When

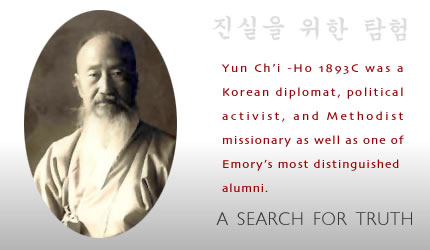

Ann Kim, an independent political fund raiser in Los Angeles,

decided to write a biography of Emory alumnus Yun Ch’i-Ho–a

Korean diplomat, political activist, and Christian missionary–she

had a personal incentive for learning more about his life: Yun

was her maternal great-grandfather.

“Our

whole family spoke of him,” says twenty-three-year-old

Kim. “We grew up hearing about how he had accomplished

so much and was such a pioneer and a Renaissance man, in terms

of all the languages he spoke, and that he had written the lyrics

to the Korean national anthem.”

She

also knew of Yun’s tempestuous relationship with the Korean

government, including time spent in jail and accusations that

he had been disloyal to his country by aligning himself with

Japan during Korea’s colonization.

“History

is so hard to sort out, it gets altered over time,” Kim

said. “I knew all these pieces of his life, but I wanted

to learn the truth.”

During

her research, Kim pulled from several of Yun’s writings,

including diary entries from the years 1891 to 1893, when he

was a student at Emory College in Oxford. He was especially

close to Warren A. Candler, then president of the University

and Yun’s sponsor.

“He

grew fond of his peers and professors, who often invited him

over to their homes for dinner, particularly Dr. Candler,”

says Kim. “This was the man that Yun later went on to name

one of his children after and to whom he entrusted his earnings

from missionary work in order to build a Methodist church in

Korea.”

When

Yun arrived in the United States in 1888, he was a twenty-four-year-old

political exile. His career in the Korean foreign service had

come to an abrupt end after friends of Yun’s who were radical

reformers staged a bloody but unsuccessful coup in Seoul. Although

Yun hadn’t taken part in the coup, many assumed him to

be guilty by association, and he left the country.

Emory

alumnus Young J. Allen 1858C, a Methodist missionary, had met

Yun in Shanghai, where he was a student at the Anglo-Chinese

College and, recognizing his abilities, arranged for him to

travel to America for study as a theology student–first

at Vanderbilt University, then at Emory.

An

Emory Magazine article written about Yun in 1976, “A

Korean at Oxford,” recounts Yun’s two years at the

University and captures the personality “of one of Emory’s

most remarkable alumni . . . a diplomat, educator, journalist,

patriot, and Christian statesman. Among the accomplishments

of this distinguished alumnus was to be a major role in founding

the Methodist Church in his native land, thus repaying abundantly

Emory College and its president, Warren Candler, for their faith

in the potential of a remarkable young man.”

In

diary entries from those years, Yun frets over algebra exams,

sloshes through mud and sleet to get to chapel, and eats grits

and biscuits with twenty-five boys at one table in Marvin Hall.

He grows close enough to the Candler family to write that:

Dr.

Candler is laboring under a debt of $700

. . . . Mrs. Candler told me that Dr. Candler is so much

in the habit of begging for the University that he often

cries out in sleep, ‘Who will give me $10 or $5?’ |

During

Yun’s summers in the United States, he toured rural Georgia

and Tennessee. Although sometimes taunted as a “Chinaman,”

he regularly visited churches of all denominations and in Nashville

taught Sunday School at the local prison. On campus, he was

an exemplary student and an active participant in clubs and

the baseball team. He felt guilt over enjoying these privileges,

as evidenced by this entry from November 6, 1892:

|

Here

I am, I am enjoying blessings that millions of my countrymen

know nothing of. I am in the light of pure religion, intellectual

freedom, political liberty. They are groping in the darkness

of superstition, ignorance, political slavery. Heaven

grant me the way to spread my measure of light among them!

|

After

graduation, Yun returned to Shanghai, where he was married.

In 1895, a change in government let Yun and his family return

to Korea, where he was appointed to the reform cabinet. He also

helped establish the mission of the Methodist Episcopal Church,

South, in Korea, and wrote the poem “Aegukka,” now

the words to the Korean national anthem. He became editor of

the Korean newspaper the Independent and led demonstrations

in front of the royal palace, angering conservative officials

and narrowly escaping assassination.

In

1899, he was moved to a port town as magistrate and remarried

after his wife died, fathering eight more children, among them

Kisun Yun, the famous concert pianist, and Jang Sun Yun, Ann

Kim’s grandfather.

Yun

returned to Seoul in 1904, becoming acting minister of foreign

affairs. After Japan established its protectorate over Korea

a few years later, he devoted his time to religious and educational

work. In 1908, Emory College awarded Yun an honorary doctorate.

Then, in 1911, Yun was one of more than a hundred men jailed

on suspicion of the murder of the Japanese governor-general

of Korea. Yun and five friends spent four years in prison. After

his release, he worked with the YMCA, which he established in

Korea, until his retirement in 1925. Less than four months after

Korea was freed from Japanese rule by the allied victory in

World War II, Yun died–on December 6, 1945.

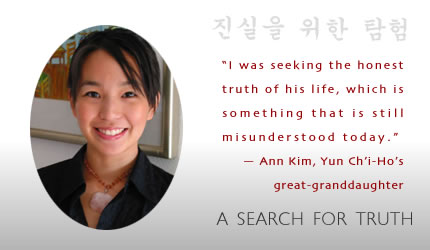

Kim,

who received her bachelor’s degree in political science

at UCLA, began reading everything she could find that had been

written by and about Yun, including his correspondence with

Candler, which is included in the Warren Candler papers at Woodruff

Library.

“I thought I’d do an independent research paper for

my own curiosity, working with [UCLA] Professor Namhee Lee,

who has been a mentor in my studies as well as my career,”

Kim says.

“Yun

Ch’i-Ho was always revered by our family members. He had

been born into the aristocracy, but did revolutionary work that

rebuked the government and corruption.”

Kim

was especially captivated by diary entries written when Yun

was in his twenties, near her own age. “A lot of the passages

spoke directly to situations in my life. As I was reading, I

kind of thought, he’s speaking to me. It was very meaningful,”

she says. “And his mastery of the language was so impressive–he

writes as if he were born here.”

The

more Kim read, the more she became convinced that Yun was indeed

courageous and loyal, and wanted only what he thought was best

for his country. “I tried to do my research being neutral

as much as possible. I went into it without a preconceived notion–if

you only have one perspective, you don’t get the whole

picture. But as I came across writings, they were really in

favor of Yun Ch’i-Ho and the work he had been doing. That

seemed to be a general consensus,” she said. “At first

he admired Japan, but not to the point that he wanted Korea

to be subdued to that country. His attitude changed as Japan

itself changed.”

Yun’s

time at Emory, Kim found, was “probably the most enlightening

that he had. When he was met with such warmth by Dr. Candler

. . . and he learned first-hand about the Western experience.

He was the second Korean to study in America. His conscience

was telling him he had to spread the missionary work to the

East. He felt he couldn’t conscientiously stay in the West,

but must return to work for the good of his fellow men.”

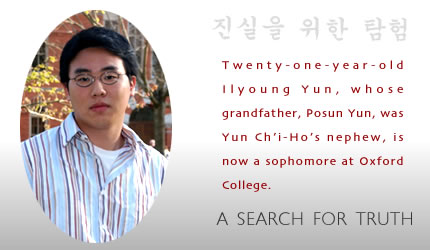

Another

young relative is also following in Yun’s path: Twenty-one-year-old

Ilyoung Yun, whose grandfather, Posun Yun, was Yun Ch’i-Ho’s

nephew, is now a sophomore at Oxford College of Emory.

“One

reason [I came to Oxford] was that I knew Yun Ch’i-Ho had

attended here,” says Yun, who plans to proceed to Emory

College next year and major in economics. “Another is that

my father was friends with [former Emory president] Dr. James

Laney when he was ambassador of South Korea.”

Ilyoung

Yun was born in California but has lived for most of his life

in Seoul. When he came to Oxford, he discovered what his great-great-uncle

had found more than a hundred years ago: “Here, community

is very important. It’s easy to make friends.”

Kim

is herself interested in Korean politics, especially the North

Korea-South Korea divide and the talks occurring in China.

She completed “Yun Ch’i-Ho: A short biography,”

which places Yun’s life in the context of Korean history,

in February 2003 and is hoping it will be published.

“I was seeking the honest truth of his life, which is something

that is still misunderstood today,” she says. “For

his great-granddaughter to go out and do her own research, and

to come to the conclusion that he was hard-working and honest

in all his endeavors–I think he would be proud. This is

something I had always heard from my family, but I wanted to

find out for myself.”

|

|