|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It’s

dinnertime at the Sigma Chi house, and the noise level is rising

as the brothers line up, cafeteria-style, to fill their Styrofoam

plates. The dining room is rather spare, with long folding tables

and metal chairs, and the cutlery is plastic; but there are

steaming pans of ham, barbecue, sweet potatoes, and mixed vegetables.

Just like Mom used to make.

“I’d

say dinner is, like, a pretty important time of day for us,”

says senior Jeffrey Borenstein, between bites, surveying the

rapidly filling room. Behind him, there’s a sudden crash

that makes Borenstein jump; one of his fraternity brothers has,

inexplicably, attempted to leap over a chair, and didn’t

quite clear it.

Dinner

with the Sigma Chis is very casual, even a little chaotic. It’s

a warm March day, and most of them are wearing shorts, T-shirts,

and flip-flops. Several have wet hair, fresh from the shower

or gym. They jostle, shove, and talk over one another until

they’re almost yelling; inside jokes and offhand insults

fly thick. But it’s clear this is a time they look forward

to, a time to congregate and talk over the events of the day,

and to make plans for the night.

About

half of the sixty Sigma Chis, away from home for the first time

as college students, live here in the house. Across from fraternity

president David Politis, Jacques Edeline, a sophomore with an

impish grin and wild, bushy hair that sticks up all over his

head, takes a seat. He has a plate stacked with four pieces

of white bread and good-sized mounds of peanut butter and jelly,

presumably to fortify him for tonight’s chapter meeting.

Is that his dinner?

“No,

I had some ham and vegetables already,” he says. “This

is just . . . my after-dinner snack.”

On

a campus as sprawling, diverse, academically challenging, and

potentially impersonal as Emory, joining a fraternity or sorority

can provide students with a sense of community that helps keep

them grounded. Some twenty-five percent of Emory’s six-thousand-plus

undergraduates opt to go Greek, a high number for a private

school, says Andrea Gaspardino (below), director of sorority

and fraternity life. State schools average about ten percent.

“I

think students really want to feel a sense of belonging, to

feel they are part of something bigger,” Gaspardino says.

“Being in a fraternity or sorority helps them to identify

with Emory. They have a bigger place in their hearts for their

organization, and for Emory, because of that experience.” “I

think students really want to feel a sense of belonging, to

feel they are part of something bigger,” Gaspardino says.

“Being in a fraternity or sorority helps them to identify

with Emory. They have a bigger place in their hearts for their

organization, and for Emory, because of that experience.”

“The

overall goal of Campus Life is to promote a sense of community

among our student body, and I think fraternities and sororities

create a sense of several communities within a larger one,”

says John L. Ford, senior vice president and dean of Campus

Life. “I think at large universities like this one, that

bond within a fraternity or sorority often lasts through the

undergraduate experience and beyond into one’s alumni years.”

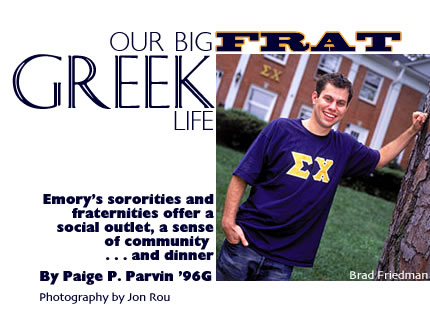

Many

freshmen choose to go through the recruitment process (they

avoid the usual term “rush,” because it is thought

to connote hazing) because of the social networking opportunities

it offers. Brad Friedman (above), a junior from Boca Raton,

Florida, who’s pre-med and also majoring in political science,

said he participated in fraternity recruitment because one of

the leaders in his freshman advisory group was president of

the Inter-Fraternity Council at the time, a position Friedman

holds now.

“He

invited me over to his fraternity house and I met a lot of kids

that way,” Friedman says. “I thought it was cool.

Everyone ate together and seemed to have a great time.”

“Fraternities

add so much to my college experience that I actually cannot

even begin to explain it all,” says Travis Blalock (right),

a senior from Dallas, Georgia, majoring in religion and ethics

and a member of Kappa Alpha. “I live with my brothers,

eat with them, party with them, study with them, and work with

them. My love of Emory has been shaped by the potential growth

and success of the fraternity community, despite the negative

stereotypes fraternities take on.” “Fraternities

add so much to my college experience that I actually cannot

even begin to explain it all,” says Travis Blalock (right),

a senior from Dallas, Georgia, majoring in religion and ethics

and a member of Kappa Alpha. “I live with my brothers,

eat with them, party with them, study with them, and work with

them. My love of Emory has been shaped by the potential growth

and success of the fraternity community, despite the negative

stereotypes fraternities take on.”

For

Emory women, going Greek is a different experience from that

of the men, mainly because the sorority lodges don’t accommodate

more than a couple of residents, and chapter members don’t

take regular meals there. Without more residential housing,

it’s difficult for sororities to provide the same intense

bonding opportunities that come from living under the same roof.

But the lodges offer common spaces for studying, working, meeting,

and just hanging out together.

Despite

the differences, Emory’s nine sororities are thriving,

with the largest chapter numbering 190 members. Of 1,301 freshmen,

452 women went through sorority recruitment this year (as compared

to 312 men), and 401 were placed in chapters (188 men joined

fraternities).

Elise

Hammonds (left), a junior and president of the Inter-Sorority

Council, says being in a sorority “makes Emory smaller.

It’s 160 faces on campus you can know and say hello to.

They’re your sisters and they help you out if you need

it.” Elise

Hammonds (left), a junior and president of the Inter-Sorority

Council, says being in a sorority “makes Emory smaller.

It’s 160 faces on campus you can know and say hello to.

They’re your sisters and they help you out if you need

it.”

“The

Greek system is vital to this campus,” agrees Christopher

Garcia, a senior Sigma Chi from San Diego majoring in business.

“I guess it’s because of the social stuff–the

mixers, date parties, socials. Greeks are always the fun people.”

Of

course, it’s precisely because of the high level of “fun”

associated with Greek life–commonly known to engender alcohol

use and abuse, loud parties, hazing or abuse of new initiates,

destructiveness, and a general propensity to debauchery a la

the 1978 movie Animal House–that the fraternity and sorority

system has become increasingly controversial at American universities,

particularly in the last decade. More often than not, fraternities,

not sororities, make headlines and get the credit for the Greeks’

bad reputation, perhaps because they tend to have bigger houses,

longer histories, more elaborate traditions, and tougher expectations

for their new initiates.

Ongoing

troubles have led some colleges, including Bowdoin College,

Colby College, and Alfred University, to abolish Greeks altogether;

others have severely curtailed their activities. In 2001, Hamilton

College President Eugene Tobin published an opinion in the Chronicle

of Higher Education describing how, after years of struggling

to manage unruly and socially dominant fraternities, Hamilton

finally opted to close their houses, but allow the fraternities

to remain as recognized student organizations. Although he ultimately

declared the move a success, it was met with vehement resistance

from both students and alumni.

Ten

years ago, Emory’s Fraternity Row, too, was on thin ice.

Its chapters were limping along, hobbled by lagging membership

and houses that were in serious disrepair. Worse, the fraternities

were frequently called on the carpet for violating national

policies on alcohol use, recruitment, and new member initiation.

Six of the fourteen chapters were temporarily banned from their

houses in the last decade.

In

the late 1980s, for instance, the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity

was struggling with consistently poor grades. Its members were

also known for high alcohol use, and were repeatedly cited for

hazing.

Paul

McLarty ’65C, an alumnus of the fraternity, says he went

back to visit the house during his twenty-fifth reunion in 1988

and was disturbed by what he found.

“We

were dead last in terms of GPA of all the Greek organizations,”

McLarty says. “The house was just in terrible shape. The

chapter did not have a chapter adviser. They were having hazing

problems.”

The

scene was a far cry from what McLarty remembered of his own

experience as an ATO. “In my house and in most houses,

we had a good leadership structure,” he recalls. “We

were electing our best leaders to head the fraternity, and they

were also likely to be on the honor council or in student government.

When I came back all those years later, the fraternities wanted

the leader to be the biggest party guy. I found that a little

upsetting.”

McLarty,

one of many Emory alumni who have continued to support their

Greek chapters, became the chapter adviser and tried to help

the brotherhood get back on the right track. Despite his efforts,

though, in 1994 an ATO pledge wound up in the hospital with

alcohol poisoning and the fraternity’s charter was terminated

for a year. “We basically had to start all over,”

McLarty says. “We went out and recruited a brand-new group

of young men.”

Other

party violations at Emory include a bash in 1993 where a fraternity

destroyed all the fire alarms in their house, getting themselves

kicked off campus. More recently, all frats were put on probation

after a party with a dangerously high seven-hundred-person guest

list.

Rather

than disbanding fraternities or depriving them of their houses,

Emory administrators resolved to pull them closer. Campus Life

leaders developed the Phoenix Plan, which brought the responsibility

for maintenance and oversight of the fraternity houses under

University governance. Previously, chapter members paid their

housing costs to local fraternity house corporation boards made

up of alumni, who were responsible for maintaining the structures,

with the help of student leaders. Now, says Bridget G. Riordan,

assistant vice president for Campus Life, “The alumni don’t

have to worry about fixing the facility all the time, just about

making a strong chapter.” The University also placed full-time,

paid house directors in each house.

Not

surprisingly, Greek students and alumni had mixed reactions

to the Phoenix Plan. Some strongly objected, saying it compromised

their autonomy. But half a dozen years later, most have come

to accept and even welcome it.

“There

are pluses and minuses,” IFC president Friedman says, “but

there are more pluses. It takes a lot of pressure off individual

house leadership.”

Within

a couple of years of the implementation of the Phoenix Plan

in 1997, all the major maintenance issues had been addressed,

and many of the fraternity houses had been fully refurbished.

Now Fraternity Row boasts impressive, well-kept houses, with

rooms similar to those in dorms. (Certain upgrades, like the

gleaming billiard tables, leather chairs, and portrait of General

Robert E. Lee in the KA house, are still helped along by alumni

funds, although Emory oversees the work.) The students’

housing expenses, which they pay to the University, are about

the same as the cost of living in dorms.

Plans

are being formed to improve the sorority lodges, and will likely

include building new, more residential homes for the sororities

and including them in the Phoenix Plan, according to Riordan.

“I

think we can be proud of the beautiful appearance of Fraternity

Row, and much of that is due to the Phoenix Plan,” says

Ford. “We are able to exert a positive influence on some

potentially problematic aspects of Greek life.”

When

ATO was re-chartered in 1995, their house was renovated under

the Phoenix Plan. The chapter also had some new standards in

place–among them a 3.2 GPA requirement, which altered the

potential pool considerably. In the last six years, McLarty

says, there have been only two semesters when ATO did not have

the top GPA on the row, and they have won the Dean’s Cup

twice. “I think the fraternity is doing very well,”

McLarty says.

The

Phoenix Plan, as hoped, revitalized more than just the houses.

Fraternity membership is up as compared to a decade ago, and

at this point all Emory fraternities are in good standing, says

Riordan, with drinking and hazing policies being taken more

seriously.

Indeed,

Fraternity Row at Emory is considered to have a relatively tame

party scene. A recent editorial in the Emory Wheel actually

urged the University to “make Greek life fun again,”

claiming a new party policy passed in 2002 by the IFC is so

strict it’s stifling Greeks’ social life. Visitors

to the fraternity houses are closely monitored during parties,

and Emory police cars cruise the row to discourage underage

drinking. “While student safety obviously should remain

a top priority,” the Wheel wrote, “ . . . the

Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life needs to make sure it

isn’t so concerned with taming the campus social scene

that it kills it altogether.”

Hazing,

too, is reputed to be mild at Emory. All fraternity and sorority

members are required to sign a strict anti-hazing policy. “Our

school is one of the best in making sure there is no hazing,”

Friedman says. “The hazing policy at this point is so strong,

it’s gotten rid of 90 percent of the problems.”

Emory

administrators have been “extremely pleased,” with

the Phoenix Plan and related developments in the Greek system,

says Riordan. “We believe the students are having a valuable

fraternity experience and also living in a place where they

can have pride. We have been able to serve as a model community

to many other universities.”

Academically,

the average GPA of members is higher than the average of the

University as a whole, according to Riordan–not the case

at many universities. Most Emory fraternities and sororities

have a minimum GPA requirement of at least 2.7 for membership.

Many have study groups, and in the fraternity houses there are

designated upperclassmen halls where serious studying is expected.

ISC

president Hammonds chose not to pledge a sorority during her

freshman year because she was concerned about how the commitment

would affect her grades. But since she joined Kappa Kappa Gamma

in her sophomore year, she says, her GPA has actually gone up.

“If anything, the chapter has encouraged me to improve

my grades,” Hammonds says. “If I’m having trouble

with the class, there’s always someone who has taken it.”

During

the fall semester, Greek students also put in 1,900 community

service hours and more than five thousand philanthropy hours

total, raising more than $30,000 for various charities, according

to Gaspardino. Each organization works with particular philanthropies

on projects throughout the school year, many of which are selected

or encouraged by their national leadership. There are also all-campus

events such as Greek Weekend, when sororities and fraternities

join forces to raise money for various charities–and enjoy

some friendly competition.

“A

lot of our sisters are already involved in some kind of volunteer

work when they join,” Hammonds says. “We take this

very seriously.”

All

Greeks participate in philanthropy to some extent, but the historically

African-American fraternities and sororities place special emphasis

on their service work. Senior religion major Alicia Goldsby,

a former ISC president and member of Delta Sigma Theta, one

of Emory’s two black sororities, says public service is

the main focus of their tight-knit, seventeen-member chapter.

They hold programs devoted to educational development, international

awareness, economic development, physical and mental health,

and political awareness. Although they do hold social events,

the Deltas don’t host parties with alcohol or have “date

parties.”

“Membership

in the Greek community has afforded me the opportunity to hold

leadership positions in my chapter and on campus, and to meet

people I would not have met otherwise,” Goldsby says. “If

you are interested in service, then it’s advantageous to

join a black sorority; if not, you can find another chapter

that fits you.”

More

than just a social sisterhood, the black sororities were founded

in part to help African-American students become successful

women on all fronts. Most members stay active and involved long

after college, taking advantage of their national chapter’s

educational, social, and career networking opportunities. The

intense, lasting commitment and serious attitude are a hallmark

of most historically black Greek organizations.

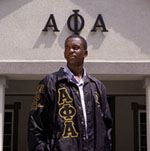

Stanley

Taylor, a senior political science major and president of Alpha

Phi Alpha, one of three black fraternities, says he became interested

in joining while still in high school, when he spent summers

volunteering in a program for low-income youth in his hometown,

New Orleans. Each summer there would be just a few black men

who volunteered (most of the volunteers were women), and as

it happened, all the college men were members of APhiA. Stanley

Taylor, a senior political science major and president of Alpha

Phi Alpha, one of three black fraternities, says he became interested

in joining while still in high school, when he spent summers

volunteering in a program for low-income youth in his hometown,

New Orleans. Each summer there would be just a few black men

who volunteered (most of the volunteers were women), and as

it happened, all the college men were members of APhiA.

“Something

about the way they carried themselves, and the way they gave

back to that program, definitely piqued my interest,” Taylor

says. “I wanted to find out what it was all about.”

The

Alphas’ largest annual philanthropic event is the Step

for Sickle Cell, one of the most profitable fund-raisers at

Emory. The fraternity has raised more than $65,000 for the Sickle

Cell Foundation of Georgia. The seventeen-member chapter and

its alumni also work with Big Brothers Big Sisters, and volunteer

at Wesley Woods Geriatric Center in partnership with their graduate

chapter.

“I

think when the historically black organizations were started,

it was a time when African Americans were really in a struggle,”

he says. “The purpose was to aid those students who were

really a minority on campus, to help them be successful and

aid others. That focus on community service and uplifting the

community is essential to the founding of APhiA.”

“Historically”

African American means the black Greek organizations are not

exclusively black; the Emory APhiA chapter has included white,

Asian, and Indian members. Likewise, the mainstream fraternities

and sororities include a growing number of minority members.

Two recent ISC presidents have been African American.

“No

one at Emory recruits based on race. It’s just not done,”

Friedman says.

It’s

true that most Emory fraternities and sororities are considered

more racially inclusive than some of the well-established organizations

at large Southern schools, many of which have all-white chapters.

The University of Alabama, for instance, came under fire in

2001 when a promising African-American woman rushed the white

sororities and did not receive a single bid.

But

Emory has had its own, albeit limited, clashes with Southern

racial tensions. In 1998, an Emory student, reportedly not a

member of the fraternity but a guest, was photographed wearing

blackface at a Kappa Alpha Halloween party. The picture appeared

in the 1999 yearbook, angering some black students. The incident

was resolved through the Office of Student Conduct, Riordan

says.

“Anytime

we have an accusation of non-inclusiveness, we look at it very

seriously,” Riordan says. “I would guess we probably

have one of the most diverse Greek systems anywhere.”

Even

so, diversity is an area where some, including Dean Ford, feel

Emory’s Greek community could improve.

“Greek

life is an effective way to create a sense of community, but

the extent to which we can use it to help students from different

backgrounds–racial, ethnic, or religious–to become

a part of the same fraternity or sorority–it would be an

important measure of our success if we could do more of that,”

Ford says.

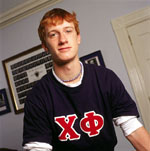

Greek

organizations at many colleges are also notoriously unfriendly

to gay students, with few or no openly gay members. Both Friedman

and Chi Phi President Louis Graff (left), who hold leadership

positions among Emory fraternities, say that a student’s

sexual orientation is “not a problem,” and that there

are openly gay men on Fraternity Row. But a recent editorial

in the Emory Wheel suggests that anti-gay bias may still

lurk under the surface. Gay 2003 graduate Mikiel Davids wrote

to praise her own sorority for hosting a Speakers Bureau from

the Office of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Life,

but added that all Greeks should take a look at the climate

they create around issues of sexual orientation. Greek

organizations at many colleges are also notoriously unfriendly

to gay students, with few or no openly gay members. Both Friedman

and Chi Phi President Louis Graff (left), who hold leadership

positions among Emory fraternities, say that a student’s

sexual orientation is “not a problem,” and that there

are openly gay men on Fraternity Row. But a recent editorial

in the Emory Wheel suggests that anti-gay bias may still

lurk under the surface. Gay 2003 graduate Mikiel Davids wrote

to praise her own sorority for hosting a Speakers Bureau from

the Office of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Life,

but added that all Greeks should take a look at the climate

they create around issues of sexual orientation.

“Running

from the existence of homosexuality in Greek life not only makes

houses that do so hypocritical, but threatens the justification

for their existence,” she wrote. “These houses generally

proclaim to provide an unconditional support system that members

can rely on . . . However, brothers or sisters [cannot] truly

come to know each other deeply if individuals feel they cannot

openly and honestly express themselves.”

Some

seventy percent of Emory students opt not to be a part of Greek

life. Anton DiSclafani ’03C (right), class speaker at this

year's Commencement, says she decided against pledging a sorority,

although she does not have strong feelings against Greek students

or the system as a whole. Some

seventy percent of Emory students opt not to be a part of Greek

life. Anton DiSclafani ’03C (right), class speaker at this

year's Commencement, says she decided against pledging a sorority,

although she does not have strong feelings against Greek students

or the system as a whole.

DiSclafani

does have close friends who are in sororities, but she says

other friends, particularly those who are more artistically

or intellectually inclined–the “alternative”

crowd–shun Greeks altogether.

“I

guess I just decided pretty early on that a sorority was not

for me,” DiSclafani says. “I didn’t have anything

against them, but I didn’t see myself belonging to such

a group. Nobody in my family has ever belonged to a sorority.

I understand that it’s a social outlet, but I like the

idea of creating my own social avenues instead of depending

on a group. The problem with the Greek system, if there is a

problem, is that it gathers people who are similar anyway.”

Despite

these concerns, Greeks at Emory generally have a reputation

for offering a much more open, welcoming social network than

those at many other schools. Most Greeks say that while some

of their close friends are in their fraternity or sorority,

they also have many friends outside their chapter.

Adam

Teeter, a junior from Auburn and president of the Student Programming

Council, says he grew up near Auburn University, where the Greek

system is much more socially influential and exclusive than

at Emory. Teeter opted not to pledge a fraternity because he

says he didn’t want to limit himself socially, but by comparison,

he says, the Greek climate at Emory is much more relaxed. Adam

Teeter, a junior from Auburn and president of the Student Programming

Council, says he grew up near Auburn University, where the Greek

system is much more socially influential and exclusive than

at Emory. Teeter opted not to pledge a fraternity because he

says he didn’t want to limit himself socially, but by comparison,

he says, the Greek climate at Emory is much more relaxed.

“At

Auburn, it’s like, you only go to your own frat parties,”

he says. “At Emory I see Greek kids at every party, every

campus function. The houses are a lot more diverse and welcoming.”

Teeter

says Greeks at Emory make a more positive contribution to the

campus than they do at many other institutions, but from his

perspective in student programming–which brings band parties,

speakers, and a variety of social opportunities to campus–he

wishes they carried an even greater presence at all-school events.

“We

would appreciate it if the Greeks would show more school spirit,

be out and take part more,” he says. “Because school

spirit is so low, Greek life could be something that could really

create a positive change.”

Like Greeks at most schools, fraternities and sororities at

Emory seem likely to remain the subject of continuous, low-grade

controversy–but they seem equally likely to remain a robust

presence on campus, and an engaging, supportive community for

those who join them.

“People

in fraternities tend to be happier,” says senior Louis

Graff, Chi Phi president, one evening as he checks in on a couple

of sophomores hanging out in their room on the lower hall. They’re

doing homework at their desks underneath a sleeping loft; they

look up and wave. “Emory is much more palatable when you

have this smaller group of guys to turn to. The fraternity is

the thing that really keeps kids connected to campus.”

And

then Graff has to go. It’s dinnertime.

|

|

| |

©

2003 Emory University

|