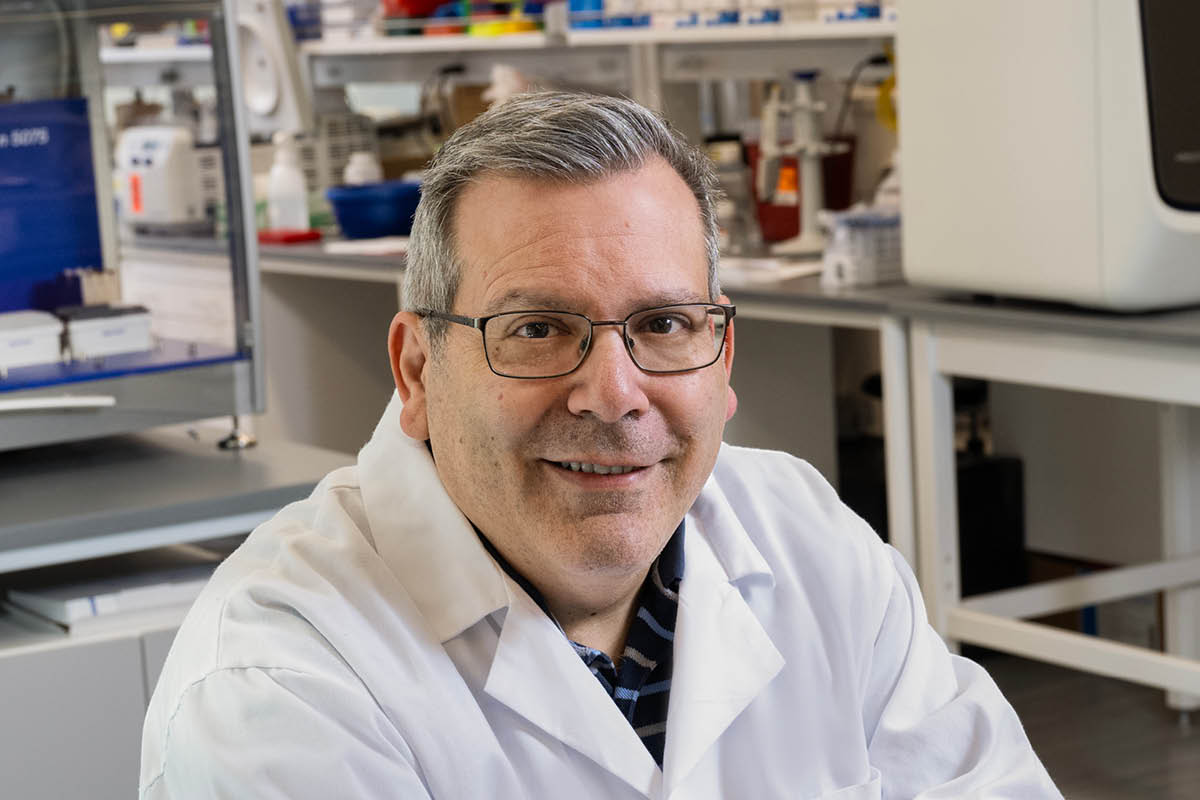

Finding the Art and Humanity in Science

I was always a reader, one of those insatiable ones — I read everything. I practically grew up at my local library, devouring books of all types, fiction and nonfiction, to feed my innate curiosity about the wider world. I remember I was in the sixth grade when the librarian actually told me, “Ravi, this author you are reading is dead — she doesn’t have any more books. It’s time for you to move on to the next genre.”

As varied as my interests were, I grew up in a middle-class Indian home at a time where I understood clearly that there were only three viable career paths if one didn’t have great family wealth: I could be a doctor, an accountant or an engineer. I was reasonably talented in math, so I chose engineering. But all through college, I couldn’t ignore the influence of humanistic studies. I was drawn to stories and books where the protagonist explored meaning, purpose and complexity, and wondered about what it meant to be human.

This wonder was magnified when I discovered biomedical science. If entropy was such a powerful force, how does one explain life — a living cell or an animal — at least temporarily pausing the drive to disorder? Science was my way of being curious. Its methods organized my thoughts, gave me structure and logic to probe the hard questions. My own research group studies brain cancer in adults and children, which has only heightened my awareness of mortality, the preciousness of time, of the present. And I ask myself: How am I spending my most precious resource, my time on this wonderful Earth? What causes, what people, what places are in my life, and how can I be a good steward of the incredible opportunity to be alive?

I truly believe that science, engineering, the social sciences, the humanities and the arts all express the same yearning we humans have to explore, to understand, to examine carefully and critically, to test, break apart and build again. We are creative, and in this process we grow as individuals and as a society. Perhaps no one in history better embodies this connection between art and science than Leonardo da Vinci. His inventions, his paintings, his wonderful and detailed sketches of human anatomy — they are at once perfect expressions of artistry, critical thinking and sound scientific theory.

As an immigrant I’ve wondered, if I had grown up in the U.S., would I still have studied engineering? There’s no way to know, but I am sure a liberal arts education would have played a larger role in my college life. As an engineer, I’ve seen the miracles science and technology enable, but I’ve come to believe that the deepest, most meaningful questions arise from our innate humanity.

Why are we here? Are we alone in this universe? Those precious moments of true joy — what are their ingredients and how can we gather more of such moments intentionally? How can we organize ourselves so art and music and the meaningful activities that “speak” to us become a bigger part of our lives? How can we become better stewards of our time on Earth and leave this planet in a better place for our children and grandchildren? More practically, can we cure cancer and other diseases? Can we create value and start new companies that power our economy equitably? Can we end wars and forge peace?

These are just some of the issues I hope Emory continues to take on with vigor and urgency. This is the motivation for us to invest in Arts and Humanistic Inquiry. And through this work, I hope Emory will help point the way toward answers to life’s biggest questions. It is important work and I believe all of us will be better off for it.

Ravi V. Bellamkonda is provost and executive vice president for academic affairs at Emory University.