|

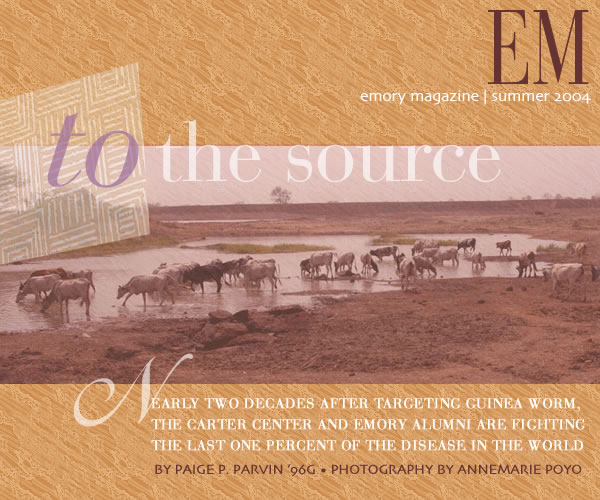

They say it hurts most at night, when the village is dark and quiet and there is nothing to take the mind away from the slender, whitish worm emerging from an open sore on the skin. Lukas, a young yam farmer in the Nkwanta district of Ghana, West Africa, slaps a dirty cloth at the flies swarming around a raw area on his leg as he describes the pain, saying he cannot sleep and is unable to work. When he had Guinea worm disease four years ago, he did not know what caused it; he thought his very village was the reason–that this was simply a place where Guinea worm happened, as it had happened to his family and his ancestors before him. Now, thanks to Emory’s institutional partner, the Carter Center, and several University alumni, he understands that the worm comes from the village’s stagnant, untreated water sources. This community lies in one of the most remote regions of Ghana, twelve teeth-rattling hours over a dusty, rutted road that winds north from the capital city of Accra. When trucks carrying visitors from the Carter Center approach at sunset one evening in early February, curious children come running from brown mud huts, all smiles, wearing a mystifying assortment of items: a Barbie pajama top, striped pants with one leg cut short, a bright swath of kente cloth, a filthy, frilly dress, or just a coating of red dust. A glance inside the huts reveals these children sleep on dirt and probably have never used an indoor toilet. Skinny goats and bedraggled chickens wander among them, picking their way around the cooking fires and the trash that litters the ground. Despite their apparent lack of almost everything, including safe water, the children shriek with laughter at images of themselves on a square-inch digital camera screen.

The Nkwanta district villages and others like them in northern Ghana are among the last one percent of endemic Guinea worm areas on earth. These have been called the world’s most forgotten people, which may explain why developed countries have paid little attention to Guinea worm disease despite its almost primeval loathsomeness. But part of the mission of the Carter Center, founded in 1980 by former U.S. President, Nobel laureate, and Emory University Distinguished Professor Jimmy Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, is to address those far-flung afflictions largely ignored by other non-government organizations. The ancient Guinea worm parasite, while not usually fatal to its human hosts, can grow up to three feet long inside the body before emerging slowly through a blister on the flesh. The disease is contracted by drinking water that contains the microscopic Cyclops flea, which eats and carries parasitic Guinea worm larvae. In the host’s stomach, the flea is broken down, leaving the male and female worm larvae free to cruise undetected through the body until they find one another and mate. The male dies, while the impregnated female grows not fat but long before emerging blindly into the African sunshine some nine months to a year later, typically on the lower limbs. The emergence of “the fiery serpent” causes a painful burning sensation, often sending victims to the nearest water source to soak the sore, which begins the cycle anew: when it hits the water, the worm releases thousands of new larvae.

For all its wiliness, Guinea worm can easily be stopped by filtering the tiny fleas out of contaminated water and keeping infected persons away from water sources. Efforts by the Carter Center, along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the World Health Organization (WHO), have helped reduce the incidence of Guinea worm disease worldwide from about 3.5 million cases in 1986 to fewer than thirty-three thousand reported in 2003. All the remaining cases are concentrated in thirteen African countries, the majority in Sudan, where civil war has made eradication attempts difficult. When Guinea worm is gone, it will be the first parasitic disease to be eradicated and the first sickness to be eliminated globally without a vaccine. Ghana harbors the second-highest incidence of Guinea worm disease, with some 25 percent of the current known cases–a challenge that prompted the Carters to pay a visit there in February along with WHO Director-General Lee Jong-wook and UNICEF Deputy Executive Director Kul Gautam. Despite the Carter Center’s early success in Ghana, the eradication program has been stalled for nearly a decade, with an increase in cases in the last three years. The Carters’ highly publicized appearance was meant to draw international attention to the country’s high rate of Guinea worm disease and make a serious push for increased eradication efforts. “We departed en route to Accra Tuesday afternoon with a mixture of anticipation and trepidation,” Carter wrote on February 3 in an electronic journal of the trip, which included stops in Mali and Togo. “Ghana was the first country in which Rosalynn and I ever visited endemic villages, and we’ll never forget seeing two-thirds of the total population incapacitated with the disease, many of them lying around under shade trees unable to walk. With our personal involvement and strong support from the national government, there were only 8,432 cases six years later, in 1994. There has been stagnation in Ghana’s efforts since then, and in the last three years the number of cases reported has risen from 4,739 to 8,283.”

“I wanted to do field-based work,” said Becknell, a lean young man with wild, bushy black hair and intense, piercing eyes. “I just like being outside, trying to work with the local people, building a strong team. I did it at Emory through Habitat for Humanity and Outdoor Emory–it seems very natural to me.” Part of Becknell’s job is trekking to remote areas by bike, boat, and on foot if necessary to search out cases of Guinea worm so they can be recorded and treated. His thorough surveys have resulted in a spike in the reported district case numbers, with more than five hundred new cases discovered in January alone. Much of the region Becknell oversees has virtually no potable sources of water such as wells or drilled boreholes, so convincing people to consistently filter the surface water they use is his best hope for a significant reduction in Guinea worm transmission. He has helped train more than forty Ghanaian zone coordinators, who in turn coach hundreds of grassroots volunteers to educate people on how to prevent Guinea worm. Becknell has come up with creative ways to communicate the Carter Center’s health messages, such as hosting festive evening programs in which educational skits are combined with music and dancing. He anticipated the Carters’ visit would bring added weight and importance to his work in the eyes of influential local leaders. “Behavior change is hard,” Becknell said. “In our country, millions die every year from smoking and eating fatty foods. One of the biggest indicators of success here is when someone asks me a question because they want to change their lifestyle. Seeing real changes in attitudes can really give a sense that what we’re doing is working.”

Dressed in a flowing turquoise robe, wearing a striped hat and round, dark sunglasses, the shrunken old chief sat enthroned in his hut on a stack of grimy cushions, his wrinkled feet propped on a scarred leather ottoman. Saaka’s hut was larger than most but not exactly opulent; besides some ceremonial objects adorned with feathers and fur, his only observable possession was a huge, plastic, battery-operated clock, set to the correct time, hanging above his open doorway. The ticking clock, arguably meant to keep the chief to some sort of schedule, seemed an ironic presence in Africa where time is famously fluid. Saaka told visitors he was preparing for the arrival of his “friend,” Jimmy Carter. “He is praying his friend will come and leave safely,” translated his linguist, through whom all the chief’s communication is funneled. “He is grateful [Carter] is coming so he will see for himself that there is no clean water.” Saaka had hit on one of the toughest obstacles to eradicating Guinea worm in Ghana: the people, understandably, want good water, not filters and instructions. But because clean water is scarce in many parts of Ghana, particularly during the dry season from October to March, the Carter Center’s eradication strategy relies heavily on water filtering. Digging deep wells and boreholes is one solution, but the process is costly and time-consuming, and boreholes can fall into disrepair. Instead, with the support of more than a dozen governments and private partners, the Carter Center has provided millions of white cloth filters to households in endemic areas, handing out nearly a half- million last year in Ghana alone. They also have distributed some nine million plastic pipe filters in Africa, which are worn around the neck on a string and can be drunk through like a straw. Another component of the eradication program involves treating stagnant water sources with the chemical Abate, which kills Guinea worm larvae but is not effective in large bodies of water.

“The people say, ‘We will eradicate Guinea worm when you dig a deep well’,” Carter said in a press conference during his visit. “‘The government should dig more boreholes.’ But you don’t have to have a borehole to eradicate Guinea worm. In many nations, we have completely eradicated Guinea worm without digging a single well. This requires education, teaching people, and surveillance. . . . The strategy works completely, but the number-one dependence has got to be on the filter cloth.” The strategy may be simple, but implementing it in a place where no one wears shoes or a watch can prove maddeningly difficult. The roadblocks to success are many and varied, from government resistance to village superstition. “The major underlying flaw in Ghana,” said Ernesto Ruiz-Tiben, technical director of the Carter Center’s Guinea worm eradication program, “has been poor supervision of the village-based health workers. In the last two or three years we’ve tried to correct the problems by providing additional resources to help create a cadre of personnel below the sub-district levels that allows for much better supervision . . . including technical advisers, both Ghanaian and ex-pats, to help strengthen intervention. We have also provided funding for additional vehicles, extra staff, and cloth filters enough to cover every household. In our view, Ghana has all the resources needed to have effective surveillance and the means to contain transmission from each case.”

“I can have ten things I want to get done, and if I get two of them accomplished, that’s a really good day,” Vaughn says. As a young, pretty, white woman working in rural Ghana, Vaughn has to be tough. Once, when she had spent an entire day watching Guinea worm extractions and a long, tangled worm suddenly spilled out of the incision in a boy’s ankle, she passed out, coming to a few minutes later as anxious faces hovering above her blocked the hot African sun. Another time the water reservoir at her tiny house ran dry on a Friday afternoon, leaving her without water for the weekend. She went to Tamale and bought dozens of “sachet waters,” clean water in plastic bags about the size of a Ziploc baggie. “You learn to be resourceful,” she says. With offices in Tamale as a home base, Vaughn works closely with a web of local Carter Center staff and volunteers and with members of the Peace Corps and the Red Cross to monitor Guinea worm in her district. The day before the Carters’ visit, Vaughn drove to Diare, one of the villages she oversees, to check on the area containment center, a makeshift clinic where infected residents are encouraged to stay until the Guinea worm has emerged. Thirty-seven cases had been reported at the Diare center in January. The only treatment for those with emerging worms is to keep the afflicted area clean and bandaged to prevent infection, wrap the worm around a matchstick, and carefully turn it a little each day. The process can take as long as two months, depending on the length of the worms and how many are emerging; people have been known to host more than fifty worms at once, although to have more than a few is rare. Breaking an emerging worm will cause it to pull back into the body, where it will die, calcify, and possibly cause deformities. Abukari Abukari or “AA,” a district coordinator for the eradication program, greeted Vaughn in Diare, where he was treating the day’s Guinea worm patients. An old woman, cradling a shriveled arm that she explained had been crushed in a long-ago lorry accident, quietly described the pain of the worm as “unbearable.” A boy with enormous eyes, who looked to be about three years old but was said to be six, was visiting the containment center for the first time with a Guinea worm emerging from the top of his foot. When AA tugged gently at the stringlike worm, the boy began to cry helplessly; his mother, standing by, put her hand to her mouth and looked away. After his foot was cleaned and neatly bandaged, he received candy, but he never smiled. The challenge, says AA, is convincing people to alter their behavior permanently. “How do you get the people to change their attitude?” he says. “They untie the bandage, they say it was too painful. You go to a dam site and say, don’t go in the water, and the next day they will be there again. But eradication will take the commitment of everyone. When your neighbor is sick, you are all sick. One person cannot achieve an aim without everyone.” Until recently, most of the volunteers trained in Ghana’s Guinea worm eradication effort were men. But about two years ago, the Red Cross in particular began to teach women how to prevent the disease in their communities. Women are the ones who fetch water for their families each morning, often walking several miles during the dry season to scoop from a pond that might supply several villages as well as wild animals and livestock–mainly bony cattle–who roam freely in and around the water. The women typically use a calabash, or bowl-like gourd, to fill a fifteen-gallon metal tub, which they then help one another to hoist up to the coiled cloth on their heads for the walk back home. In the evening they must make the trip again. Now hundreds of women in rural Ghanaian villages are charged with helping to make sure the water used in their compounds is Guinea worm free. They show others how to fit the cloth filters, which resemble white shower caps for giants, over the lip of the large clay drums used for water storage in the villages, then pour the pond water through them. The volunteers also inspect the filters for holes and help replace them when needed. They have become a sort of cadre of Guinea-worm police, visiting designated households regularly to make sure the water is being filtered before use. Their uniform is brilliantly dyed kente cloth–a welcome splash of color against the backdrop of drab dust and scrubby trees.

Alun Alid, a forty-two-year-old woman with clear eyes and a strident voice, spends three days each week visiting houses to check them for Guinea worm. She said she was chosen for the role by her community because they knew she could do it; she is hardworking, and she loves Diare. Her people filter well, she says, because she used to stand and look at them while they filtered it–a significant incentive. She also monitors the dam, Diare’s water source, to make sure no one with Guinea worm enters it and that no one drinks straight from it. “When I am at the dam, no one will enter the water,” she says proudly.

Buzaza said that Guinea worm is “embarrassing” to Ghana, that he would be ashamed if someone in his family contracted the disease. But apparently not everyone feels the same. “If you go to a house and ask if they are filtering, they can filter very nicely for you to see, but they don’t practice it,” he said. “Because of this, you can’t sleep.” Still, Buzaza is optimistic about the success of the Guinea worm program, especially since adding women volunteers has made a great difference in his ability to monitor cases in his area. The women report new cases to him every day. He described a woman who came to one of his containment shelters with twenty worms and stayed forty-four days. When she was released, her husband and children came to him to say thank you. “She was very happy,” Buzaza says. “She said, was there some magic? She thought Guinea worm was from witchcraft. Now she knows it is from water.” Eradication has become a personal dream for Buzaza, and he had high hopes for President Carter’s visit the following day. “President Carter’s visit is very, very important,” he said. “His coming will let all of us work harder, we will overwork ourselves to eradicate Guinea worm in northern Ghana. When the worm is gone, we will be very, very happy. We will grow and be fatter.” On the morning of the Carter delegation’s arrival, the hot Saharan wind, the harmattan, blows ceaselessly across the field near Dashei, rippling the pond where the Carters will watch a water filtering demonstration. The ground has been dampened to control the dust, but clouds still billow behind the convoy of fifteen SUVs rolling across the grass toward the site, looking as out of place as a line of donkey carts plodding down Atlanta’s busy Peachtree Street.

In Dashei, the Carters visit Guinea worm victims at the containment center, stopping to talk to several of them in a concerned, unhurried way. “When questioned,” Carter later wrote in his journal, “even the youngest ones would show us scars on their arms and legs from infections during previous years. Forty percent of all cases are children.” The Carters watch a class of children being educated about the disease. Another group of schoolchildren sings a song for the guests with the chorus, “Guinea worm, go away.” They wear T-shirts that say: “I want to be in school. I don’t want to have Guinea worm again.” “We have come here on many occasions in the past to visit your great country,” Carter later told a group of reporters. “This time, we have come almost exclusively to address the problem of Guinea worm disease. Still this morning, when we visited the village, we were saddened, with tears in our eyes, to see this terrible worm coming out of little children’s bodies. This is unnecessary.” In the center of Dashei, excitement is mounting as a thousand villagers make ready for the Durbar, the celebration planned in honor of their special guests. The crowd, which includes dozens of area chiefs in colorful, locally woven regalia, sits on benches around a large arena of red dust in a setting that brings to mind an American-style rodeo. Traditional African dancers shake a tribal rhythm with belts around their ankles–instruments which once would have been made musical with dried beans or seeds, but now rattle with lengths of light metal chain. Signs and banners proclaim, “Welcome, President Carter. You have brought us hope.” The Carter delegation takes their seats on a shaded platform and speeches are made by each leader, including Ghana’s Minister of Health, Kweku Afriyie. “Never before has a president of the United States stood on this ground,” Afriyie says. “The government of Ghana takes the issue of Guinea worm very seriously.” When Carter takes the podium under the blazing sun, a ripple of respect and applause seems to bring the crowd to attention. “Ghana has wonderful people joining us in this effort to eradicate Guinea worm,” Carter tells them. “I want to especially thank the women of this country for the wonderful work they have done. “Next year I want to receive a report on this community that says there is zero Guinea worm,” Carter continues. “All of you are our brothers and sisters. We care for you. We wish you well. We want you not to have Guinea worm in the future.” After he speaks, Carter is presented with the traditional attire of an area naa, a chief, and given the name Jantong Malgu-Naa, “the development chief.” He readily dons the striped robe and hat; now the real celebration will start and continue on into the night, long after the Carters have boarded their plane for Accra. As the drumming grows louder, President Carter begins to trot and spin around the dust circle at his hosts’ urging, shaking a long hair whisk–a symbol of great authority–over his head. The people of Dashei shout their approval as, with a red face and a wide grin, the newest naa begins the dance

|

Emily

Howard ’97Ox-’99C (at left, with Nwando Diallo), coordinator

of public relations for the Carter Center’s health programs

and the lead organizer of this trip for staff and media, quickly

attracts a crowd of friendly locals with her fair skin and tall,

slender build. She points out that a half-dozen of the villagers

were visibly infected with Guinea worm; many others bear its scars.

This is the second time Howard has traveled to Ghana for the Carter

Center, which has been battling Guinea worm here since 1988. “The

first time I saw an actual, live Guinea worm, I cried,” she

says.

Emily

Howard ’97Ox-’99C (at left, with Nwando Diallo), coordinator

of public relations for the Carter Center’s health programs

and the lead organizer of this trip for staff and media, quickly

attracts a crowd of friendly locals with her fair skin and tall,

slender build. She points out that a half-dozen of the villagers

were visibly infected with Guinea worm; many others bear its scars.

This is the second time Howard has traveled to Ghana for the Carter

Center, which has been battling Guinea worm here since 1988. “The

first time I saw an actual, live Guinea worm, I cried,” she

says.

Emory

graduate Stephen Becknell ’00C-’02MPH (left) has

lived and worked in the problematic Nkwanta district for two years

as a technical assistant with the Carter Center’s Global 2000

Guinea worm eradication program. Despite the lack of electricity,

telephones, e-mail, or reliable roads, Becknell says he likes working

at the community level because “That’s where the action

is.

Emory

graduate Stephen Becknell ’00C-’02MPH (left) has

lived and worked in the problematic Nkwanta district for two years

as a technical assistant with the Carter Center’s Global 2000

Guinea worm eradication program. Despite the lack of electricity,

telephones, e-mail, or reliable roads, Becknell says he likes working

at the community level because “That’s where the action

is. Two

days before the Carters’ arrival, Jantong-Wura Ewontogmah Saaka

(left), chief of the northern village Dashei and eighteen surrounding

villages, welcomed guests from the Carter Center who had come to

help prepare for the prestigious visit. The Carter delegation was

scheduled to inspect a water site in Dashei, attend a community

celebration, and then proceed to nearby Tamale, a good-sized town

in northern Ghana, for a meeting with national health officials

to discuss the progress of Guinea worm eradication strategies.

Two

days before the Carters’ arrival, Jantong-Wura Ewontogmah Saaka

(left), chief of the northern village Dashei and eighteen surrounding

villages, welcomed guests from the Carter Center who had come to

help prepare for the prestigious visit. The Carter delegation was

scheduled to inspect a water site in Dashei, attend a community

celebration, and then proceed to nearby Tamale, a good-sized town

in northern Ghana, for a meeting with national health officials

to discuss the progress of Guinea worm eradication strategies.

Rebekah

Vaughn ’94Ox (left), a technical assistant for the program,

lives and works in the areas surrounding Tamale. She spends most

days bouncing in a white truck from village to village on roads

the same red hue as her native Georgia clay, trying to mark tasks

off an ever-changing Guinea worm to-do list. She might spend hours

locating a chain for a volunteer’s motorcycle or waiting for

the proprietor of Tamale’s lone pharmacy to return so she can

stock up on gauze for a Guinea worm containment center.

Rebekah

Vaughn ’94Ox (left), a technical assistant for the program,

lives and works in the areas surrounding Tamale. She spends most

days bouncing in a white truck from village to village on roads

the same red hue as her native Georgia clay, trying to mark tasks

off an ever-changing Guinea worm to-do list. She might spend hours

locating a chain for a volunteer’s motorcycle or waiting for

the proprietor of Tamale’s lone pharmacy to return so she can

stock up on gauze for a Guinea worm containment center.

Buzaza

Amadu Dauda (left) is a former Guinea worm volunteer who was promoted

to area coordinator in Vaughn’s district. The two work together

almost daily, and Vaughn is frequently invited to share the evening

meal with his family. In khaki pants and a crisp white shirt, Buzaza

manages to look cool despite the withering heat; he carries a CDC

backpack and rides a sporty motorbike, with a stack of filter cloths

bungee-strapped on the back, to five or six villages each day. His

fourteen years of work in the eradication program recently earned

him an award for being the best coordinator in the district.

Buzaza

Amadu Dauda (left) is a former Guinea worm volunteer who was promoted

to area coordinator in Vaughn’s district. The two work together

almost daily, and Vaughn is frequently invited to share the evening

meal with his family. In khaki pants and a crisp white shirt, Buzaza

manages to look cool despite the withering heat; he carries a CDC

backpack and rides a sporty motorbike, with a stack of filter cloths

bungee-strapped on the back, to five or six villages each day. His

fourteen years of work in the eradication program recently earned

him an award for being the best coordinator in the district.  President

and Mrs. Carter, their son Jeff, WHO Director-General Lee Jong-wook,

and UNICEF Deputy Executive Director Kul Gautam gather at the edge

of the water to watch a village woman and Red Cross volunteer demonstrate

how to collect and filter water. Leaning forward, Mrs. Carter, wearing

a salmon-hued suit, straw hat, and large sunglasses, helps her scoop

the water into a metal tub. A little boy, wearing the local school

uniform of orange and brown, then shows the visitors how to use

the pipe filter around his neck, kneeling on the rocks in the shallows

to drink right from the pond. Soon this muddy watering hole will

dry up completely, and the women of the village will have to walk

fourteen miles for water each day.

President

and Mrs. Carter, their son Jeff, WHO Director-General Lee Jong-wook,

and UNICEF Deputy Executive Director Kul Gautam gather at the edge

of the water to watch a village woman and Red Cross volunteer demonstrate

how to collect and filter water. Leaning forward, Mrs. Carter, wearing

a salmon-hued suit, straw hat, and large sunglasses, helps her scoop

the water into a metal tub. A little boy, wearing the local school

uniform of orange and brown, then shows the visitors how to use

the pipe filter around his neck, kneeling on the rocks in the shallows

to drink right from the pond. Soon this muddy watering hole will

dry up completely, and the women of the village will have to walk

fourteen miles for water each day.