Making Tracks

Anthony Martin follows in the footsteps of prehistoric birds

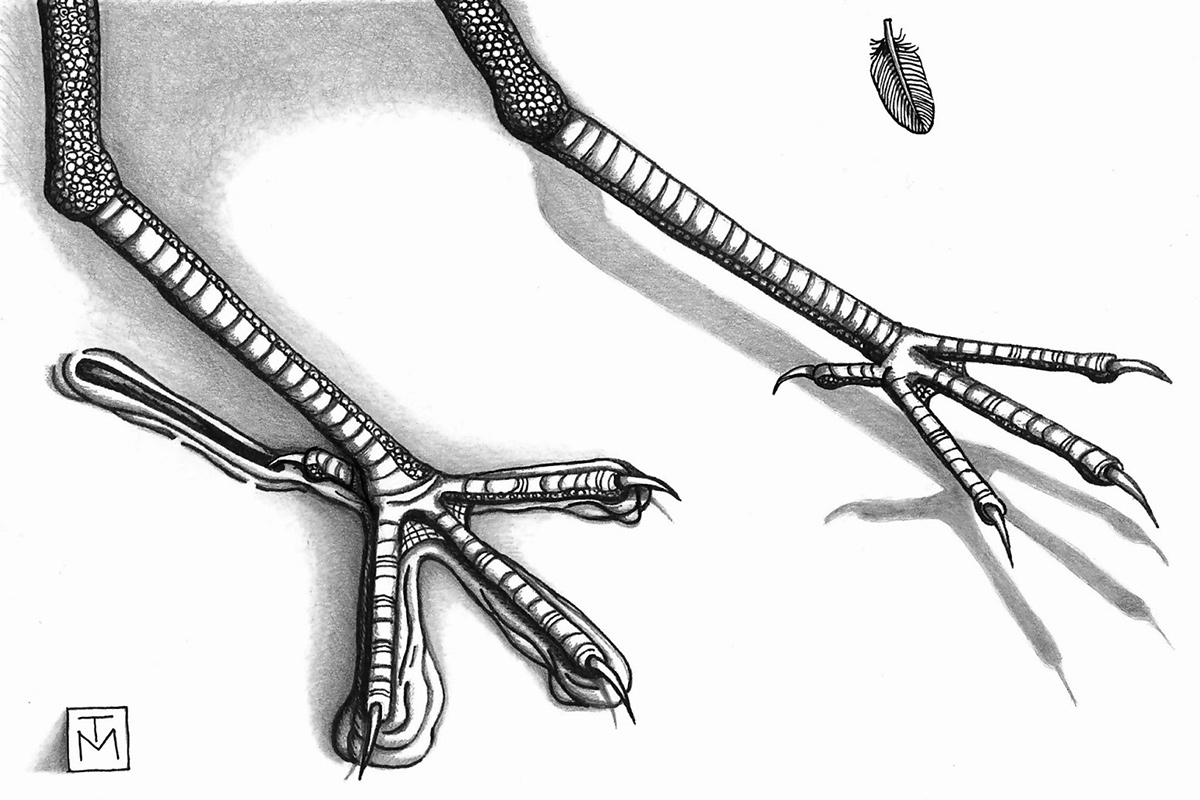

Illustration by Anthony Martin

Two fossilized footprints found at Dinosaur Cove in Victoria, Australia, were likely made by birds during the Early Cretaceous period, making them the oldest known bird tracks in Australia.

The journal Paleontology is publishing an analysis of the footprints led by environmental studies professor Anthony Martin, who specializes in trace fossils including tracks, burrows, and nests. The study was coauthored by Patricia Vickers-Rich and Michael Hall of Monash University in Victoria and Thomas Rich of the Museum Victoria in Melbourne.

Much of the rocky coastal strata of Dinosaur Cove in southern Victoria were formed in river valleys in a polar climate during the Early Cretaceous period. A great rift valley formed as the ancient supercontinent Gondwana broke up and Australia separated from Antarctica.

“These tracks are evidence that we had sizeable, flying birds living alongside other kinds of dinosaurs on these polar, river floodplains, about 105 million years ago,” Martin says.

The thin-toed tracks in fluvial sandstone were likely made by two individual birds that were about the size of a great egret or a small heron, Martin says. Rear-pointing toes helped distinguish the tracks as avian, as opposed to a third fossil track that was discovered at the same time, made by a non-avian theropod. A long drag mark on one of the two bird tracks particularly interested Martin.

“I immediately knew what it was—a flight landing track—because I’ve seen many similar tracks made by egrets and herons on the sandy beaches of Georgia,” Martin says.

Martin often leads student field trips to Georgia’s coast and barrier islands, where he studies modern-day tracks and other life traces, to help him better identify fossil traces.

The ancient landing track from Australia “has a beautiful skid mark from the back toe dragging in the sand, likely caused as the bird was flapping its wings and coming in for a soft landing,” Martin says. Fossils of landing tracks are rare, he adds, and could add to our understanding of the evolution of flight. Today’s birds are actually modern-day dinosaurs, and share many characteristics with non-avian dinosaurs that went extinct, such as nesting and burrowing. The theropod carnivore Tyrannosaurus rex had a vestigial rear toe, evidence that T. rex shared a common ancestor with birds.

Dinosaur Cove has yielded a rich trove of non-avian dinosaur bones from dozens of species, but only one skeletal piece of a bird—a fossilized wishbone—has been found in the Cretaceous rocks of Victoria. Martin spotted the first known dinosaur trackway of Victoria in 2010, and a few other tracks have been discovered since then. Volunteers working in Dinosaur Cove found these latest tracks on a slab of rock, and Martin later analyzed them.

The tracks were made on the moist sand of a river bank, perhaps following a polar winter.

“The picture of early bird evolution in the Southern Hemisphere is mostly incomplete,” Martin says, “but with these tracks, it just got a little better.”