“My

dear child! Is it possible that you have never seen or read

of the wheel?”

“The

wheel? What wheel?”

“The

bicycle then—the machine on wheels, that goes faster

than the horse.”

“Ah,

bah! I have heard of people who put the cart before the horse,

and so you are one of them. I shall like to see the wheels

go ahead of—faster than the horse, sir!” Vic laughs

mockingly.

It

takes the lieutenant some time to explain to this untutored

mind the mechanism of the bicycle, and when at last she seems

to comprehend she can talk of nothing else.

“How

perfectly splendid!” she cries. “It must be next

to flying. . . .”

—Lawrence

L. Lynch, Under Fate’s Wheel: A story of mystery,

love, and the bicycle, (Ward, Lock, and Bowden, 1900).

In

the late nineteenth century, women could often be found sitting

primly around the house in whalebone corsets, determined that

their waist size not exceed their age at marriage. In

the late nineteenth century, women could often be found sitting

primly around the house in whalebone corsets, determined that

their waist size not exceed their age at marriage.

When

the bicycle came on the scene in the 1880s, it was a liberating

vehicle for women, who were suddenly encouraged to get more

fresh air and exercise. And so they put on their bloomers, hiked

up their skirts, and gamely pedaled away, as is recounted in

a cluster of “bicycle stories” in magazines and popular

women’s literature of that era.

“These

are stories about freedom, getting out and seeing things, having

adventures,” says Associate Professor of English Catherine

Nickerson, who discovered the stories while serving as a consultant

on an Emory Women Writers Resource Project on novels written

by women near the turn of the twentieth century.

Then

came bicycle backlash.

“Conservatives

were afraid women who bicycled would fall in with the wrong

crowd, make themselves vulnerable by being so far away from

the house, and might even be raped,” Nickerson says.

Books

like Under Fate’s Wheel (1900), a romance-mystery

by Lawrence L. Lynch—the pseudonym of Emma Murdoch Van

Deventer—reflect this ambiguity by glorifying the new-fangled

vehicle even while including cautionary warnings against it.

“You

must know the Bike has struck the town, not numerously, but

with fervour,” writes older brother in a letter. “Do

you ride a bike, Sis? If you haven’t, don’t. I’ve

ridden bucking broncos, kicking mules, trotters, and—rails,

and the bike can make you ridiculous in more languages, sore

in more places, and dismount you quicker than any animal that

lives. . . . I have ridden the two-wheeled, evilly disposed

demon for the first and last time!”

From

bicycling to suffrage, women’s issues of the day were reflected

in the popular literature, both in hardbound novels and paperbacks

(also called dime novels and “yellowbacks.”) The most

common genres were mystery, crime, and detective novels; wilderness

adventures and Westerns; and tales of suspense, seduction, and

romance.

The

Emory Women Writers Resource Project, in collaboration with

the Victorian Women Writers Project at the University of Indiana,

has been awarded a grant of $314,000 from the National Endowment

for the Humanities (NEH) to create an online database of about

330 of these American and British detective, crime, and romance

novels, authored by women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries.

The

database fits in well with the mission of the Women Writers

Resource Project, which began in 1995 to enable students to

create electronic editions of early literary works by women.

The project includes significant texts written by early African-American,

native American, abolitionist, and suffragette women, says Masse-Martin/NEH

Distinguished Teaching Professor of English Sheila T. Cavanagh

(below), the project’s director.

“Students

and scholars from around the world now visit the site to access

material ranging from World War I poetry to the anonymous Memoir

of Elizabeth Jones, A Little Indian Girl,” she says. “Students

and scholars from around the world now visit the site to access

material ranging from World War I poetry to the anonymous Memoir

of Elizabeth Jones, A Little Indian Girl,” she says.

The

Robert W. Woodruff Library already had an impressive collection

of yellowbacks and dime novels, thanks to a few staff visionaries

who realized such novels would someday be rare as well as valued.

In

1960, librarian Marella Walker and Professor of English Harry

Rusche began a serious effort to collect yellowbacks. Ten years

later, Walker arranged to buy the Harold Mortlake Collection

of detective fiction. And in 1996, Emory received the Hugh Greene

Collection (1900 to 1914) and the Graham Greene-Dorothy Glover

Collection of Victorian Detective Fiction (1846 to 1900). In

total, the library has more than eight hundred American and

British yellowbacks.

“The

texts that we will be digitizing are hard for researchers to

find readily,” Cavanagh says. “By placing these novels

on the Web, we are making one of the strengths of our library

more visible while reducing potential wear on the books.”

Being

victims of their own success, many dime novels and yellowbacks

are fragile or in poor repair. In London, readers could rent

a yellowback at one train station and return it at another.

“The cheapness of their medium—a feature that increased

their popularity—facilitates their destruction,” Cavanagh

says. “Many of these texts face imminent extinction.”

Novels

to be included in the database span the decades from the Civil

War to World War I and are set against a backdrop of struggles

over slavery, women’s suffrage, labor unions, urbanization

and industrialization, and changing roles between men and women.

The

database will create a “portal” for research that

allows scholars more efficient ways of analyzing the texts.

“For example, if you want to see how many mentions are

made of Paris, you would just do a search, rather than flipping

through a thousand books,” says Cavanagh.

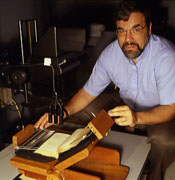

Assisting

on the project are the Woodruff Library’s Lewis H. Beck

Center for Electronic Collections and Services and the library’s

preservation and special collections staff. “One of the

reasons we got the grant was that we were committed to preserving

the original books,” says Charles D. Spornick (left), coordinator

of the Beck Center. Assisting

on the project are the Woodruff Library’s Lewis H. Beck

Center for Electronic Collections and Services and the library’s

preservation and special collections staff. “One of the

reasons we got the grant was that we were committed to preserving

the original books,” says Charles D. Spornick (left), coordinator

of the Beck Center.

Novels

that have been selected by the project’s editorial board

are converted to electronic data through a painstaking process.

First, they are placed in an elaborate wooden cradle with plexiglass

arms while they are photographed cover to cover (including inserts,

advertisements, and illustrations) with a $40,000, twelve-megapixel

digital camera. After the high-resolution images are converted

to text using Optical Character Recognition software, proofreading

and encoding typically takes an additional twenty hours p er

novel. er

novel.

Nickerson

(right), for one, can’t wait for the database to be up

and accessible. “I believe popular literature is vastly

under-examined by academics,” she says, “although

there has been a real change in this over the last fifteen years,

with a good body of scholarship emerging on women’s popular

writings, all endeavoring to understand how women articulated

their experiences and lives at the time.”

Like

fiction by Danielle Steel or Mary Higgins Clark today, these

mass-produced novels were considered escapism as opposed to

great literature.

“They

were enormously popular and paid the usual price of this popularity:

to be regarded with suspicion by many stern moralists and to

be sneered at by the supercilious type of critic,” says

Edmund Pearson in Dime Novels: Following an Old Trail in

Popular Literature. “These were to be tales of dread

suspense; of the calm before the storm, but rather more of the

storm than of the calm. In their pages, . . . tons of gunpowder

was to be burned, human blood was to flow in rivers, and the

list of dead men was to mount to the sky.”

Despite

their themes of murder and mayhem, many of the action-packed

novels that swept the country from the 1860s through the 1920s

were written by women—women writing under their married

name, their maiden name, their initials, male pseudonyms, a

“stable” of authors all writing under one name, or

one woman writing under different pseudonyms.

“It

really changes the impression that women’s writing was

all flowery and pretty,” says Nickerson. “There was

a lot of violence.”

Take

this graphic passage from Beatrice Heron-Maxwell’s The

Adventures of a Lady Pearl-Broker (New Century Press, 1899):

Horror.

A woman was lying on the floor, her distorted purple face

bruised and bleeding, her eyes staring upward in mute and

desperate appeal. The lace ruffle around her neck at which

one of her hands was clutching convulsively, had been twisted

and strained with such force, that it looked like a narrow

ragged string on either side of which the flesh rose in two

dark ridges.

Just

below the roiling surface of the narratives, however, ran strong

undercurrents of social commentary.

“These

works were maligned because of their melodrama, their purple

prose, their plot-driven narratives. It’s not Proust,”

says Nickerson. “But why were these novels popular? Because

they struck a nerve. Women were right in the center of defining

what the issues of the day were, both in the U.S. and Britain.

This is a really valuable legacy of women’s writing.”

“What’s

your ideal?” demanded Patience.

“Ideal?

What ideal?”

“Why,

of man, of course.”

“Oh,

man! I haven’t thought much about men. I don’t read

novels, like you do.”

—Patience

Sparhawk and Her Times, by Gertrude Atherton (John Lane, 1897).

It

may seem ironic that novels considered “morally suspect”

in their day and ignored by scholars for so long are now the

focus of such intense academic scrutiny. Even the titles seemed

to discourage serious scholarly discourse: Two Girls and

a Dream, The Devil’s Motor, At the Foot of the Rainbow,

A Woman’s Love Lesson.

“People

wanted something that would grab their attention and keep them

from being bored,” says Nickerson. “These would be

the equivalent of airplane reads today.”

The

stories were populated by orphaned young women with spunk, handsome

Yankee ranchers, mistresses of wealthy men, New York women of

fashion, well-known actresses, high-tempered queens of gambling

houses, dashing naval officers, spinster aunts, insistent suitors,

randy dukes, and haughty duchesses.

“With

this kind of fiction there’s a lot of interest in engaging

the reader with the characters,” says Cavanagh. “Writers

were far less concerned with realism than with whetting the

reader’s appetite for more.”

A

wry sense of humor is apparent in many of the works as they

capture the lofty and occasionally contradictory demands made

of women of the time, while allowing them to transcend gender

barriers by taking on professions and roles usually occupied

by men.

“The

question people frequently ask me, and other scholars of women’s

popular novels, is ‘Are they any good?’ ” says

Nickerson. “I can only answer that I personally find these

novels satisfyingly complex . . . [and] sometimes hilarious

in their feminist wit.”

As

Nickerson states in her scholarly work The Web of Inequity:

Early Detective Fiction by Women (1998), women writing around

the turn of the twentieth century “formulated a style .

. . that drew on the moral force of the domestic novel and the

symbolic language of the gothic mode to critique the gender

and class politics of maturing capitalism.”

These

best-selling novels, she writes, featured women learning about

“corruption and transgression, looking below the placid

surface of things, and questioning appearances.”

Such

invisible machinations are apparent in titles such as The

Unseen Hand, Out from the Night, and Between the Lines.

Investigations and inquiries often take place in the domestic

sphere, signifying the centrality of home and family, but give

insight into the broader, male-dominated worlds of work and

governance.

Detective

and crime stories offer a great deal of information about people’s

fears and anxieties, threats to the social order, and proposed

or hoped-for solutions to these problems.

Sometimes

these fears take form as a “haunted” house, complete

with phantom screams, creaking doors, and ghostly intruders.

This device was used in The Mayor’s Wife (1907)

by Anna Katharine Green, a best-selling and prolific author

who wrote more than sixty detective novels. In it, the lady

of the house has been taken over by a mysterious illness after

seeing an apparition in the library:

“I

was sitting reading . . . oh, I can not think of it without

a shudder!—the page before me seemed to recede and the

words fade away in a blue mist; glancing up, I beheld the

outline of a form between me and the lamp . . . I was conscious

of no substance, and the eyes which met mine from that shadowy,

blood-curdling Something were those of the grave. . . . As

it burned into and through me, everything which had given

reality to my life faded and seemed as far away and unsubstantial

as a dream.”

In

fact, the “ghost” has been manufactured by the mayor’s

wife, who—in a plotline that rivals any contemporary soap

opera—has discovered that her abusive first husband is

not dead, as she thought, but is alive and working for her current

husband, the mayor. The fictional haunting becomes a metaphor

for a personal attachment she can’t escape.

Women,

cast as heroines and villains, investigators and victims, are

“central to these explorations of evil, morality, and justice,”

says Nickerson.

The

genre captures the transition from Victorian to modern times,

as the fairer sex began “asserting themselves politically,

socially, legally, emotionally, and artistically,” she

says. “Over the nineteenth century, the idea of what a

woman was got redefined.”

Indeed,

contemporary women may discover they owe much to the fearless

young girl in Lynch’s novel who “set the wheels of

Fate in motion by running away from home to be a bicycle rider.”

For

more information about the Emory Women Writers Resource Project,

go to http://chaucer.library.emory.edu/wwrp/.

To find out more about the Lewis H. Beck Center for Electronic

Collections and Services, go to http://chaucer.library.emory.edu/.

|