|

ELEVEN-YEAR-OLD

Nancy Jean Howe

is playing hoops in her Sandy Springs driveway, swishing a few

baskets while waiting to go to soccer practice. She’s a

natural, moving with an effortless grace not often seen in lanky

fifth-graders. ELEVEN-YEAR-OLD

Nancy Jean Howe

is playing hoops in her Sandy Springs driveway, swishing a few

baskets while waiting to go to soccer practice. She’s a

natural, moving with an effortless grace not often seen in lanky

fifth-graders.

Whether

playing second base on a boys’ baseball team or winning

a race at school, Nancy (left) thrives on the competition. “I

just feel confident in myself that I can do it,” says the

freckled, fair-haired athlete, who has a shelf full of sports

trophies in her bedroom. Her prize possession is a baseball

with a date inscribed on it: May 20, 2000.

“That

was the game,” she recounts proudly, “where I did

some really good fielding on a grounder and threw it to first

base and the coach said, ‘Now that’s how to play baseball!’

’’

Nancy,

who was born without a full diaphragm and almost no left lung,

has far surpassed anything doctors at Egleston Children’s

Hospital/Children’s Health Care of Atlanta thought she

could achieve. “They told us she would never play sports

or be an opera singer,” says Jean Hetzel, Nancy’s

mother. “In fact, when we first brought her home when she

was two months old, we weren’t even supposed to let her

cry.”

If

Nancy had been born just a few years earlier, she almost surely

would have died. But because of rapid advances in neonatology,

babies born prematurely or with severe medical problems have

a good shot at not only surviving, but thriving. “We’re

just happy to be able to treat her normally,” says her

father, Jeff Howe.

Nancy’s

good health is the result of a series of high-tech medical interventions.

She lifts up her T-shirt to show off the six-inch, pale white

scar stitched across her left ribcage up to her breastbone,

a reminder of life-saving surgery when she was two days old.

Born

at Northside Hospital in Atlanta on June 11, 1991, Nancy is

the second daughter of Hetzel, a kindergarten assistant at Highpoint

Elementary, and Howe, a chef at The Weather Channel. Hetzel’s

pregnancy had been routine, and the baby was full-term—seven

pounds, with a full head of brown hair. But just seconds after

delivery, when her lungs were supposed to take over supplying

oxygen for her body, Nancy turned blue and didn’t cry.

“Everyone

was really quiet. Then the room filled up with the people you

don’t want in the delivery room with you,” Hetzel

remembers, “and they took her from us.”

Nancy

had a diaphragmatic hernia, which occurs in about 1 in 3,000

live births; her intestines had pushed up into her chest where

her left lung should have developed.

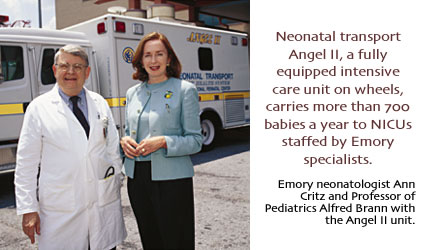

She

was taken to Northside’s NICU and hooked up to a ventilator.

After X-rays showed a left lung the size of a thumbnail, she

was taken by neonatal transport—Emory’s Angel II —to

Egleston Children’s Hospital on Clifton Road, where Emory

neonatologist J. Devn Cornish took charge of her care. Within

twenty-four hours, she had had two surgeries. Doctors immediately

fashioned an expandable Gore-Tex patch and attached it to her

ribs to act as an artificial diaphragm, and she was placed on

extra corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO,) an innovative procedure

Egleston had begun performing just the year before. Tubes ran

from a vein in Nancy’s neck to the cylindrical device—a

scaled-down version of a heart-lung machine—that put oxygen

into her blood. She stayed on ECMO for thirteen days, with the

hope that her existing lungs would expand and heal enough to

take over the job.

“It

all happens so fast, your brain doesn’t have time to register

all the possible complications,” Hetzel says. “We did

know she had less than a 10 percent chance of living. We couldn’t

even hold her. All we could do was touch the top of her head.”

ECMO

is a very high-risk, invasive procedure, says Cornish, who came

to Emory in 1990 to establish Egleston’s ECMO program after

starting similar programs in San Antonio and San Diego. “It’s

clearly a treatment of last resort,” he says. “But

there are circumstances where the potential benefits far outweigh

the risks, and this was the case with Nancy.”

Nancy

was the third of three babies with diaphragmatic hernias treated

with ECMO at Egleston and the first to survive. She was weaned

off the ventilator—a landmark for NICU babies—around

the Fourth of July and went home in mid-August.

Hetzel

flips through a photo album filled with Polaroids from Nancy’s

two months in the unit: it begins with a sedated baby attached

to a tangle of tubes and ends with a plump, smiling toddler

playing with her four-year-old sister, Abby.

Egleston’s

“New Beginnings” calendar for 1993 featured a round-eyed,

eighteen-month-old Nancy on the cover, and the hospital’s

1995 holiday cards had four-year-old Nancy’s green handprint

fashioned into wreaths on the front. She had become a living

symbol of what high-level NICUs can offer critically ill babies:

a future.

The

NICU at Egleston Children’s Hospital, on Emory’s main

campus, is one of three in the Atlanta area staffed by Emory’s

sixteen neonatologists: two level III units, at Crawford Long

Hospital in midtown and Grady Memorial Hospital in downtown,

and a level IV unit—the highest level of neonatal care

available—at Egleston.

Egleston

specializes in the toughest neonatal cases in the region: infants

who need state-of-the-art surgery or the most complicated treatments.

Eleven babies can be cared for in the intensive care unit (up

to three on ECMO,) and ten more in the intermediate care unit.

On any given day, the staff could be dealing with brain hemorrhages,

undeveloped lungs, severe infections, or cardiac problems.

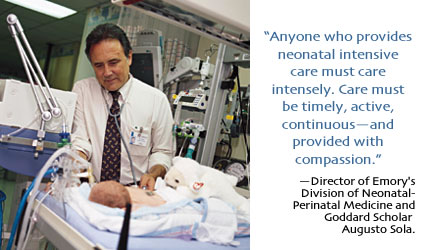

“Egleston

offers everything a baby could require,” says Augusto Sola,

director of Emory’s Division of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine

and a Goddard Scholar, who came to Emory last year from Cedars-Sinai

Medical Center in Los Angeles. “Truly, the babies we care

for at Emory have good outcomes. But Georgia is still fourth

from the bottom nationally in terms of infant mortality, so

we have a long way to go in improving education, prenatal care,

outreach, and access to care. If these little babies and their

mothers could make a demonstration, and hold protests with signs,

they might get the funding and attention they deserve.”

NEONATOLOGY

IS A FAIRLY MODERN SCIENCE

which, for centuries, was deemed unnecessary: frail, sickly

babies were “meant” to die, just as the fit and strong

should survive, so that society would not be burdened by the

lame or the constitutionally weak.

Even

after a human incubator was invented in the late 1880s in France,

premature infants were seen as little more than curiosities.

Sideshows at international expositions and fairs began featuring

“child hatcheries,” which attracted long lines of

visitors willing to pay to see tiny babies in incubators complete

with air filtration, humidifiers, and monitors. To everyone’s

surprise, the babies survived, and hospitals around the world

began using these devices.

During

the 1950s, heated Isolettes, made of clear Plexiglas, replaced

heavy wooden and metal incubators, and in the 1960s, ventilators

were used to pump oxygen-enriched air directly into premature

infants’ lungs, which became the standard treatment for

respiratory distress.

The

need for better treatments for premature infants received national

attention and increased research funding in 1963, after President

John F. Kennedy’s third child, Patrick, was born six weeks

early and died of respiratory distress syndrome.

Neonatology

is now one of sixteen subspecialties in pediatrics, requiring

three years of additional study after becoming a pediatrician.

It’s a demanding specialty, both in skills and stamina—high-risk

births and crises in newborns seldom occur during normal business

hours. For Emory’s neonatologists, this means rotating

shifts and occasional weekend and night duty, in addition to

training residents and fellows, giving lectures, and doing research.

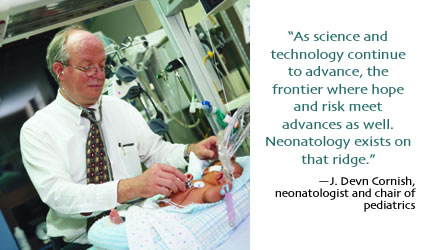

Cornish,

now chair of pediatrics at Emory, still works a neonatology

on-call shift once a month. “The last weekend I was on,

I started at 7:15 Saturday morning and got home at 7 o’clock

Monday night, with a few hours of sleep on the floor of my office

at Grady,” he says. “That’s what neonatology

is often like—pretty grueling.”

Still,

there are considerable rewards: the fast pace, the intellectual

challenge, the immediacy of critical care, and the patients

who come back to visit, a little taller each year

AS

AN URBAN, PUBLIC HOSPITAL,

Grady Memorial’s main mission is to provide health care to

Atlanta’s poor—it is obligated to accept any patient.

About half of Grady’s patients are covered by Medicare or

Medicaid.

Grady

is also a teaching hospital, with what the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s

Cynthia Tucker calls a “hard-working, top-notch staff struggling

to deliver top-quality care under difficult circumstances.”

On Grady’s fifth floor is the first, and still one of the

largest, special-care nurseries in Atlanta, with forty intensive

care beds and thirty-eight intermediate care beds.

The

hospital’s maternal-fetal medicine section receives high-risk

transfers from other obstetricians in the state, and the hospital

also sees a large number of disadvantaged women, addicts, or

immigrants who received little or no prenatal care. This results

in a higher than average number of premature, low-birth-weight

infants: About 15 percent (twice the state average) of the 4,500

infants born annually at Grady are younger than thirty-seven

weeks gestation or weigh less than 2,500 grams (five pounds,

eight ounces.)

“Grady

sees a very diverse patient population and a high-risk maternal

group,” says Susie Buchter, medical director of Grady’s

NICU, who joined the Emory faculty in 1984 after finishing her

fellowship in neonatology here. “But every child is given

the care they need.”

This

afternoon, there are twenty-three babies in the dimly lit NICU,

lined up against the wall in aquarium-sized, Plexiglass incubators

and surrounded by a battery of heart monitors, ventilators,

heaters, and humidifiers. Long strands of plastic tubing seem

to tether these fragile, naked infants to the physical world—almost

all premature babies younger than thirty-two weeks must be intubated

and placed on ventilators, since their lungs are not yet fully

developed, and many have IVs or feeding tubes, since they’re

too small or ill to nurse or take a bottle.

Highly

skilled neonatal nurse practitioners and bedside nurses (who

take care of three to four infants at most) are with the babies

around the clock, while scores of doctors, respiratory therapists,

nutritionists, and other specialists circulate through the NICU,

doing rounds, checking vitals, responding to alarms, updating

charts, consulting with small clusters of anxious parents and

grandparents.

“The

babies require ongoing, daily assessment,” says Ira Adams-Chapman,

the Emory neonatologist working at Grady this afternoon. She

monitors the machines, but also relies on hands-on exams to

check for heart problems, apnea (premies have a tendency to

“forget” to breathe), or distended abdomens. “Things

constantly come up with these kids—infections or complications—you

can never really trust them.”

A

calm, quiet efficiency emanates from Adams-Chapman, who came

to Emory in 1998 from a fellowship in San Diego. She was drawn

to neonatology for its “critical care aspect, but also,

because most of our kids are able to go home. And the babies

are here for a while, so we get to know them and their families

and establish relationships.

Ideally,

neonatologists become involved with the family before the baby

arrives. By using prior birth histories, ultrasounds, amniocentesis,

and other prenatal diagnostic tests, many high-risk births can

be anticipated.

This

was the situation with Aicha Keita, originally from Mali, West

Africa, who had seven previous miscarriages and one living child.

Doctors at Grady decided to give Aicha steroid shots during

her most recent pregnancy to strengthen the baby’s lungs

in utero. At twenty-seven weeks, Keita developed pre-eclampsia

(a condition involving high blood pressure), which forced a

Caesarean section. Abdelkader “Kader” Keita, three

months early and weighing one pound, four ounces, was whisked

away to the NICU, where he was placed on a ventilator.

Premies

have two ages: one based on the day they were actually born,

the other on the date they would have been born if they had

been full-term. Often, they will be released from the NICU near

their due date, and their development follows that of a baby

born on that date.

Kader

was born January 5, 2001, three months earlier than his original

due date of April 8. He went home from the NICU in May and is

now sixteen months old, but is developmentally on target for

his “adjusted age” of thirteen months: he’s cut

three teeth, babbles, and pulls himself up to stand.

“His

five-year-old sister has really helped to propel him on,”

says Kader’s home health care nurse, Janet Alston. “It

makes a big difference when there’s support in the home

from the family. I can say that from experience, because I work

with babies who don’t have that network of support and

it takes them longer.”

Kader

also receives periodic assessments at Emory’s Developmental

Progress Clinic, where evaluations are performed on babies who

have “graduated” from the NICUs to help doctors and

families gauge their therapeutic needs.

CREATING

THE OPTIMAL ENVIRONMENT

for the long-term health of premature infants is a priority

at Crawford Long Hospital’s NICU, which moved into new

quarters this summer, becoming part of a comprehensive birthing

center on the third floor of the recently completed Crawford

Long medical complex, across from the original hospital on Peachtree

Street.

The

unit, which has eight intensive care beds and sixteen intermediate

care beds, serves as a developmental lab where the latest research

is applied. Dim lights, muted sound, touch times (to ensure

the baby is not overstimulated,) and covered incubators all

play a role. But “teaching the mother how to relate to

her baby, to read its cues, to help the baby soothe and support

itself, this is the most important factor for the long-haul,”

says Ann Critz, an Emory neonatologist for twenty-two years

who developed the special care nurseries at Crawford Long.

The

tiniest babies cared for at Grady and Crawford Long are “micropremies,”

who weigh less than 1,500 grams (three pounds, five ounces)

and are between twenty-three and twenty-five weeks’ gestation.

Babies this young exist at the lowest limits of medicine’s

ability to save premature infants; just fifteen years ago, twenty-four-week-old

fetuses were considered miscarriages and no attempts were made

to save them.

By

all rights, micropremies should still be floating in the dark

confines of the womb. Their nervous systems are hypersensitive

and easily overwhelmed. Because their bodies do not have much

fat under the skin, they are unable to control their own temperatures

and become easily dehydrated. Their organs are fully formed,

but not necessarily functional. The blood vessels in their brain

are fragile and sometimes burst, requiring surgery, and the

mechanism that allows them to suck and swallow and breathe without

choking is not yet in place. Of the micropremies who do survive,

about half will have vision problems, many will have developmental

delays, and some face cerebral palsy and lung disease. For the

smallest and sickest of these babies, the decision must sometimes

be made to let them die, instead of continuing high-tech efforts

to prolong their lives

“There

are babies who are so very premature, it’s difficult to support

treatment. They are unlikely to survive and, if they do, they

have a high rate of serious complications,” says Cornish.

“We feel morally obligated to do everything that should be

done, but not necessarily everything that could be done.”

Cornish,

who received his medical degree from Johns Hopkins and did his

residency at Harvard, understands how emotional this decision

is for the parents: He has six children of his own, two of whom

spent time in NICUs, including his youngest, who has Down syndrome

and required open heart surgery as a baby. “When I talk

to the family of a high-risk baby, I tell them I’ve sat

on the other end of the discussion, and that I will include

them in every decision we make,” says Cornish.

If

families and doctors can’t agree on whether care should

be continued or withdrawn, a bioethics committee is consulted.

The committee, which includes doctors, nurses, hospital administrators,

social workers, and chaplains, makes a recommendation based

on what’s in the best interest of the child.

THE

EMPHASIS IN NEONATOLOGY

has switched from keeping ever younger, smaller neonates alive

to giving premature babies who do survive the best shot at healthy,

vital lives. “We seem to be butting up against the lower

limits,” Buchter says. “Now, we’re focusing on

better outcomes—nutrition, brain growth, lack of complications.

That’s the next major thrust.”

Emory

also has been involved in cutting-edge research, such as the

earliest clinical trials in the 1980s of different forms of

surfactant, a milky liquid that serves as a natural lubricant

in the lung. When surfactant, which is produced naturally in

full-term babies, is dripped into premature infants’ breathing

tubes, it helps to keep the air sacs of the lungs inflated.

“We

found that babies who had surfactant had higher survival rates,

a much shorter stay, decreased lung disease, and weren’t

on ventilators as long,” says Aimee Poor, Emory’s

neonatal nurse practitioner coordinator.

The

use of surfactant has cut deaths from respiratory distress syndrome

in half since 1990, the year it was approved by the Food and

Drug Administration. “The morbidity of being a pre-term

baby has really changed,” says Buchter, who did her own

neonatal residency in the mid-1980s when premature infants’

lungs frequently collapsed. “My residents today, very few

of them learn how to put a chest tube in, whereas it’s

something I did every night on call.”

Another

life-saving advance has been finding the right mixture of protein

and fats to feed premature infants through their IVs, which

is deposited directly into the baby’s bloodstream through

intravenous catheters the size of fishing line threaded into

arteries that aren’t much larger. Monitoring what goes

in—and what comes out—is crucial.

“You

have a patient who can’t talk to you or follow commands,”

Buchter says. “To me, the art comes in being able to sense

what’s going on through subtle changes. The more meticulous

you are with their care, the better. You have to calculate every

milligram of glucose given, every drop of urine produced. A

teaspoon of fluid is a huge amount to a one to two pound baby.”

In

the microcosm of gestation, something magical seems to occur

around the six-month threshold: Of infants born at twenty-three

weeks, 90 percent will die; of those born at twenty-six weeks,

90 percent will live.

At

this point, every ounce and every day can make a difference.

Pamela Brooks knows this first-hand: she spent the last two

days of her first pregnancy in the spring of 1993 upside down

in a hospital bed at Crawford Long, trying to keep her baby

inside for every additional hour possible.

“I

looked like a science experiment,” says Pam, who had already

taken steroid shots to help develop the baby’s lungs in

utero. “I was in total crisis mode when most women are

having their baby showers.”

Pam,

assistant director of corporate relations in institutional advancement

at Emory, and her husband, Richard, a real estate investor who

graduated from Emory College in 1989, knew her pregnancy was

high risk, since Pam had been diagnosed with fibroid tumors.

But they weren’t prepared for how tiny one-pound, eight-ounce

Kelsi Briana would be, born a full three months before Pam’s

due date.

“The

first time I saw her, she was an hour old in the incubator.

Her cry sounded like a kitten. With her legs curled up, she

was the length of my hand. It was such a shock, it all had a

surreal feeling,” Richard says. “But at my first word,

her eyes popped open. She knew her daddy.”

Kelsi’s

baby book opens with a photo of her hooked up to a ventilator,

above the handwritten caption: “I’m small but mighty.”

After three months in the Crawford Long NICU, under the care

of Ann Critz, she went home on her father’s birthday, Aug.

6.

Now

nine and in perfect health, Kelsi will enter fourth grade at

St. Thomas More in Decatur in the fall. She enjoys tennis, just

played a successful duet of “This Old Man” with her

mom at a piano recital, and loves math and science.

The

Brooks’s second child, Kayla, now seven, was also premature,

born one month early and weighing four pounds, four ounces.

She stayed in Crawford Long’s NICU for a month. “We

were eager to take her home,” Pam says. “She was bigger

than we were used to.”

Kelsi

and Kayla are looking forward to bike-riding and hula-hooping

over summer vacation at their Stone Mountain home. “I can’t

do the hula-hoop around my waist, but I can spin it on my arms,”

Kelsi says, demonstrating in her driveway.

And

as the hoops spin and her smile widens, the mighty Kelsi demonstrates

the full joy and wonder that can be hidden in an ordinary summer

afternoon.

|