Winter 2011: Features

Chair Amy Gutmann of Penn and Vice Chair James Wagner lead discussions on synthetic biology at the November meeting of the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues in Atlanta.

Ann Borden

From Lab to Life

When President Barack Obama seeks advice on the potential benefits—and risks—of biotechnology, he consults a special commission vice chaired by Emory President James Wagner

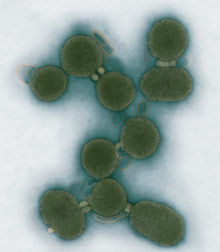

The first self-replicating synthetic bacterial cell, nicknamed “Synthia,” manufactured at the J. Craig Venter Institute; the lab announced in May that it had created a new species.

Venter Lab

Related Story

By Mary J. Loftus

In almost any field—science, law, business, politics, medicine—the very skills, ingenuity, and technologies that promise tremendous benefit to society can also bring grievous harm. But perhaps nowhere is this so true as in the emerging area of biotechnology.

Breakthroughs in genetic engineering, nanotechnology, and synthetic biology are occurring at a dizzying pace. And with these advances comes the potential to create artificial fuels and artificial pathogens, microscopic medical markers and microscopic weapons, synthetic vaccines and synthetic pandemics.

“As our nation invests in science and innovation and pursues advances in biomedical research and health care, it’s imperative that we do so in a responsible manner,” President Obama said last year, announcing the creation of a new Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues.

Obama appointed as chair Amy Gutmann, president of the University of Pennsylvania, a political philosopher and scholar of ethics and public policy.

And he selected Emory President James Wagner as vice chair, attracted by his background as an engineer with specialties in electrical, materials science, and biomedical engineering, as well as the fact that he has championed ethical engagement as a vital part of Emory’s identity. Universities, Wagner believes, must produce the next generation of ethical professionals.

“Training a mind alone can be dangerous, if this is decoupled from moral guidance,” he says. “We need people who feel confident in their ability to exercise judgment based on ethics and to make decisions based on moral principle.”

The remaining eleven panel members are scientists, ethicists, public policy experts, and MD/PhDs—one of whom is a Franciscan friar.

Lightning-rod issues ignite

When the commission met in Atlanta in November, Gutmann and Wagner took the opportunity to hold an evening dialogue on bioethics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Wagner told the audience—mostly Emory and Penn alumni—that universities must be able to take up “lightning-rod topics,” such as the use of embryonic stem cells to treat chronic diseases.

“It’s not that we are aggravatingly neutral, although sometimes we are,” he said. “We must be inclusive. And it’s not about tolerating diverse viewpoints, it’s about demanding that we have people who represent as many viewpoints as possible.”

No topic was off limits during the wide-ranging discussion, moderated by Kathy Kinlaw 79C 85T, associate director of the Emory Center for Ethics, and Penn’s Jonathan Moreno, a professor of medical ethics and the history and sociology of science.

“The devil and God are both in the details,” Gutmann said of the difficult decisions sure to arise in bioethics. Should “designer” genes receive patents? How can lifesaving vaccines be fairly allocated? Can biotechnology be controlled, or will its creations run amok?

By now, Gutmann and Wagner are well practiced at bioethical hairsplitting and at entertaining possible future scenarios both inspiring and alarming (although Gutmann joked that The Blob is “the only movie I ever walked out of”).

They have led three public commission meetings, the third of which took place November 16 and 17 at the Emory Conference Center Hotel. They’ve listened to dozens of experts speak about the potential good works of biotechnology (organisms that can gobble up oil spills) and terrifying misuses (artificial germ warfare).

They’ve considered the impact of biotech research being conducted by professional scientists in labs and amateur or DIYs (“do-it-yourselfers”) in basements and garages.

And in mid-December—just a month after the Atlanta meeting where final details were debated—the commission came up with a list of recommendations for how the government should respond to a startling scientific development in synthetic biology: the possible creation of life.

The storm over Synthia

On May 20, 2010, the J. Craig Venter Institute in Rockville, Maryland, announced that it had created “the first self-replicating species we’ve had on the planet whose parent is a computer.”

The Venter lab’s synthetic single-celled organism, nicknamed “Synthia,” was manufactured from artificial DNA the scientists purchased on the Internet. They then transferred the synthetic DNA into an empty bacterium and allowed it to multiply.

The event made headlines around the world: “Scientist accused of playing God by making designer microbe from scratch,” “Synthetic life breakthrough could be worth over a trillion dollars,” and “Genesis Redux.”

“In the end,” read a piece in the Economist, “there was no castle, no thunderstorm, and definitely no hunchbacked cackling lab assistant. Nevertheless, Craig Venter . . . and colleagues have done for real what Mary Shelley merely imagined.”

Some said Venter had not created life but only “mimicked” it; doomsayers called the organism a “microscopic Frankenstein’s monster.”

The White House was concerned enough to send Gutmann a letter dated the day of the announcement, asking her to set aside all other commission work to make recommendations within six months for how the government should respond to this leap in synthetic biology.

“For the first time, all of the natural genetic material in a bacterial cell has been replaced with a synthetic set of genes,” said the letter, signed by President Obama. “This development raises the prospect of important benefits, such as the ability to accelerate vaccine development. At the same time, it raises genuine concerns.”

During the course of its next three meetings, Gutmann responded, the commission would “examine the implications of the emerging science of synthetic biology, including the announcement in May of the successful creation of a self-replicating bacterial cell with a completely synthetically replicated genome . . . [and] offer recommendations to ensure that America reaps the benefits of this developing field within appropriate ethical boundaries.”

Preparing for the best—and worst

At its first public meeting July 8 and 9 in D.C., the commission invited several experts to talk about the scope and definition of synthetic biology, including Paul Root Wolpe, director of the Emory Center for Ethics, and J. Craig Venter, the father of “Synthia” himself.

“I think this is an area [in which] we are limited more by our imaginations now than by any technological limitations,” Venter told the commission, just hours after its members were sworn in. “I think having an intelligent ethical legal framework for this new science to emerge in is absolutely critical.”

Venter said advances in synthetic biology could lead, fairly quickly, to synthetic flu vaccines and bio-crude fuels, two products his lab is working on through partnerships with Novartis and ExxonMobil.

The next day, Wolpe shared his understanding of various religious perspectives on synthetic biology.

“I spoke to people from a variety of faith traditions, from Buddhism and Emory’s wonderful Emory-Tibet program; people from Islam, Christianity and Judaism, Hinduism,” he said. “What I discovered was that, fundamentally, their objections or their concerns were those of all of us in this room. What are the potential harms? What might happen if these things are released into the environment? They expressed a concern that synbio keep its eye on maximizing human good and reducing suffering, and if it does that, it’s acceptable. That was reflected in the Vatican’s response, I think, where they said the recent creation of Venter’s cell can be a positive development if correctly used. And then there was a warning afterward, that scientists should be careful about playing God, creating life, remembering that only God can do that.”

Modern science and the bioethical dilemmas it poses, Wolpe said, are simply “our newest means of trying to struggle with eternal questions about what our proper relationship is to the natural world, what are the important problems we as a species must solve, and so on.”

Wolpe warned that no matter how thoughtfully and deliberately we as a society proceed, however, there are no guarantees: “We can follow a path where every step is examined individually and found to be ethically unobjectionable and yet, a hundred steps later, we find ourselves in a place that no one wants to be.”

The second public meeting was hosted by Penn in Philadelphia on September 13 and 14, and included an overview of emerging technologies in synthetic biology, a continued look at philosophical and theological perspectives, social responsibility and risk assessment, knowledge sharing, and translating research for the public good.

Renowned bioethicist Arthur Caplan, director of Penn’s Center for Bioethics, cautioned that consequences are hard to foresee.

“We are talking about this against a backdrop where we have had failures in controlling the dissemination of organisms, and I don’t have to remind this group about the problems we’ve had with things getting into places we don’t want them, whether they’re kudzu or Japanese beetles or starlings or, for that matter, zebra mussels and little beetles.”

At its third meeting in Atlanta, the group hammered out eighteen draft recommendations on federal oversight to present to President Obama before the year’s end.

Wagner, addressing his fellow panelists, set forth a series of provocative questions. What if a synthetic biology creation “is more robust than what is in nature?” he asked. “Or what if it could be applied for malevolent purposes? [To] what degree do we interfere with the natural order of life?

“Certainly some risk now can’t be imaginable,” he said, “but our job is to give advice to society on how to be best prepared.’’

Checking the moral compass

On December 16, the commission released its recommendations, New Directions: The Ethics of Synthetic Biology and Emerging Technologies.

“What [we] found is that the Venter Institute’s research and synthetic biology are in the early stages of a new direction in a long continuum of research in biology and genetics,” it states. “The announcement last May, although extraordinary in many ways, does not amount to creating life as either a scientific or a moral matter . . . the likelihood of which still remains remote for the foreseeable future.”

More realistic, says the commission, is the expectation that synthetic biology will lead to new products for clean energy, pollution control, customized vaccines, targeted medicines, and hardy crops.

While forming its recommendations, the commission kept in mind five ethical principles relevant to considering the social implications of emerging technologies: public beneficence, responsible stewardship, intellectual freedom and responsibility, democratic deliberation, and justice and fairness.

What follows is a sampling of the commission’s eighteen recommendations, which can be found in full at www.bioethics.gov.

• Innovation Through Sharing. Synthetic biology is at a very early stage of development, and innovation should be encouraged.

• Monitoring, Containment, and Control. At this early stage of development, the potential for harm through the inadvertent environmental release of organisms or other bioactive materials produced by synthetic biology requires safeguards and monitoring . . . . For example, “suicide genes” or other types of self-destruction triggers could be considered in order to place a limit on their life spans.

• Ethics Education. Because synthetic biology and related research cross traditional disciplinary boundaries, ethics education similar or superior to the training required today in the medical and clinical research communities should be developed and required.

The commission concluded that it had not found cause for immediate concern: “All the experts who testified agreed that any danger is far off in the future. But that is not to say that dangers won’t ever happen. That’s why the commission has opted for a moderate course. It is operating on the principle of ‘prudent vigilance.’ ”

As for the work of Gutmann, Wagner, and the rest of the bioethics panel? They will begin two new projects—one involving the ethics of genetic and neurological testing, the other reviewing human subject trials to ensure that all participants are protected from harm and unethical treatment.

In other words, no rest for the ethicists.