. It was wild and seemed fairly implausible at the time, but I said, ‘Sure,’ " Hansen recalls. More than a year later, Hansen, Hermes, and Kowalski continue to publish bluemilk (Tran is on a Fulbright fellowship in Vietnam), succeeding despite significant odds in the often mercurial world of publishing startups. Fueled by midnight coffee from the nearby BP station, twentysomething self-confidence, and a surfeit of heart, they have carved out a niche for themselves in the Atlanta arts community and recently took on responsibility for a second, theater-related publication. "Artistically, there is a lot going on in Atlanta," Hermes says. "We have the kind of people on our staff who continually want to push themselves and discover something new on a daily basis. Through the magazine, we can share that with everybody else. . . . "I’m very proud of what we have been able to accomplish. Just operating for a year and not being in the red is a huge accomplishment. But the thing is, we’re so naive, we don’t even know that. People have to tell us that."

Late last summer, the bluemilk operation moved into an unprepossessing storefront on a commercial-industrial stretch of Spring Street parallel to Interstate 75/85. The continuous susurration of traffic on the downtown connector provides a soothing aural counterpoint to the visual cacophony inside the cluttered workspace.

The ambiance is definitely more spit than polish, a confusion of second-hand furnishings and office equipment. The walls are hung with the works of local artists, some raw, such as Kowalski’s huge, cartoon-like black cat, made menacing by its size and wild brushstrokes; some gemlike, including a jolly blue-green Buddha and an impressionistic rendering of fireworks over Cinderella’s castle at Walt Disney World that might well have been titled "Monet at the Magic Kingdom," the work of Chinese immigrant Wen Ze Chen. On a morning in late January, Hermes and Hansen, who serve respectively as managing editor and executive editor, are seated on a faded green crushed-velvet sofa, which frequently doubles as a bed for exhausted bluemilk staffers after a long night on deadline. They are attempting to explain their publication’s enigmatic name, which is not a reference to the slang term for skim milk but rather a sentimental homage to a high school band formed by bluemilk founder Kowalski. "The blue represents the vast unknown, the source of inspiration, like sky or sea," Hermes says. "And the milk is the nourishing product of that inspiration. . . . We’re interested in the creative process and in the fruits of that process." In an article in the December 1998 issue, Hansen wrote about the creative energy he had observed among a number of Southern artists, but the words could just as easily apply to the bluemilk staffers themselves. Call it whatever you want: inspiration, creativity, sheer will. But somehow the artist gives rise to a controlled eruption of emotions and ideas that rushes delightfully into the world. Their work is a gesture of passionate necessity. "From the beginning," Hermes says, "we saw Atlanta as a city of a lot of different pockets, different communities doing their own things artistically and culturally. There are thousands of people you don’t see, you don’t hear about, but they are creating wonderful stuff in the privacy of their studios. They might be shy, they might not be good at promoting themselves, but their work is amazing. Atlanta has a wealth of individual artistic treasures like that. . . . What we wanted to do was to provide a new forum where all sorts of artists and creative people come together and showcase their work."

In its philosophy, bluemilk is as much blue collar as blue blood; it is aimed with equal fervor at the habitués of tony Buckhead galleries and the denizens of Little Five Points tattoo parlors. Guided by the motto "Unity in Creativity," the staff encourages submissions and involvement from all quarters and embraces the work of minority artists and writers. Periodically, a special section, "Young Creatives," is set aside for the work of elementary and secondary students. "From the beginning, what we have tried to do is bring this poetry and art to everybody," Hermes says. "That’s why we put it everywhere, from the High Museum to Eats and Tortillas to little coffee shops and restaurants, art galleries and theaters. Hopefully, that will continue to be feasible, because that’s a unique thing for a magazine to do. Most magazines have very selective readerships." Part of bluemilk’s success stems from the fact that, in practice, the magazine and its staff are very much a part of the Atlanta community, both the larger artistic world and its own backyard, as evidenced by an anecdote Hansen tells about the all-night BP gas station at Fourteenth and Spring streets, just blocks from the bluemilk office. "We go down there to get coffee, food, Vivarin—whatever we need. And there is a great man who works there; his name is Willie Jackson. And we would strike up conversations with him. Well, it turns out that Mr. Jackson works with kids in inner city schools, and he wants desperately to establish a creative program for the kids, a way for them to express themselves through art. So we talked, and now he is on staff. That’s just how things happen. A lot of the people we come in contact with just find themselves on the staff pages eventually." In fact, the staff frequently exhorts readers to become contributors. In the September 1998 issue, Kowalski related a story of how his grandfather enabled him to become an artist by praising his early work. In much the same way that my grandfather encouraged me, bluemilk is attempting to encourage people that they too are creative. We take submissions from anyone who is proud of their creative work. . . . We place the established next to the unknowns. . . . Because inside we are all artists. As a result, a wave of submissions follows the appearance of each issue of bluemilk. "We get people who say, ‘I’ve been writing poetry my whole life. I’m forty-five, and this is the first time I have ever shown it to anybody.’ That’s the best part—opening those submissions," says Hermes, who shares responsibility for sorting through the over-the-transom literary queries with Hansen. "The mailman is our friend. It’s like Christmas every day." But bluemilk is not all blue skies. In contrast to its lofty aspirations and aesthetic egalitarianism, the reality is that it is a business, and none of the principals are quitting their day jobs yet. (Or night jobs. Hermes and Kowalski wait tables at Ruth’s Chris Steak House, as did Tran until he left for Vietnam. Hansen is a full-time English and philosophy major at Emory.) "We didn’t start it as a business venture," Hermes says. "We’re all artists first, and people can see that. We started it as something we could do as writers and painters. But poets and writers and painters—they usually don’t have any business sense." "The difference between working on a publication at Emory and this is that, even though I know the budget for all the student publications is too slim, at least it’s a continual flow of money," Hansen says. "This is a little bit different, because instead of having an allocated budget we are actually working with advertisers. We may be putting together the contents of an issue, but all of the editors have to drop everything and go out and try and sell ads just to pay for the issue. "I think it is an experience that almost has to happen outside the academic environment. The safety nets that have been there for us traditionally are missing, and here you are, it’s the real world. If you’re in debt, there’s not going to be somebody to bail you out at the end of the month," he says. "At times, things were pretty tough—paying the bills, paying the rent, getting the magazine out, just living our lives. What really kept all of us going has been the fact that so many people have supported us. From the outset, we have met with nothing but overwhelming enthusiasm, support, and energy from everyone in Atlanta."

What does the future hold for alumnus Hermes and for Hansen, who will graduate from Emory College in May? "I could be here for five more years, or I could be here for five months or five weeks," says Hermes, who is considering pursuing a master of fine arts degree in creative writing. "In any case, I’ve gotten a lot out of what we’ve been doing, and I feel that no matter what happens in the future, it has been completely worth it. I really believe that. It’s great to have something tangible in your hands, to be able to say, ‘This is what I have done, this is what my effort has gone into. . . . ’ To be able to make it on our own and do this has been very gratifying, and whatever the future holds, I’m not that worried about it." Hansen’s ultimate goal is a doctorate in English and, eventually, a teaching position. "But I also know that it’s going to be at least a year before I pursue that, so I will probably be here publishing the magazine for another year, and then I’ll kind of assess things. But I agree with Richard. If it just suddenly ended today, it definitely has been worth it."

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||