JIM

WAGNER

wants Emory to be a household name.

His

intention to help make it so was among Wagner’s first pledges

to his new community when he was named the University’s

nineteenth president July 30.

Emory

needs a crisp, refined vision, Wagner says, to become nationally

recognized as an “inquiry-based, values-guided educational

institution of the highest order.”

“Emory

is too good not to be recognized as a leader,” he told

those gathered at a press conference announcing his appointment.

“The excitement here is not only about what Emory is, but

what it can be.”

Wagner

came to Emory September 2 from Case

Western Reserve University in Cleveland, where he had been

provost and vice president since 2000 and also served for fifteen

months as interim president. Wagner was tapped by Emory’s

presidential search committee to succeed President

William M. Chace after an eight-month national search in

which some 150 candidates were reviewed, fifteen were personally

interviewed, and four were considered finalists.

But

in the end, the committee’s decision was unanimous.

“This

is someone who understands higher education, who understands

the uniqueness of Emory’s heritage and the role Emory can

play, who is very ambitious for Emory to achieve its potential,

and who has got the ability, energy, and ambition to take it

there,” says Ben F. Johnson III, chair of the Board of

Trustees and of the search committee. “I have never been

more convinced of anything in my life than Jim Wagner being

the best possible president Emory could have in the years going

forward.”

Prior

to his selection, James W. Wagner was not a household name at

Emory. To a university whose past two presidents have been a

theologian and a scholar of Irish literature, Wagner brings

a background in engineering and materials science. He holds

a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from the

University of Delaware and a master’s in clinical engineering

and Ph.D. in materials science from Johns Hopkins University.

Before his arrival at Case Western Reserve, Wagner spent thirteen

years on the engineering faculty of Hopkins, where he was chairman

of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering for four

years and held a joint appointment in the Department of Biomedical

Engineering. At Case Western Reserve, he served as dean of the

School of Engineering for two years before becoming provost.

“I

must admit, I was a little taken aback when I saw his [curriculum

vitae],” says David Lynn, Asa Griggs Candler Professor

of Chemistry and Biology and a member of the faculty advisory

committee, which helped guide the search committee. “But

he clearly has a vision and does understand what it means to

be a liberal arts institution. He is a very articulate, well-reasoned

person, very likeable and engaging. And he had really done his

homework on Emory, what it is, its strengths and weaknesses.

He had thought very carefully about what kinds of things he

could bring to the institution.”

Emory

scholars in the humanities fields have ventured careful optimism

and a willingness to keep an open mind about Wagner’s commitment

to the liberal arts.

“To

be a truly great university demands a wide spectrum of intellectual

activity, and the liberal arts in particular have traditionally

been the basis for most of the best research universities,”

says Martine Watson-Brownley, director of Emory’s Center

for Humanistic Inquiry. “Everything I have read and seen

of President Wagner indicates that he understands this, and

I am not worried that the humanities will be overlooked under

his leadership.”

How

does Wagner believe his past experience will suit Emory’s

institutional culture?

“Very

well,” he says, briskly. “It’s funny, Ben Johnson

was reflecting on this, and he leaned back in his chair and

said, ‘Well, I guess everybody’s gotta come from somewhere.’

I would like to think the engineering background is foundational,

but it doesn’t define or restrict who I am or what I can

contribute in leadership. In fact, maybe in some ways it puts

a slightly different spin on it that will be constructively

provocative for where the institution needs to go and what kind

of leadership it could benefit from. Vocationally, having been

called to serve as provost and also as an interim president

of a comprehensive university, one of the great recent joys

of my career has been to work hard to understand scholarship

in areas outside of the sciences and engineering.

“The

successful imprint on a student who has enjoyed a liberal education

is that they have done two things,” Wagner adds. “They

have mastered a certain discipline for learning, and they’ve

developed a continuing hunger for more knowledge, greater discovery.

I would hope that my engineering background has done that for

me.”

Wagner’s

enthusiasm for engineering stretches back to his boyhood in

Silver Spring, Maryland, when he was frequently found hunkered

down over various “gadgeteering” projects: he built

a canoe, a small sailboat, a go-cart, a sled, and a whole fleet

of model airplanes before he was old enough to drive. His partner

on almost all those ventures was his dad, a lifelong mentor

whom Wagner calls “an unusually wise person” and who

summoned patience when his son scattered tools around the garage.

On vacations together, the two still tinker with old cars, including

a replica of a 1929 Mercedes they built from a kit. Wagner’s

parents, Bob and Bernice Wagner, live in Stone Mountain, near

Atlanta.

Wagner

says he didn’t enjoy school much as a kid, although it

did tap into his natural curiosity about how things work. He

recalls a high school science project for which he bought a

series of fertilized eggs and tried to cut windows in the shells

to watch the embryos grow. But overall, he didn’t take

well to the separateness of school and home life.

“I

wanted to answer a vocation where my life would not be so segmented,”

he says. “Growing up, it was school and not school. I didn’t

want it to become work and not work. I wanted to find, truly,

a vocation and not an occupation, where you love your work and

expect it to love you and your family back, where everything

you do is part of a continuum.”

This

desire to create a seamless life of the mind and heart may be

why Wagner’s devotion to his work is well known.

“One

of his foremost work characteristics is incredible dedication,”

says Lynn Singer, deputy provost and professor of pediatrics

at Case Western Reserve, who served as interim provost when

Wagner was interim president. “He answers every e-mail,

he’s very involved with students. Jim is one of those people

who really just seems to enjoy almost everything he does, every

meeting, every new engagement. He genuinely gets into the moment.

And he always seems to be the last person out of the university

each evening.”

One

of those evenings, Singer recalled, Wagner left with her favorite

umbrella, which had broken and wound up in the trash. He brought

it in the next morning, repaired and good as new. “I guess

that’s the engineer in him,” Singer said.

His

commitment may also be why Wagner, at fifty, has enjoyed a fast

climb to the upper ranks of university administration, from

dean to provost, interim president to Emory president, in the

last five years.

“Why

can’t I hold a job?” he quips. “My kids ask the

same thing. It has been a real fast-track, intensive learning

period, and there are up and down sides to that. But every time

[you approach a new challenge], there is a right level of butterflies

you’re supposed to have if you’re going to be at the

edge to do this job right. I have experienced the butterflies

a few more times, perhaps, in recent memory, and I’ll tell

you that that unrealized potential, the anticipation of growing

in potential with each position, is something I bring to Emory

and I look forward to experiencing as Emory and I grow together.

I am expecting this job to be my best. I don’t know that

I have ever been as excited as I am right now.”

If

the Emory presidency indeed brings out Wagner’s best, the

University community has much to look forward to, according

to his former colleagues. They sing his praises unbidden and

without exception. Wagner’s leadership style is described

as at once responsive and decisive, visionary and thorough,

introspective and inspiring, accessible and authoritative.

“Jim

knows how to be a leader, but he treats everyone as if they

have something to contribute,” Singer says. “He’s

fun, dynamic, engaging, and respectful, and he really creates

an atmosphere of cooperation. I think what I will miss the most

is the dynamic interaction, the fun work environment he creates.

But I had to chuckle when I learned he was going to Emory, because

he drinks Coca-Cola Classic every day at lunch. There must be

some destiny at work there.”

At

Case Western Reserve, Wagner was apparently popular with everyone

from lone-wolf laboratory researchers to wide-eyed freshmen.

He became known for his ability to pay equally appropriate attention

to such disparate matters as undergraduate life, technology

infrastructure, diversity initiatives, faculty benefits, and

fund raising.

Key

initiatives that Wagner led at Case Western Reserve include

the establishment of a commission to enhance undergraduate education

and student life, which addressed academic curriculum revision

in addition to student services and resources. Despite his own

academic career in high-level graduate research, he proved a

champion of the undergraduate students.

“He

wanted to understand the students’ perspective, to know

what students thought,” says Samir Korkor, a Case Western

Reserve student who started a faculty-student program called

“Building Bridges” with Wagner’s help. “He

was always willing to listen to students. He was very much a

mentor to me. He wasn’t the kind of person who did his

job just to do it. He did it with this unique, incredible motivation,

and profound appreciation, and passion. He does things with

passion.”

While

interim president at Case Western Reserve, Wagner also oversaw

the improvement and restructuring of the university’s technology

transfer operations and created the Postdoctoral Researchers

Association. He helped complete a campus master plan, planned

for a capital campaign, and formed a presidential advisory committee

of staff, faculty and students on women and minorities in the

university.

“In

terms of him being responsive to staff, I don’t think you

could have found anyone better,” says Kathryn Howard, a

research assistant and chair of Case Western Reserve’s

Staff Advisory Council. “He’s approachable, bright,

and dedicated. You found yourself a gem in Jim Wagner. Gems

usually are not polished, but this one is polished.”

Wagner

also led the development of BioPark, a joint venture of Case

Western Reserve, University Hospitals, and the Cleveland Clinic.

Such institutional collaboration and relationship building,

particularly in the area of health sciences, is a talent many

hope to see him bring to Emory.

“Jim

is a man of vision and energy who can lead Emory to elite status

as a leading research university,” says Thomas Lawley,

dean of Emory’s School of Medicine. “He is an engineer

who will help foster deeper and stronger ties with Georgia Tech

and create opportunities that are additive to those in biomedical

engineering.”

“We

are all really looking forward to working with Jim Wagner,”

says Don Giddens, dean of the School of Engineering at the Georgia

Institute of Technology, who worked closely with Wagner as a

dean at Johns Hopkins and also was the architect of the joint

biomedical engineering program between Emory and Georgia Tech.

“There is a natural alliance already established between

Emory and Georgia Tech, and Jim will be very interested in how

we can build on that, how we can leverage each other’s

strengths and be complementary. There’s a lot the two institutions

can do together.

“At

the sort of big-picture level, Jim has a characteristic of being

able to define a vision for an organization. He has a drive

for excellence and his style is very collaborative. He listens,

takes in information, but then is able to move forward in very

clear-cut ways.”

So

far, Wagner shows no signs of being any less admired at Emory

than he was at Case Western Reserve. Already he has promised

continued support for many of the initiatives at the heart of

Emory’s institutional philosophy and image: commitment

to preserving the environment, which was a special priority

for President Chace; diversity efforts, including progressive

policies on sexual orientation; and the cultivation of valuable

ties with organizations such as The Carter Center. Wagner has

favorably impressed Emory community members across campus and

beyond with his ability to both articulate the University’s

strengths and identify its shortfalls.

One

reason Emory is not a household name, he says, is that we don’t

know what we have.

“Leadership

is a lot about ideas and drawing ideas from people,“ Wagner

says. “One of the first jobs of the new president will

be to hold up an enormous mirror to the faculty, a clean mirror,

and help them recognize who they really are, the power they

have.”

Wagner

has said one of his early priorities as president will be to

begin shaping a clearer vision for what Emory is, its resources

and gifts, and to better define the position it might hold among

the nation’s best schools. As well as being a top-notch

research university, Emory is marked by a conscious morality,

Wagner notes. The emphasis on values, ethics, and service to

the common good that characterized the leadership of President

James T. Laney and was built upon by Chace makes Emory a remarkable

place.

“Emory

is in a special position,” Wagner says. “It has the

opportunity to be known and to be recognized for being inquiry-based

and values-guided. Inquiry-based, of course, is making reference

to the fact that the University is a research university, and

in everything it does, that should permeate its activities.

As to the second part, there is an ease with which a vocabulary

of values is used on this campus; it’s discernible even

on a casual visit.”

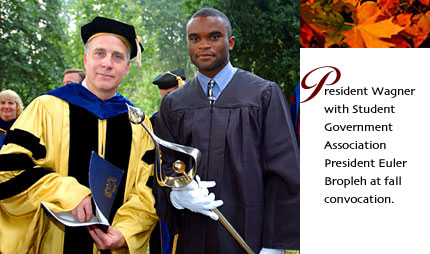

Wagner

has worked hard to immerse himself in Emory’s culture,

to learn the place from the inside out. On visits to the campus

throughout the summer and early fall, he has shaken many dozens

of hands and begun at least as many conversations, including

at an open community appearance outside the Dobbs University

Center after his presidency was announced. At President Chace’s

invitation, he also presided over the opening convocations at

Emory and Oxford College when school began this fall.

He

will spend the fall semester living in an apartment at the Clairmont

Campus while deferred maintenance takes place at Lullwater,

the presidential residence. Wagner’s wife, Debbie, will

remain in Cleveland this academic year while their younger daughter,

Christine, finishes her senior year in high school, and their

older daughter, Kimberly, returns to Miami University in Ohio.

For a time, the Wagners plan to become very familiar with the

inside of airplanes.

One

of Wagner’s scheduled visits to Emory had to be postponed

when much of the northeast, including Cleveland, lost power

for hours one afternoon in August. The blackout left Case Western

Reserve without running water and Wagner grounded. Speaking

from his office there, where he spent the day on conference

calls instead of on the Emory campus, Wagner seemed to be taking

it all in stride.

“It’s

been interesting and awesome, in a sense, to realize how fragile

we are,” he said. “And also awesome, without all the

lights, to see the Milky Way, which hasn’t been seen in

this town in many years.”

This

is Emory’s new president: an engineer who can understand

precisely why the lights went out, and, at the same time, look

up and admire the Milky Way. And anticipate the future with

just the right level of butterflies.