|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The fire in Costa is still burning. And although Clarence Harrison was freed more than six months ago, the case continues to engage Costa almost daily.

In the months following Harrison’s release, Costa and Maxwell worked closely with Georgia State Represent-ative Stephanie Stuckey-Benfield to develop legislation that would allow Harrison to receive some financial compensation from the state for wrongful incarceration. This would not be the first time Georgia made such recompense; the state paid $500,000 in 2000 to former inmate Calvin Johnson, who spent sixteen years in prison before DNA tests cleared him of a rape conviction. The bill Costa helped to write would allot a standard sum to all future Georgia convicts who are exonerated, thereby having a lasting impact on the lives of GIP clients and others like them.

“A lot of states are moving toward legislation that would standardize all that,” Costa says. “For someone like Clarence, there should be a mechanism for him to get compensation for the time he lost.”

As president of the Emory Public Interest Committee (EPIC), Costa also is working to help public interest careers become more enticing for law students. The problem, he says, is that public interest jobs start at about $35,000 a year, not an attractive salary if you owe three times that amount in student loans. Big-firm jobs, by contrast, can start at $135,000.

But EPIC recently succeeded in establishing a loan repayment assistance program for graduates who choose public interest law: for every year they stay in it, EPIC will pay back a portion of their loans. Costa hopes such efforts will help make the option more palatable to other law students like himself.

“Emory law students are very excited about public interest work,” Maxwell says. “I get more applications from there than anywhere else. They have a real commitment to this kind of work. But law school can seem to be all about the big firms, so sometimes the students feel isolated. That’s why organizations like EPIC are so important.”

Costa’s efforts with the Innocence Project may have been unpaid, but they have not gone unnoticed. In January, Costa won Emory’s Humanitarian Award, given each year by the Division of Campus Life, for his work with the Innocence Project.

The triumph of Harrison’s release more or less cinched Costa’s decision to pursue public interest work after law school rather than joining a private firm.

“The public interest part of it is what was missing for me,” he says. “If I wanted to work for a big company, I would have stuck with computers.”

Maxwell thinks Costa will make an “outstanding” lawyer. “I can see him in the courtroom—he has a great personality for that, he’s very bright and quick on his feet,” she says. “He’s also great with clients. He’s already done the most exciting thing a lawyer can do in his career, and he’s not even a lawyer yet.”

Soon after Harrison’s release, Costa remembers, he was sitting in class at the law school, desperately trying to catch up on some reading he had missed while working on the case. Professor Frank Alexander walked up to his desk and Costa looked up, dreading a reprimand for slipping behind. Instead, Alexander shook his hand in congratulations.

“Jason is someone who combines an intense passion for law as a form of service with an excellent capacity for understanding the nuances of legal issues,” Alexander says. “And he wraps all that in a delightfully charming demeanor. I know he will have a profound impact wherever he goes.”

While Jason Costa’s law career is only beginning, Harrison is struggling just to make a life again, a little like Rip Van Winkle after many years of sleep. While he languished in prison, the world outside was changed by four presidential elections; by the rise of AIDS and the fall of the Berlin Wall; by Desert Storm and 9/11. Harrison missed the advent of the Internet and the proliferation of cell phones. He also missed nearly eighteen years of work.

“When you’re out [of prison], all the responsibility falls back on you,” he says. “It’s frustrating, not knowing how to do things, depending on others. Now I have responsibilities again. In prison I never had to worry about anything. I was told what to do all those years.”

But Costa and Maxwell have been scrambling to help Harrison put his world back together—an aspect of Innocence Project work where Maxwell wants the Georgia organization to shine. The challenge, Maxwell points out, has been that Harrison was freed so fast they had little time to prepare.

“In general, it takes six months to two years to get someone out of prison, so we thought we would have all this time to put plans in place,” Maxwell says. “But we got Clarence out a week later. So one remarkable thing that happened was, we had to get to know him and his family. Fortunately, he had fallen in love, and was able to go and live in his wife’s house. We were fortunate because Clarence is such a great guy.”

Maxwell and Costa helped Harrison find a seasonal job restocking shelves at Bas Bleu, a mail-order bookseller. They managed to have a computer with Internet access donated to him (“He couldn’t wait to start e-mailing,” Costa says), as well as a year of free computer classes through the New Horizons IT training company.

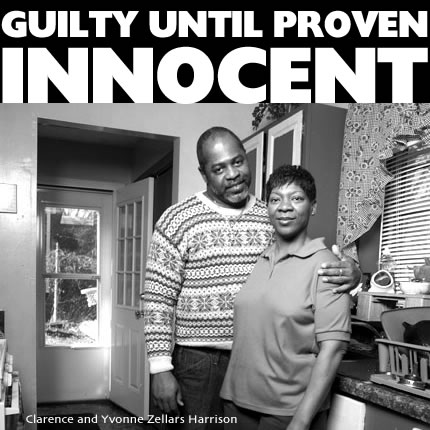

They also played a major role in helping Harrison and Yvonne plan their September wedding, for which they were able to get many of the nuptial trappings donated by local businesses. Costa and Maxwell were a groomsman and a bridesmaid.

“It was great being that involved,” Costa says. “We’ve been to family gatherings and everything—it was great.”

In the comfortable two-bedroom Marietta house that Yvonne and Clarence now share, wedding photos sit near pictures of Yvonne’s three daughters. On the wall of the bright green and yellow kitchen hangs a duck-shaped wooden plaque that says, “Welcome to the Harrisons’.”

Harrison’s favorite foods, according to Yvonne, are fried chicken, collard greens, and macaroni and cheese. He helps her with the dishes. (“I’d rather be back in prison,” he teases her.) But when he gets hungry, rather than just having a snack, he checks his watch to see if it’s mealtime—old habit from the prison routine.In the living room, decorated in dramatic red and black, Harrison’s new computer is set up beside the big screen TV. But his favorite spot is the smaller, brown-toned sitting room, where he retires to read his Bible. “It’s about the size of my cell,” he explains.

The two still attend church regularly, the Emanuel Church of God in Christ. “When [Clarence] gets into that Bible he is a totally different person,” Yvonne says. “His whole face just lights up.”

In just a few months, the couple has blended their lives. But Harrison’s past continued to take its toll on the present.

“We’re still adjusting to the reality,” Yvonne says. “I tell him, living in the population [of prisoners] messed you up. I like to have two or three people over at a time, he likes a house full. I used to live alone, so half the time if Clarence walks through the house, I jump.

“Sometimes,” Yvonne adds, “I pinch him and he says, ‘Why’d you do that?’ I say, ‘Just to make sure you’re really here.’”

Clarence receives letters every day from other prisoners, writing to congratulate him or seek his advice. He also has begun to speak to school groups and prison inmates about his experience. He tells them that even though he didn’t commit the crime for which he was convicted, his scarred record didn’t help any when he was arrested.

“What you do, it catches up with you,” he says.

As full and hopeful as Harrison’s life is now, nothing can make up for the years he lost. When he went to prison, he had children who were eight and two years old; now he has a grandchild who is two. His mother died while he was incarcerated.

He says he tries not to let bitterness get the best of him.

“I prefer to feel joyful,” he says. “Anger is something that will just hold you back. It’s a burden, that’s all anger is.”

In 2003, Harrison says, he spent Christmas in “the hole”—solitary confinement, a punishment for an altercation with anotherinmate.

This past Christmas he spent at home with Yvonne and at church. “The best thing is just being free, just being with my wife,” he says. “Yvonne was there for me, and she has been there since I’ve been out. She is still carrying me.”

During an interview just a couple of weeks before the holiday, Harrison pulled a folded sheet of yellow legal paper out of his pocket, a Christmas wish list from his grandchildren.

“I don’t even know what these mean,” he said, studying it. “I never got a chance to do much for my kids. I would spend Christmas with my grandkids, but I don’t want to go around with no presents. I don’t have money for presents.”

But then he brightened a little. “Maybe next year.” |

|

| |

©

2005 Emory University

|

|

|

|

|

|

|