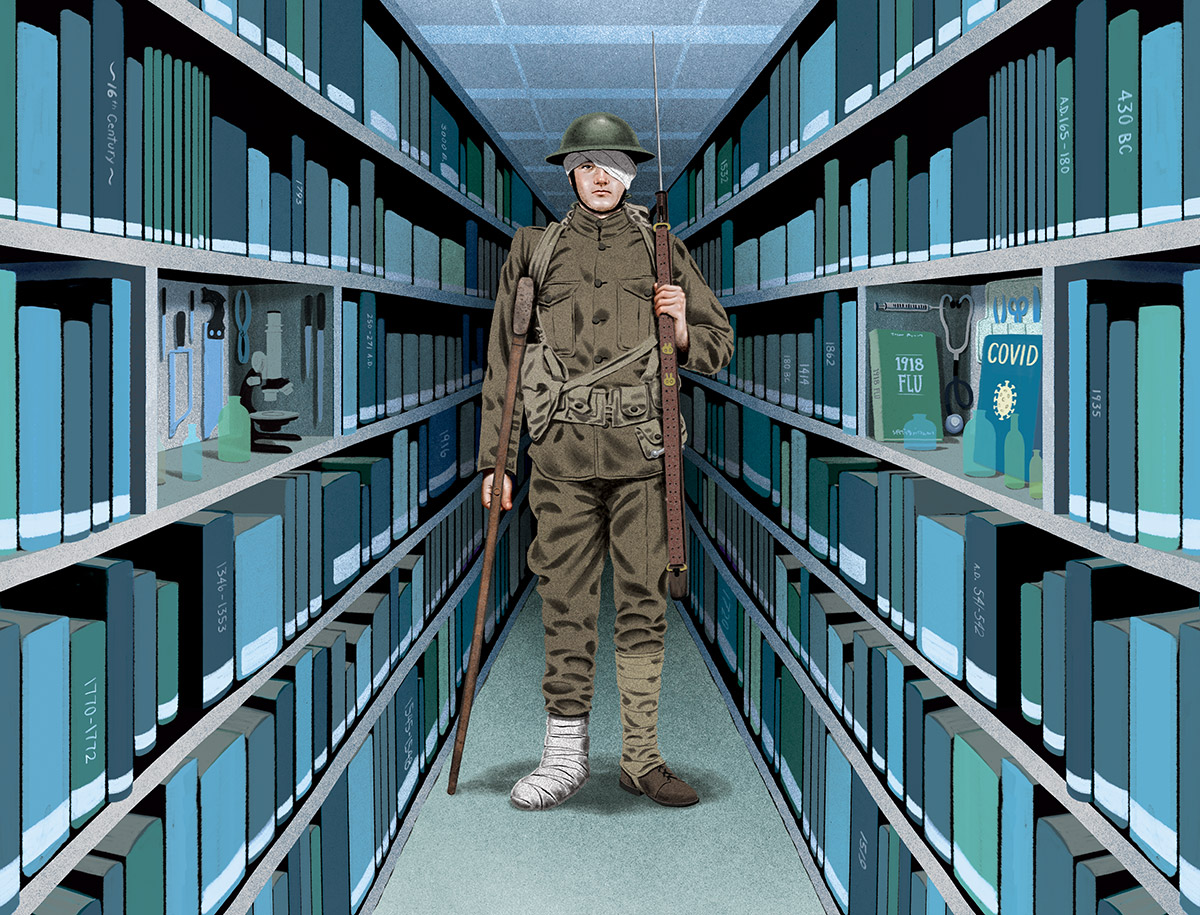

Chronicling the Human Condition

I remember the exciting moment years ago when I found it at the National Library of Medicine (NLM), the world’s largest biomedical library: a rare international report on soldiers of the allied nations who had been disabled in the First World War. I had been looking for it for years, hoping a copy had survived to help me complete my research on the persistence of wartime dialogue into the postwar era about the health and employment of the surviving the “generation of 1914.”

During this research, I had no idea that one day I would be working at the library, leading the outstanding, multidisciplinary team of its History of Medicine Division. I help steward one of the world’s largest and finest collections of historical material related to human health and disease, dating from antiquity to the present and originating from virtually every part of the world.

Like that moment in my research years ago, the work I do today with my colleagues is exciting, fulfilling, and deeply meaningful—both professionally and personally. Together, we are constantly learning more about the library’s historical collections. We are curating them to surface their stories to inform research, education, and learning. We are methodically digitizing them—not merely to make the trillions of bytes of data produced, delivered, and interpreted by the library every day more accessible to viewers, but more fundamentally to enable them to see the uniqueness of the original objects they represent with all of their exactitude. Our stewardship is a fundamental part of the main role of the library: to document, preserve, and advance understanding of the human condition.

We are constantly growing the library’s collections, retrospectively to include materials of past centuries that were born physical, and prospectively to include born-digital publications, social media, and data—all of which will become tomorrow’s historical collections.

The latest chapter of our work along these lines involves collecting and preserving selected digital and analog materials that document the coronavirus disease (COVID19) pandemic. When future researchers seek to understand early twenty-first century pandemics, they will turn to this collection—among many others held by archives and libraries across the globe—and appreciate the talented archivists, historians, and librarians who collected and preserved it for the benefit of future generations.

These successors will seek to navigate their own pandemics, learning from the past along their way. In this way, our work today fits in a continuum of medical knowledge existing in varied physical and digital forms—as it extends from the distant past to the present, and into the future, and is collected and preserved for the greater good.

Our stewardship of these new collections pertaining to the current pandemic—like our conservancy of all the collections our predecessors acquired, organized, preserved, and passed down over decades since the establishment of the library in the early nineteenth century—is a distinct privilege. It reminds me that I only “discovered” that rare report years ago because colleagues long before me decided to acquire and preserve it, and their successors kept it safe for such future discovery.

That experience years ago has helped me become a better researcher. It has also helped me appreciate the excitement, meaning, and privilege of my stewardship for the greater good with an outstanding team at the NLM.

Jeffrey S. Reznick is chief of the History of Medicine Division of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.