Last

summer, with vacation in full swing, most sunny

afternoons found some twenty-five children who live at

Edgewood Court Apartments not at the pool or park, but

sitting quietly at tables in the small activity room,

reading. These youngsters participated in a summer reading

program started by an Emory College student, Tianna Bailey,

and her cousin, Georgia State student Maurice Shaffer.

“Throughout

our lives, a lot of organizations and people have invested

in us,” Bailey (left) explains. “We both received

full scholarships to college. We felt so blessed that

we wanted to give back to the community in some way. We

chose Edgewood Court Apartments because I have family

who have resided there for the last ten years, and my

cousin used to live there. We wanted to start in the community

where we grew up.”

“Throughout

our lives, a lot of organizations and people have invested

in us,” Bailey (left) explains. “We both received

full scholarships to college. We felt so blessed that

we wanted to give back to the community in some way. We

chose Edgewood Court Apartments because I have family

who have resided there for the last ten years, and my

cousin used to live there. We wanted to start in the community

where we grew up.”

Bailey’s

effort is exactly the kind of project Associate Professor

of Medicine Neil B. Shulman had in mind when he launched

Social Entrepreneurs at Emory, a start-up grant program

administered through the Volunteer Emory office. In 2000,

Shulman gave $2,000 to support students interested in

starting their own non-profit services, and five students

received $400 grants. Last year, fourteen Emory students

received ten grants for $200 to $400 each. The idea, says

Shulman, is that the students establish volunteer-based

programs and services that continue to have an impact,

even after the founders have graduated.

“I

always wanted to see something like this done,” Shulman

says. “In an academic institution, the professors

are in charge, and the students learn from the professors.

But I really feel there is a lot we can learn from the

students if we just empower them to take an idea they

had on their own and help them do it. It would be wonderful

to have a lot more people graduate from school who are

social entrepreneurs, starting their own non-profits for

social good that could even turn into a business and a

career for the student. With these small grants, these

students have had incredible impact.”

Students

can apply for grants as individuals, in small groups,

or with a student organization; the only requirements

are that they reach out to the community beyond Emory

and that the student founders have a concrete plan for

how they will continue in years to come.

Most

of Emory’s social entrepreneurs have been drawn to

working with Atlanta children who are in need or at risk,

says Hildie Cohen, director of Volunteer Emory. The services

themselves span a wide range, however, such as teaching

conflict resolution skills to fourth and fifth graders,

inviting elementary school kids to Emory for a day to

see what college is like, helping inner-city high school

students through the college application process, developing

an inner-city tennis program, and volunteering in the

juvenile court system.

“The

volunteer hours from the first year alone exceeded nine

hundred hours,” Shulman reports. “Students get

their friends and classmates to be involved. A number

have gotten newspaper coverage, and a couple have gotten

additional grants to become a separate non-profit. These

are students who are not just doing volunteer work, but

starting something real that may go on forever.”

Most

of the children at southeast Atlanta’s Edgewood Court

Apartments live in single-parent households, with several

siblings and young mothers who may work long hours. Before

Tianna Bailey set up IMAGE (I Must Achieve the Goal to

Excel), the free after-school program she and her cousin

conduct in the community “activity room,” many

of the children went home to watch TV in the afternoons,

played outside–unsupervised or possibly looked after

by older sisters or brothers–or just generally hung

around.

During

the school year, thirty-five of them now spend three afternoons

a week, from three to six p.m., at the IMAGE site, mostly

doing their homework with the help of volunteer tutors.

The tutors help them through any problems, check their

work, and make sure they are prepared for tests. Bailey

found forty volunteers to help with the program last year,

many of them Emory students and others from Georgia State,

Morehouse, and Georgia Tech. After homework time, the

volunteers usually organize a group activity that might

teach the children about conflict resolution, honesty,

or teamwork. The children also go on monthly field trips.

One

unique aspect of the program, Bailey says, is that it

encourages parent involvement. Parents are asked to volunteer

at least five hours a month. “They like the program,”

she says. “They know their kids will be safe and

doing their homework. This is subsidized housing and the

income level is not high. All of these kids are latchkey

kids.”

The

activity room, which the apartment management readily

agreed to let them use, is crowded with tables and chairs,

books and games, and a snack counter topped with huge

jars of candy. A sign on the wall outlines a few rules:

“No horseplaying. Mind your business. Be honest.”

There is a discipline system that the volunteers enforce,

Bailey says, with the most dire consequence for unruly

behavior being expulsion from the program.

Bailey,

who graduated this year, proposed the IMAGE project when

she was a sophomore. She returns to Emory this fall for

a graduate degree in education. She and Shaffer are also

seeking additional funding and support for IMAGE; they

have already received grants to continue the program.

Bailey

never loses sight of the program’s rewards. “We

had this fifth-grader last year,” she recalls, “who

was having trouble academically and emotionally. He was

being ridiculed and was to the point of giving up. We

worked with him and tried to build his confidence. By

the end of the year, his teacher sent a report saying

she didn’t know what was going on at home, but there

was a tremendous improvement in his behavior. She said

he had made a 180-degree-turn.”

The

more successful IMAGE becomes, the more work it takes

to keep it going. “What Maurice and I are learning,”

Bailey says, “is that this is like a business for

us. We are not being paid, but it’s like a dream

come true.”

I

left my home in Puerto Rico,

the

silent oceans,

the

placid mountains,

the

cool, soft nights.

So

begins “The Forgetful Island,” a poem by Renfroe

Middle School student Juan Cardoza Oquendo. The poem won

third place in the poetry contest featured in X-Change,

a magazine for elementary and middle school students founded

by Emory social entrepreneur Lauren Gunderson (above).

So

begins “The Forgetful Island,” a poem by Renfroe

Middle School student Juan Cardoza Oquendo. The poem won

third place in the poetry contest featured in X-Change,

a magazine for elementary and middle school students founded

by Emory social entrepreneur Lauren Gunderson (above).

“X-Change

is a magazine for you, about you, by, and with you. Inside

every issue will be stories about Atlanta kids, celebrities,

issues in our world, art, science, sports. It’s what

you care about. What’s cool. What’s exciting,”

Gunderson and co-editor Nishima Chudasama ’02C tell

their readers in the first issue. “It’s about

your writing, your interests, your lives, your creativity,

your opportunity to make a difference.”

Gunderson,

a junior, and Chudasama together developed the idea for

a kids’ literary magazine that would both inspire

young people and give them an outlet to express themselves.

“Basically, we got to talking about how we would

take some initiative for change, not just helping out,

but real long-term change in the community,” Gunderson

says. “For long-term change you want to hit kids,

so we decided that would be a good place to start.”

The

first two issues of X-Change caught on quickly with both

students and teachers in the eight Decatur public schools

where the magazine is distributed by hand. Produced simply

in black and white, the four-page publication is packed

with graphics and text, including poems by students, calls

for submissions, contest announcements with prizes, and

numerous facts and inspiring quotes from various artists

and writers. Ideally, Gunderson says, she would like to

feature about a dozen youngsters per issue. She also wants

to expand X-Change to reach other schools.

The

magazine never wavers from its target audience. The summer

issue offers a number of suggested activities for the

long vacation that are part creative exercise, part fun:

“Read a book and see the movie version!” or,

“Write a letter to yourself. . . . Next year open

it and see how you’ve changed.”

“The

magazine was born out of this desire to reach kids in

a way that is inspiring for them, but also makes sense

to them, in their own language,” Gunderson says.

“The huge overall goal is to celebrate kids who are

trying to do something creative. If you want to reach

a kid, the best way is to congratulate them on something

they’re already doing. Then they’ll say, what

the heck, I’ll keep doing it.”

When

Caren Kelleher was a child, she was part of

a special art class that produced a 3-D mural for a local

hospital in a suburb of Washington, D.C. The teacher worked

hard to encourage the kids’ creativity. “It

really pushed me, it gave me confidence, it was fun, and

I made great friends that way,” Kelleher says. “That

was the fundamental idea.”

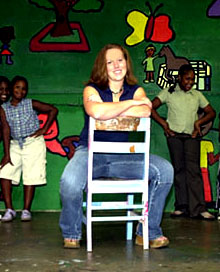

Now

Kelleher (left), a sophomore and one of Emory’s social

entrepreneurs, is trying to recreate that experience with

ARTreach Atlanta. Working with about thirty Emory volunteers

and a local group called Youth Art Connection, Kelleher

led an effort to transform an art room at the urban Warren

Boys and Girls Club in Cabbagetown last spring.

Now

Kelleher (left), a sophomore and one of Emory’s social

entrepreneurs, is trying to recreate that experience with

ARTreach Atlanta. Working with about thirty Emory volunteers

and a local group called Youth Art Connection, Kelleher

led an effort to transform an art room at the urban Warren

Boys and Girls Club in Cabbagetown last spring.

The

art room had not been cared for or cleaned up in about

a decade, Kelleher says. Their first task was to give

it a thorough cleaning. Then, she asked the youth who

use the club–about fifty children from the area,

age seven to thirteen–to draw their ideas of the

perfect art room. Out of a hundred drawings, she and the

other volunteers gathered ideas for a giant mural, then

let the kids paint it. The brightly colored, folk-art

style mural takes up an entire twenty-five-foot wall.

“The

kids were so excited to see that someone would actually

come to help with their art room,” Kelleher says.

“They were not using the room at all, they had no

organization and no teacher. I hope now they will find

a permanent art teacher.”

Kelleher

is planning similar long-lasting art projects for ARTreach

Atlanta in the future, including other boys and girls

clubs and a local children’s hospital. But she also

hopes to expand the program to provide art education and

creative opportunities to individual children and small

groups.

“Because

our organization is so young, it’s kind of hard to

see where it will go,” she says. “Fundraising

has been our biggest hurdle because art supplies are so

expensive. But I hope our volunteers can pair up with

the kids and work with small groups to promote art. They

really enjoy spending time with the children, tapping

into their creativity. Kids look at the world and to them,

it’s so new.”