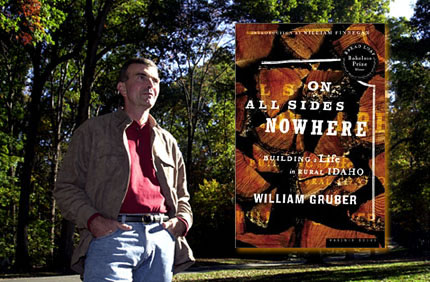

Professor

and chair of the Department of English William Gruber received

the 2001

Katherine Bakeless Nason Prize for creative nonfiction from

the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference at Middlebury College

for his collection of essays, On All Sides Nowhere: Building

a Life in Rural Idaho. As part of the prize, Gruber attended

Bread Loaf in August 2002. Below is an excerpt from On All

Sides Nowhere. For additional information, read about Gruber

in Emory

Report.

“Idaho

first registered on my consciousness at the movies. In the summer

of 1960 I was sixteen, and in the middle of August of 1960 there

was no place in suburban Pennsylvania to find air conditioning

except in supermarkets or theaters. I could not spend summer

days amidst the cabbages and canned goods, and so to escape

the heat I went with my friends as often as I could to the movies;

one of the movies I sought out in August of 1960 was an elegy

for the waning days of modern civilization, On the Beach.

To

the filmgoing public in 1960, keenly aware that despite all

the best intentions the cold war could suddenly turn hot, the

movie was perfectly credible. It was set only a few years into

the future; a calendar on the wall read, ominously, “1964.”

Nuclear war of undisclosed origins had killed everyone in the

northern hemisphere, and now, as a lethal cloud of radiation

spread slowly over the planet, one of the last surviving groups

of humans clustered in Melbourne, Australia, to await the end.

It was an intoxicating, almost carnivalesque, experience; Gregory

Peck played the romantic lead opposite Ava Gardner, and at one

point in the film, Peck, the taciturn commander of a nuclear

submarine, tells Ava Gardner about his origins. In answer to

her question about his childhood home, he replies with a single

word that at the time seemed more homiletic than informative:

“Idaho.”

Whose

decision was it for Peck to claim Idaho for his birthplace?

Of all the possible states the script writer could have chosen,

why that one? And it was a choice: for the record, Peck was

born in La Jolla, California, and his character in Nevil Shute’s

novel from which the movie was adapted comes from Westport,

Connecticut. Peck’s “Idaho” drops like a stone

into a well of unknown depth; it falls without trace, without

echo. It is a piece, apparently, of purely gratuitous information.

Why

Idaho? The name resonates oddly with Melbourne and San Francisco,

the environments of On the Beach. Those places set the

mood of the film. To Americans in 1960, Melbourne was alien,

exotic, and San Francisco brought to mind the glitz and romance

of California. Set in that context, and set against the despairing

hedonism of humans who number their remaining days according

to the drifting global winds, “Idaho” seems dissonant.

Its sound is stark, but as Peck speaks it it sounds also moral

and attractive. It seems to express Peck’s loneliness,

his longing for the purity of childhood and for the innocence

of a world before the Bomb. None of the familiar mythic names

of the American West, not Texas or Oregon or Colorado, would

have the same aura of pure expressivity. My guess is that the

name “Idaho” was chosen for its semantic emptiness.

The name made sense because to most people Idaho” meant

nothing, and, meaning nothing, it could stand in for the infinite

pathos of a world that would shortly cease to exist. Idaho was

then, and in some ways still is, a geographic What You Will,

and as a result the name “Idaho” becomes a kind of

cultural Rorschach test for whoever happens to reflect on it.”

|

|