FOR

THE FIRST TIME

in more than half a century, this fall’s elections promise

a genuine tug-of-war between parties for control of Congress,

and an Emory professor says the South is at the epicenter of

this political power struggle. It should come as little surprise

to Southerners that their region’s political landscape

has shifted dramatically in recent years, with the Republican

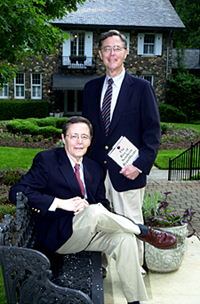

party making unprecedented gains. Merle Black, Asa G. Candler

Professor of Politics and Government (seated in photo), and

his twin brother, Earl Black, Herbert S. Autrey Professor of

Political Science at Rice University, trace The Rise of Southern

Republicans in their latest book, the last of a trilogy of Southern

political analyses.

FOR

THE FIRST TIME

in more than half a century, this fall’s elections promise

a genuine tug-of-war between parties for control of Congress,

and an Emory professor says the South is at the epicenter of

this political power struggle. It should come as little surprise

to Southerners that their region’s political landscape

has shifted dramatically in recent years, with the Republican

party making unprecedented gains. Merle Black, Asa G. Candler

Professor of Politics and Government (seated in photo), and

his twin brother, Earl Black, Herbert S. Autrey Professor of

Political Science at Rice University, trace The Rise of Southern

Republicans in their latest book, the last of a trilogy of Southern

political analyses.

Once

a staunchly Democratic region, the South has produced an increasingly

more complex mix of voters since the 1960s. The Blacks credit

this transformation largely to what they call the two “Great

White Switches.” Not surprisingly, the brothers write,

“The central political cleavage, as ancient as the South

itself, involves race.”

The

first switch took place in 1964, when Republicans nominated

Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater as their presidential candidate.

Goldwater, who boasted a strongly anti-civil rights record,

attracted scores of racist white voters while virtually severing

the already-tenuous ties between Republicans and African Americans.

In a shift that upset a hundred-year-old apple cart, more Southern

whites voted Republican than Democrat in that election, setting

a new precedent that has held for every presidential contest

since.

The

second switch occurred midway through Ronald Reagan’s presidency.

Up to that point, ex-Union states still shared a political identity

largely carved out more than a hundred years ago by the Civil

War, the Blacks argue. Born in the North to Lincoln and his

ideological successors, the Republican party held sway in the

Northeast, the Midwest, and the West, but the South was solidly

and impenetrably Democratic. In the 1980s, however, more Southern

whites began to identify as Republican rather than Democrat.

“The

growth of the Republican party in the South was stimulated enormously

by the Reagan presidency,” Merle Black said, at a May breakfast

forum hosted by Emory, where he appeared with his brother. “This

was one of the most striking examples of partisan realignment

ever, and it was a huge change for the South. At this point

the Democrats really got religion that they were indeed the

minority party. ‘White conservative Democrat’ became

almost a contradiction in terms.”

Between

them, the Black brothers possess an almost encyclopedic knowledge

of the people, political races, and polling trends that contributed

to Republicans’ recent Southern success. Through colorful

text and graphs they literally chart the party’s remarkable

progress in the South over the last fifty years.

In

1950, for instance, there were no Republican senators and just

two Republican representatives–of 105– from the South

in Congress. In 2000, Republicans made up the majority of the

South’s elected voice in Congress: fourteen of twenty-two

officials in the Senate and seventy-one of 125 in the House.

The

result, says Earl, is that “For the first time in a century,

we have a two-party system that is nationalized. This has tremendous

implications for national politics . . . and the South is the

epicenter of this struggle for control. In the South, either

party is perfectly capable of winning any election in any state.

This is a very competitive situation.”

A

newly competitive South, according the the Blacks, means a newly

competitive nation. Since the Great Depression, Democrats have

reigned supreme in Congress. But this year’s congressional

races guarantee nothing but unpredictability. What this rise

of Southern Republicans means for both regional and national

challenges like race relations, class division, and economic

and political health, only time will tell. –P.P.P.