|

BY

MARY J. LOFTUS

Norris

Lake, about twenty miles east of Atlanta, is the first scheduled

pit stop for twenty riders taking part in this year’s ActionCycling

200. Each May, the riders pedal from Atlanta to Athens and back

again to raise money for AIDS vaccine research at Emory.

“The

butterflies, we call ’em,” says a local, who is manning

a table for the Norris Lake Neighborhood Association. “They

come flocking through here every spring in red, yellow, and

green.”

Harriet

Robinson, Asa Griggs Candler Professor and chief of Emory’s

Division of Microbiology and Immunology, has come out this Saturday

morning to cheer on the riders. She stands in the Phillips gas

station parking lot, eagerly scanning the horizon.

“Here

they are!” she says, spotting the front-runners in their

Day-Glo orange biking jerseys, helmets, and padded black shorts.

The first arrivals pull into the lot just after 9 a.m. and descend

on the support van to grab Powerade, pretzels, apples, candy

bars, and bananas.

Robinson,

dressed casually in a sleeveless white top and blue slacks,

circulates among them, joking and making conversation. She is

accompanied by her four-year-old grandson, Jack, who is visiting

from Pittsburgh with his parents and younger brother, Gus. Robinson,

dressed casually in a sleeveless white top and blue slacks,

circulates among them, joking and making conversation. She is

accompanied by her four-year-old grandson, Jack, who is visiting

from Pittsburgh with his parents and younger brother, Gus.

“Do

you want to finish the ride instead of me?” a rider asks

Jack, noticing him admiring the sleek racing bikes.

The

group’s de facto leader, John Beal, organized Action Cycling

of Atlanta (motto: “pedaling for a purpose”) and has

ridden in races in Alaska, Canada, and across Montana that raised

millions of dollars for AIDS research.

“Basically,

a bunch of Atlanta riders did a European ride a few years ago,

and so little of the money went to where it was supposed to

that we resolved to start a ride here and make sure the money

went to the right place,” Beal says. The group raised $65,000

for the Vaccine Research Center last year and an additional

$20,000 so far this year.

Robinson

is a celebrity of sorts to this group. “Most of the bikers

know Harriet,” Beal says. “She’s the scientist

from Emory who has an AIDS vaccine in clinical trials. She came

to Athens last year and talked to us. She’s probably not

as well known as she will be one day.”

By

9:30 a.m., almost all the cyclists have checked in, reenergized,

and are ready to start out for Walnut Grove, the next stop.

Two riders, though, haven’t shown up yet. A few minutes

later, they pull in together– Michele Hennessy, who went

an extra four miles after missing a turn-off sign, and Joy Martin,

who looks flushed but elated.

“I’ve

never ridden this far in my life,” Martin announces.

“Well,

I tell you, you are courageous,” Robinson replies.

The

same may well be said of the sixty-six-year-old Robinson, a

top researcher at Emory’s Vaccine Research Center who–through

sheer tenacity and despite a number of obstacles that might

have discouraged those with less gumption–has developed

one of the most promising AIDS vaccines in clinical trials today.

For

much of her career, Robinson was a single mother of three boys,

the sole woman in a roomful of male scientists (“They would

call the men ‘Dr. so-and-so,’ and I would just be

‘Harriet,’ ”) and an independent thinker who

often fell outside of the scientific mainstream.

Her

early successes in using DNA to create vaccines were met with

skepticism–professional journals wouldn’t publish

her results and her grant proposals were routinely refused.

“You don’t think this will ever be useful, do you?”

read one reviewer’s comment.

Still,

Robinson has taken her groundbreaking DNA-based AIDS vaccine

from the lab through successful primate trials and into human

testing–even when she’s had to brave machine-gun fire

during rebel insurrections to do so.

“I

believe our vaccine has real potential,” Robinson says.

“There is a subset of the research community that is discouraged.

They criticize us for being overly optimistic. But the fact

remains that our vaccine works in monkeys.”

After

years of combatting the naysayers, Robinson’s life runs

fairly smoothly these days–her research is well funded,

she is highly regarded as a scientist, and she lives quietly

in a modest brick ranch on a wooded lot near the Emory campus,

a short drive from her lab at the Yerkes National Primate Research

Center.

“We

used to walk our dogs together in the mornings,” says Tom

Insel, former director of Yerkes who is now head of the National

Institute of Mental Health, “and the great thing about

Harriet is that she was always thinking about science–how

to get the next project completed, what the most recent results

might mean, where to get the best advice. Her concerns were

never about personal gain or recognition. I have never known

a scientist with so much talent and so little ego.”

The

virus Robinson is squaring off against is the most lethal infectious

disease in the world: AIDS has killed twenty-two million people

globally since 1981, and forty million are currently infected.

In the United States, more than one million have the virus; in

China and India, more than ten million are infected in each country,

as are an estimated 30 to 60 percent of the sub-Saharan population

in Africa.

And

the spread continues. Almost five million people were infected

last year, the largest number of new cases since AIDS was discovered,

and three million died. Young people fifteen to twenty-four

years old account for nearly half of all new infections worldwide.

Sixty-eight million people are projected to die from AIDS by

2020–more than the entire population of Great Britain.

The

scientist who develops an affordable, effective AIDS vaccine

will save more lives than have ever before been spared by a

single medical innovation save, perhaps, the discovery of penicillin.

“AIDS

is an extraordinary kind of crisis; it is both an emergency

and a long-term development issue,” states the 2004 United

Nations AIDS Report on the global epidemic. “Despite increased

funding, political commitment, and progress in expanding access

to HIV treatment, the AIDS epidemic continues to outpace the

global response. No region of the world has been spared. The

epidemic remains extremely dynamic, growing and changing character

as the virus exploits new opportunities for transmission.”

By

now, the devastatingly effective strategy of the AIDS virus

is well known: the virus invades the human immune system, targeting

helper T-cells and macrophages–the very white blood cells

sent to destroy it. Opportunistic infections and cancers that

the body could normally fight off quite easily ravage people

with AIDS, once their immune systems start shutting down.

No

successful treatment for AIDS existed until 1987, when the first

antiretroviral drug was discovered. Antiretrovirals, which work

by slowing the reproduction of the virus, are now given in combinations

(anti-HIV “cocktails”) that can reduce death rates

by more than 80 percent.

But

such drug regimes, which must be taken consistently and for

life, are expensive–from $12,000 to $45,000 a year per

person–and the vast majority of those with the virus live

in developing countries where such costly treatments are not

an option.

Researchers

also worry that widespread misuse of anti-HIV drugs by patients

who take them only sporadically, compounded by haphazard manufacturing

practices in labs that don’t meet rigorous standards, could

spawn future epidemics of drug-resistant strains of the virus.

“The

real solution for the world,” says Robinson, “is a

vaccine.”

Vaccines

prime the immune system to recognize disease-causing organisms–similar

to providing a mug shot (“Look out for this guy, he’s

dangerous”) so that the body’s defenses will spring

into action when they encounter the virus.

The

impact of vaccines on public health over the last century has

been substantial: smallpox has been eradicated, polio has been

greatly reduced, and cases of measles and Hib (haemophilus influenzae

type b, at one time the leading cause of childhood bacterial

meningitis and mental retardation) are at a record low.

But

developing a vaccine for AIDS is especially difficult, says

Rafi Ahmed, director of Emory’s Vaccine Research Center,

because the virus is constantly changing and mutating. “HIV

presents a moving target, essentially,” says Ahmed. “You

have to understand both the virus and the immune system to develop

an effective vaccine.”

Traditional

vaccines are made from the virus itself, which has been killed

or weakened. The danger is that such a vaccine, if not properly

inactivated, might actually induce the illness; the original

version of Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine caused two hundred

and sixty cases of the disease, resulting in ten deaths.

But

Robinson’s vaccine, developed in collaboration with the

National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC), is unique in that it is a DNA-based

vaccine–a technique Robinson pioneered. DNA vaccines stimulate

an immune response by using only pieces of the virus instead

of the virus itself, so the recipient is never placed at risk

of infection.

Robinson’s

AIDS vaccine requires three shots: a DNA-based inoculation to

prime the immune system, followed by two poxvirus booster shots,

which increase the body’s immune response. “The DNA

vaccine establishes the breadth of the immune response,”

she says, “while the poxvirus boosters affect the height

of the response. The result is that the combination is more

effective than either one alone.”

Robinson

chose poxvirus, a version of the virus first used as a smallpox

vaccine, for the booster because it was large enough to carry

several extra HIV genes.

“The

pox viruses are enormous,” she says. “They are like

the Battleship Galactica of viruses.”

Robinson’s

vaccine has tested well in trials with rhesus macaque monkeys

at Yerkes. Twenty-three of twenty-four monkeys given the DNA

vaccine and poxvirus booster failed to develop AIDS symptoms

even after exposure to high levels of the virus. In the control

group, five of six non-vaccinated monkeys died of AIDS within

six months of being infected with the virus.

“To

our knowledge, no other HIV vaccine or large-size trial, has

reported such a high level of protection for such a long period

of time,” Robinson says.

The

vaccine has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration

for human trials, which began in January of 2003. HIV-negative

volunteers were randomly assigned to receive one of the following:

high-dose vaccine, low-dose vaccine, or placebo.

“We’ve

had the DNA vaccine in clinical trials for a year and a half

at three different sites–Seattle, San Francisco, and Birmingham–in

thirty people,” Robinson says. “These trials have

been very successful in showing that the vaccine is safe for

humans.”

The

next series of human trials is scheduled for early 2005 to determine

the safety of the DNA prime combined with the poxvirus booster,

and to establish a dosing schedule. After this, a third series

of trials will be conducted in a population at high risk for

acquiring AIDS, with some volunteers receiving the vaccine and

others receiving a placebo, to gauge effectiveness.

Robinson

believes a usable AIDS vaccine is still five to seven years

away but, she adds, “I have great hopes.”

Giving

up isn’t in Robinson’s lexicon, says Helen Drake-Perrow,

her office manager of seven years. “She inherited from

her parents a sense of ‘can do’–working things

out for herself instead of relying on others. She is independent,

has clear logic, and is full of confidence, yet is still humble.”

Harriet

Latham Robinson was reared in Boston, the only girl among three

brothers. She remembers her mechanical engineer father, Allen

“Jack” Latham, tinkering in the basement with his

inventions. He was later named New England inventor of the year

for creating a disposable centrifuge to separate blood.

Her

mother, Ruth Latham, earned a master’s degree in chemistry

from Oberlin and taught organic chemistry at Smith College before

staying home to raise a family.

“She

would say sodium bicarbonate for baking soda, or H2O for water,”

Robinson recalls. “We were always doing interesting things.

As kids, we made tents and spent a lot of time outdoors. We

had an enormous garden. I think we were the last family in the

city of Boston to keep chickens.”

Despite

her mother telling her “an educated woman can never be

happy,” Robinson became a scientist–and an academic.

“I went to Swarthmore intending to major in history,”

she said, “but I became fascinated by the development of

organisms.” She went on to attend MIT, where she earned

a master’s degree in molecular biology and a Ph.D. in microbiology.

Receiving

her doctorate in 1965, a time when just 8 percent of science

Ph.D. graduates were women, didn’t faze Robinson. She loved

being one of the new recruits in the fledgling molecular biology

department at MIT and thrived on the synergistic environment

of the lab.

She

won a postdoctoral fellowship in the virus laboratory at the

University of California at Berkeley, where she met her husband,

William Robinson, who was also a scientist. They had three sons.

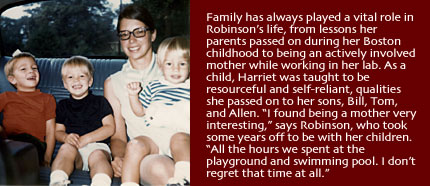

“I

basically became a full-time mother,” she says. “I

worked two mornings a week in a lab, but I found being a mother

very interesting. Some of my very best friends are from that

part of my life–all the hours we spent at the playground

and the swimming pool. I don’t regret that time at all.”

When

her sons were five, six, and seven, Robinson went through a

divorce and became a single mother.

“I

tried to get a job in California, but no one would hire me as

faculty or a technician,” she says. “So I looked all

over the country, and ended up back in Massachusetts, at the

Worcester Foundation [for Experimental Biology.] I had a lab,

and they had their new scientist.”

Robinson

stayed at the Worcester Foundation–famous as the lab where

“The Pill” was developed–for ten years. Her research

on viral-induced cancers led to the identification of host genes

that can be mutated by viruses into cancer-inducing genes. Robinson

also discovered that an immune response could be triggered if

viral DNA was injected into chickens.

“Harriet

became enchanted with the idea of using DNA itself as an immunizing

agent,” says Thoru Pedersen, professor of biochemistry

and molecular pharmacology at the University of Massachusetts

Medical School, who was Robinson’s colleague of many years

at the Worcester Foundation. “Harriet has absolutely fearless

courage to pursue new ideas. She’s willing to try things

off the beaten path, and through this, she has become quite

famous in the field of virology.”

While

Robinson worked nine to five, a live-in housekeeper managed

the homefront. But Robinson put in plenty of parenting time

herself. Colleagues remember that her license plate spelled

out, “HEY MOM.”

After

her sons left home one after the other to attend Stanford University,

where their father was a professor, Robinson began working more

hours in the lab. “I had the worst case of empty nest syndrome,”

she says.

In

1988, she was recruited to a research position in the pathology

department at the University of Massachusetts.

“Harriet

was working on a type of molecular pathology that was technically

very advanced, but conceptually very simple: since vaccine production

is essentially a matter of protein synthesis, the fastest way

to generate the specific protein is to teach the cell how to

make it by providing it with specific, ready-made DNA,”

says Guido Majno, then chair of the pathology department. “It

seemed so obvious and promising, why had it not been done before?”

Robinson

began developing a simian version of the AIDS vaccine. The thinking

in the scientific community at the time, though, was that DNA

vaccines would never work because the DNA would not be taken

up by enough cells to produce an immune response.

“No

journals would publish my results. My grants kept getting turned

down. My department chair actually used department funds to

keep me going at a critical point. But I didn’t abandon

it,” she says. “I always thought it would come through,

because the lab results were so good.”

By

1992, more scientists were working on DNA vaccines, which had

become more widely acceptable; Robinson’s results were

published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

and in the journal Vaccine.

Now

Robinson was able to turn her attention more fully to developing

a human AIDS vaccine. The complexity of the virus itself fascinated

her: the way it killed the helper T-cells of the immune system,

its resistance to containment.

“If you vaccinate but you don’t protect the helper

cells, you’ve lost your supply lines.” she says. “It’s

like Napoleon’s army in Moscow after winter comes.”

Drawn

by the breeding colony of rhesus monkeys at Yerkes National Primate

Research Center–one of eight national primate research centers

funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)–Robinson

came to Emory in 1997 as chief of microbiology and immunology.

She joined a cadre of internationally known researchers working

on vaccines for diseases including malaria, herpes, hepatitis

C, and influenza.

“The

closest I’ve come to the MIT environment is the Vaccine

Research Center here,” says Robinson, “just in the

confluence of people and the excitement about what’s going

on.”

The

Vaccine Research Center at Yerkes was the perfect fit for another

reason as well: Developing an AIDS vaccine is the center’s

primary goal.

“Harriet

had a different strategy for approaching vaccine development,”

says Insel, the former director of Yerkes who recruited Robinson.

“All of the major companies had shut down their AIDS vaccine

programs and moved to developing retroviral drugs, so she was

already a bit of a maverick for committing to a vaccine. Her

DNA approach, which was revolutionary at that time, was really

intriguing because it represented a new way of thinking about

vaccines. DNA is heat stable, so if the vaccine was effective

it could be used in Africa or Asia without refrigeration–an

obvious plus for global health.”

In

2001, results from Robinson’s monkey trials were published

in the journal Science, with Yerkes Assistant Research Professor

Rama Amara as lead author. It became the most cited paper in

immunology for several months, and Robinson joined the elite

group of researchers at the front of the AIDS vaccine race.

Make

no mistake–for these scientists, this is the Tour de France,

and they want to win. There is cooperation, but there is quite

a bit of competition as well. Once a vaccine is available, the

demand will be abundant: market estimates are between four billion

to ten billion dollars per year.

Merck,

Chiron, Aventis-Pasteur, Glaxo-Smith Kline and the NIH Vaccine

Center are all working on AIDS vaccines, as are several other

universities, including Oxford, Yale, and the University of

North Carolina.

“In

a sense, the competition has been consciously generated by funding

agencies and the NIH,” says Neal Nathanson, vice provost

for research at the University of Pennsylvania and former director

of the Office of AIDS Research at NIH. “They put out enough

money to bring into the field anyone who has a credible idea.”

Robinson

believes that in the end, there may be more than one AIDS vaccine,

just as there is more than one polio vaccine. “Typically,

after a vaccine is developed in a lab, it is handed over to

a large pharmaceutical company for commercialization,”

she says. “But I really want to retain control through

the efficacy trials.”

These

days, work in the lab and with the monkeys is handled by lab assistants,

vet techs, and animal techs, rather than Robinson, who concentrates

on writing grant proposals and dealing with government regulations–the

frustrating logistics of birthing a vaccine.

Still,

her reserves of courage and tenacity are sometimes called upon.

In

the fall of 2002, Robinson flew to the Ivory Coast for a series

of meetings organized by the CDC and the health ministry about

testing a version of her vaccine in Africa. The plan was to

establish a vaccine clinic in Abdijan, the capital city.

At

her hotel, she awoke in the middle of the night to a sound like

a truck running into a wall and scattered machine-gun fire.

“I just stayed in bed through the whole thing,” she

says.

“I

don’t think any of us had any idea how bad it was,”

says Jeff Lennox, an Emory professor of infectious diseases

and director of the Ponce AIDS clinic, who was also in Abdijan

for the meeting. “When we got up the next morning, the

door to the hotel was shot out. We were told to stay inside.

You could see buildings burning, but there were no vehicles

moving outside. It was totally quiet.”

The

team was trapped in the hotel for two days. “Harriet was

great,” Lennox says. “Some people were very stressed

out, but she was very calm.”

They

were finally hustled into a van and taken to the airport, where

an Air France 747 touched down long enough to fill with Americans,

embassy workers, and airline staff. It was the one plane allowed

to leave the city.

“Harriet

was mostly upset that so much planning and organizing had gone

into this multi-country effort to have HIV trials in Africa,

and it wasn’t going to happen,” Lennox said.

Robinson

admits it was a great disappointment. “It was the perfect

place to do a trial. We lost so much to political instability,

it’s just tragic.”

But

the Ivory Coast setback seems only to have increased Robinson’s

determination to see her vaccine through to production and distribution.

Her team is now getting two vaccines ready for developing countries–one

for Africa and one for India–so that at least one will

make it through testing.

“We

still have very hard work ahead,” she says. “A lot

of critical junctures. We only go down in AIDS history if we

make it across the finish line.”

|