The Honor Is All Ours

If you've ever wondered how honorary degrees happen, here's a brief history

University Archives

It was a moment that called for a poetic home run, or at least a good cut at a high-floating fastball—maybe something like Robert Frost’s “good fences make good neighbors.”

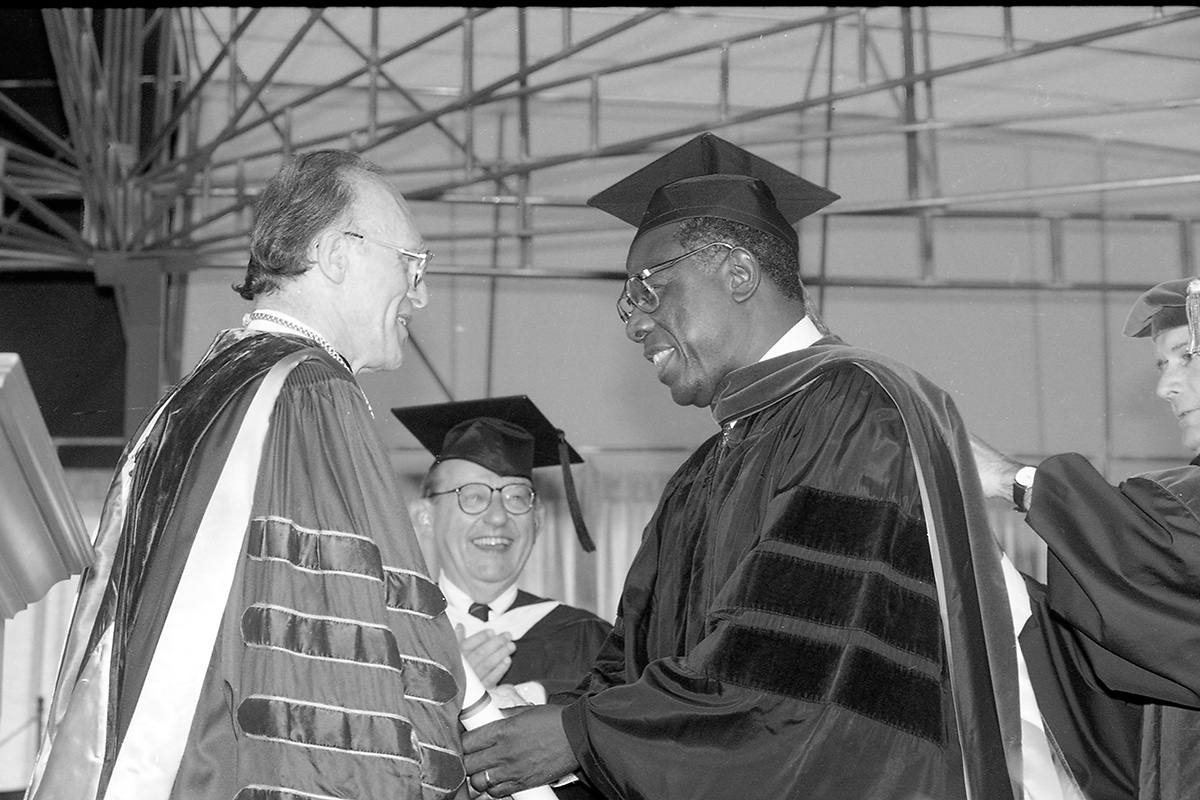

The provost was draping a doctoral hood over the shoulders of Henry Louis Aaron—“Hammerin’ Hank,” the home-run king—at Emory’s Commencement in 1995. Somewhere nearby the ghost of President Warren Candler may have hovered in disbelief. Not only had his policy against intercollegiate athletics given way completely, but here was his beloved university honoring a professional baseball player, of all people, with the honorary doctor of laws degree, of all things.

Atlanta’s hometown hero, though, did not just swat baseballs magnificently. Throughout his life, Aaron aimed to break down barriers and make civil rights a reality. This, Emory said, was worth recognizing with a degree that honored the law as well as the man.

As the university president read the accompanying tribute, the audience broke into applause at the line, “you showed good fences make good targets.” And thus, awarding its highest honor to a man who hit balls over a wall, the university refreshed a tradition sometimes viewed as soporific, time-consuming, and puzzling (litterarum humanorum doctor, honoris causa?).

But Emory at that moment also raised in many minds the question about how it decides who receives an honorary degree. Scanning the universe of memorable achievement, how does the university let its gaze alight on this scientist and this poet rather than that musician or that politician?

Since the awarding of the first honorary degree by the University of Oxford, in the fifteenth century, the practice has implied a two-way exchange of esteem. We, the university, proclaim you to have earned a degree without all the study, fees, and hoop-jumping we normally require, because you have done something great for humanity. You, in turn, elevate our status a bit by deigning to associate with us and lending us your prestige, now and for as long as your name graces our history and our website.

Recent history may suggest how this works. Emory was pleased, in 1992, to be one of only two US institutions to grant an honorary degree to Mikhail Gorbachev, whom Timemagazine had recently declared the “man of the decade.” Gorbachev had precipitated such change in the Soviet Union that he set in motion the ending of the Cold War. The Emory Commencement at which he spoke provided the occasion for a mini-summit, as Gorbachev met beforehand with former President and University Distinguished Professor Jimmy Carter to talk about the work of The Carter Center as a possible model for the Gorbachev Foundation.

On the other hand, it can be tricky to recognize the best in their fields while requiring that their lives reflect the university’s mission and vision. Although the intense public interest in seeing Gorbachev required fencing the Quadrangle for the first time to preserve seats for the graduates and their guests, one faculty member complained that Emory was besmirching its own honor by celebrating someone he considered an unrepentant Communist. Other faculty members have protested degrees for Mary Robinson, former president of Ireland; Ben Carson, brain surgeon and current secretary of Housing and Urban Development; Arnold Schwarzenegger; and Wernher von Braun, the rocket scientist who advanced America’s race to the moon but had been instrumental in the Nazi war effort.

It is difficult, however, to imagine protests against the earliest recipients of honorary degrees from Emory. The place was smaller then, the faculty largely of one faith if not one mind, and the students under strict parietal rules.

Emory awarded its first honorary degree, a doctor of divinity degree (DD), in 1846, at the seventh Emory Commencement (the sixth with actual graduates). The recipient was the Rev. William H. Ellison, a Methodist minister and a leader in establishing higher education in Virginia, Alabama, and Georgia. He thus was typical of those whom Emory recognized throughout the nineteenth century for their contributions to the church and to education. Indeed, many of the honorees (Oxford University prefers “honorands”) through Emory’s first seven decades were Emory faculty members and presidents.

Things have changed. The current guidelines of the Honorary Degrees Committee note that only in “extraordinary circumstances” will it consider “persons who have spent the greatest part of their careers as members of the Emory faculty or administration.” But the university still suggests its values and priorities with honorary degrees. For instance, the fourteen Nobelists with Emory honorary degrees include ten peace laureates (Jimmy Carter, His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama), two in literature, and one each in economics and medicine. While public servants and philanthropic business leaders tend to outnumber all others, writers also abound among the honored—appropriate for a university with a top-ranked undergraduate creative writing program.

With an entirely male faculty and student body well into the twentieth century, Emory took until 1930 to award an honorary doctorate to a woman, Tommie Dora Barker, the founding dean of the university’s library school, but that honor signaled that women’s intellect now helped shape the institution. Not until 1970 did the first African American receive an honorary degree, Benjamin Mays, the legendary president of Morehouse College.

Of the 594 honorary degrees Emory has awarded, the university has never changed its mind about any. While the process of nominating, evaluating, and choosing candidates for honorary degrees has changed slightly over the years, the Honorary Degrees Committee of the University Senate always has in mind two overriding criteria: is the nominee at the top of his or her game, and does the nominee play the game in a way that reflects the highest values of the university? For everyone from William H. Ellison in 1846 to the class of honorees in 2018, the answer clearly was yes.