Using Their Words

Established in 2013 by medical and undergraduate students, EUVMIS is one of the first service-learning programs in the country to train graduate and undergraduate students to serve as medical interpreters at free clinics in Atlanta's underserved communities, many of them predominately made up of new Americans and immigrants.

Student Volunteers Serve as Much-Needed Interpreters at Atlanta Medical Clinics

Since he was a small child, Angel Gonzalez-Valero 19C has understood how important it is to understand.

A first-generation American born in Austin, Texas, Gonzalez-Valero served as an interpreter for his parents, immigrants from Mexico, whenever they needed him to bridge the gap between their native languages.

“I always interpreted for them in every situation, from getting groceries to going to the hospital,” says Gonzalez-Valero, a senior chemistry major who is serving his third year as president of the student-run Emory University Volunteer Medical Interpretation Services (EUVMIS).

Established in 2013 by medical and undergraduate students, EUVMIS is one of the first service-learning programs in the country to train graduate and undergraduate students to serve as medical interpreters at free clinics in Atlanta’s underserved communities, many of them predominately made up of new Americans and immigrants.

“Some of the most profound experiences for me have been when I see my parents in the patients I am representing,” Gonzalez-Valero says. “It makes me think that, no matter the situation of the patient themselves or the severity of the diagnosis, those people deserve someone who will help them feel more at ease.”

Group Effort: The Emory University Volunteer Medical Interpretation Services organization was formed by a group of students to fill a critical need in the Atlanta area, where the number of non-English speakers has increased rapidly in recent years.

Currently the program has nine interpreters who are fluent in Spanish, and the group hopes to expand to provide Portuguese translation with its incoming class of ten student volunteers.

“In the Atlanta metro area, the vast majority of the low English proficiency population are Spanish speakers, about sixty percent,” says Gonzalez-Valero.

Student interesting in joining EUVMIS apply in the fall and are screened by the student executive committee before being chosen for the program. Unlike some volunteer groups, these students commit to a forty-hour training program, held for eight hours a day on five consecutive Saturdays, to certify them as medical interpreters.

The majority of the cost for the program is covered by a three-year seed grant from the Office of the Executive Vice President for Health Affairs in the Woodruff Health Sciences Center and funding from the anthropology department’s Global Health, Culture, and Society program, but students are required to make a $200 investment toward the training and course materials.

“We do our best to search for students who are driven and committed to the program. Many of our students are premed, but when reading the applications you can very clearly see whether the student wants to join the group for their resume or for personal reasons,” Gonzalez-Valero says. “The people who really have a connection to what we are doing tend to stick with it. We tell our new recruits that it is like adding another class to their schedule. There’s a lot of studying and a lot of commitment required.”

Early on a fall Saturday, Cesar Aguilar 19C arrived at the Good Samaritan Health Clinic in Atlanta, serving as both an interpreter and clinic coordinator, keeping the Emory School of Medicine students who staff the clinic updated on when other interpreters would arrive and assisting patients.

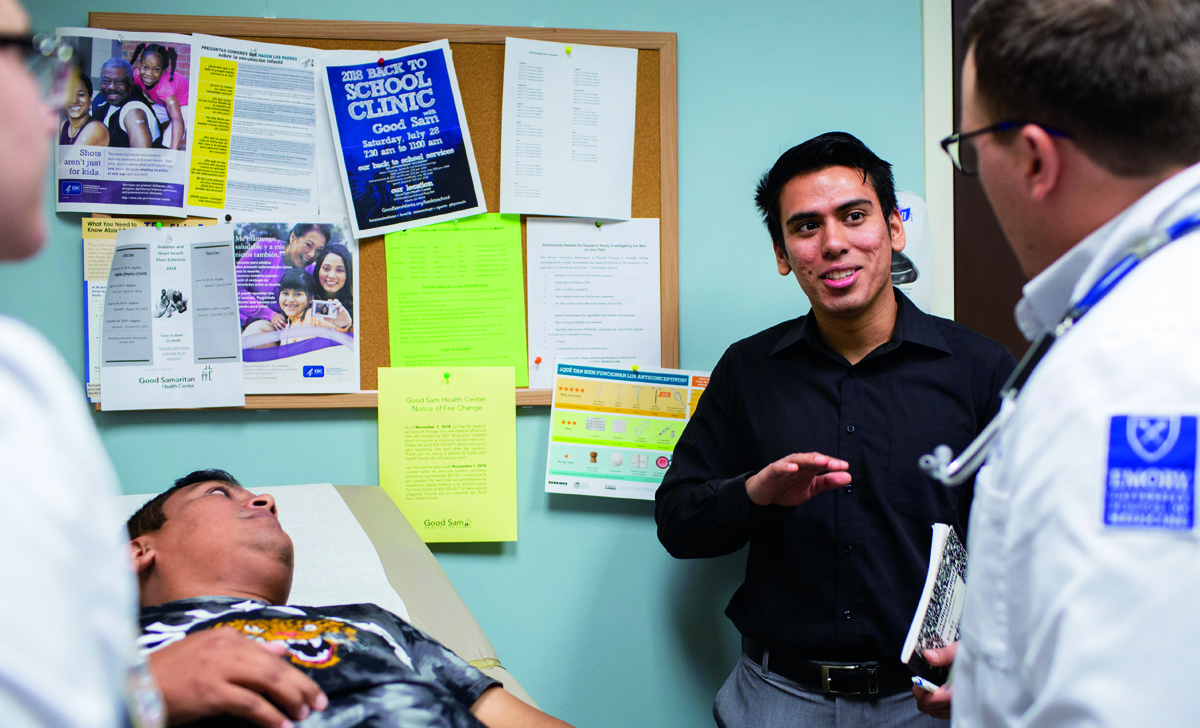

No Words: Aguilar, a wisecracking patient, and an Emory medical student are reminded that laughter is the same in any language.

His first client is a thirty-nine-year-old landscaper who has come in for headaches and throat pain. The man is visibly relieved when he realizes Aguilar is there to help him communicate with the doctors.

Carefully Aguilar listens to the doctors’ questions and relates them to the patient, then translates the answers back to the doctors. Although the process slows the examination a little, doctors are able to gather important details the patient shares with Aguilar, either in direct responses to their questions or in asides the patient shares with the interpreter.

In another room, a woman in her sixties needs her diabetes medication refilled, then relates that she works twelve-hour days cooking in a restaurant kitchen and that she has pain in her left shoulder that is preventing her from lifting her arm above shoulder level.

In rapid-fire Spanish she describes the pain, demonstrating by lifting and rotating her arm, grimacing when the pain prevents normal movement. Despite her pain, she smiles and laughs with Aguilar, cracking jokes in Spanish that set the young man chuckling. He relays them to the medical team, who smile and laugh with her, keeping her at ease.

“When you see a patient or their family members and they realize you speak Spanish, they get a smile on their faces because they know their voices are finally going to be heard and they will get the appropriate health care,” says Aguilar, who has been an interpreter since his sophomore year. Like Gonzalez-Valero, Aguilar often translated for his parents, who are originally from Mexico and El Salvador, while growing up in California.

He wants to go to medical school, so the experience is helping him learn the ropes early, but his interest goes beyond the academic.

“I see common threads with all of the patients. There is a serious problem with Spanish-speaking populations in terms of diet, incidence of cardiovascular disease, and high blood pressure,” he says. “This is something we need to help educate people about.”